MiXtopia

This article is an attempt to think about a transnational and translational methodology to explore crossroads (X) in what may be called the Transpacific sites of decolonial possibility beyond state borders, sites that are neither American nor Asian, but that constitute a third space. I use the term miXtopia in relation to such sites, a concept that I apply in relation to performance art that portrays life as an act of performing. “Art/life,” a sub-genre of performance, began in the 1960s, experiencing its heyday during the 1980s and 1990s. It was an art form that explored the criss-crossings of art and life through performances that pushed the conceptual limits between forms, blurring and obscuring the borders between them. Expressions that combine two terms, such as “art/life,” “living art,” and the terms “artlike art” and “lifelike art,” conceived by American pioneer performance artist, Allan Kaprow, express a way of life through the medium of art (see Montano 2000). As the conceptual background of this article, I identify subtle yet profound differences between these two terms. While “artlike art” “looks for the meaning of art,” “lifelike art plays somewhere in and between attention to physical process and attention to interpretation” (Kaprow and Kelley 2003: 232, 241). My use of life/art and art/life as “lifelike art” follows on from questions posed by Kaprow: “Is playing at life, life? Is playing at life, ‘life’? Is ‘life’ just another way of life? … Am I playing with words and asking real-life questions?” (Kaprow and Kelley 2003: 240). The imperative for me is to investigate the function of art when it has crossed into “life.” Here lies the in-between, the possibility and the performativity of language that I illuminate in this article. Employing miXtopia as both theory and methodology, I resituate aspects of Okinawan life under Japan’s cultural domination and America’s military occupation, considering the presence of decolonial performance life/art. On another level, miXtopia is similar to the surrealist modality of “le merveilleux” – the marvelous – which signified to them a gleeful freedom of the imagination, a general liberation and purification within an acceptance of material reality, and a capacity for childlike wonder and fresh response” (Sandrow 1972: 19). Here, I deploy X as a playground of “art/life as one continuing space” (Sandrow 1972: 42) where the mundane crosses into the marvelous, transgressing the boundaries between them. Blurring the distinction between art and life, fiction and truth, mind and body, reality and the spiritual, and ideological thought and action in the surrealistic space of the art/life crossroads, life turns from the mundane into the marvelous in critical and creative performances. I draw upon the art/life principle to study elements of Okinawa’s postwar culture and life that resist histories of imperialist cultural colonization by illuminating the mundane, the common, that which comes from below, and the people, as critical and creative f/actors (factors and actors) in the production of miXtopia.

My methodology aligns with the work of renowned performance artist and theorist, Adrian Piper, who considers her performance art as a methodology which is achieved through an outcome revealed and created in the process of her performing her alter ego in “Mythic Being,” a time-based mixed-media work that Piper performed between 1973-1974 as a male drag artist. The “Mythic Being” appeared both in performances (i.e. as life) in the public streets of New York and as a performative piece (i.e. as image-text) – via the visual image of the “Mythic Being” using photography and text – in the advertising section of the weekly New York magazine, the Village Voice. The performance shows the crossing of art into life, whereby, she says, the experience of performing “becomes part of public history, and no longer her own” (Piper 117). An art activity, she writes, is a “process to make sense of what’s already occurred” and to “make intelligible ex post facto a part of my life that would otherwise remain inexplicable to me” (Piper 1996: 119). Here, performing emerges as a methodology formulated “in the process” of making (sense) of the alter ego as an art/life subject-object interlocutor through movement, continuance, and possibility. The “-ing” signals the experimental praxis of chance, discovery, and the unexpected. As in performance art, it blurs the lines between form (art) and content (life). Read as a figural sign like a hieroglyph, the letter X in miXtopia is capitalized to signify the performative function (the encounters) that are embedded in theory as methodology. I employ X to locate the Okinawan language in the third con/text (the performance of text through the multiple texts and contexts) of champurū (see below) between text and life. What emerges from the encounter, in the Okinawan context, is a third con/text, which the epistemic rupture and rapture of the mixed-multiplying principle of champurū offers as decolonial possibility.

The Mixed-Multiplying Principle of Champurū

Champurū is an Okinawan word that means “mixing” or “being mixed,” which may resemble an act of fusing, but I call it a movement that illuminates the changing nature of Okinawa/n, and is often used to describe the Okinawan cooking style. Champurū culture (champurū bunka) embodies the historical formation of Okinawa’s multicultural identity and society, which can be traced back to the golden era of trade (between the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries) when the island formed part of an independent nation known as the Ryūkyū Kingdom and lay within an East Asia trading zone (Furuki 2003: 24). Building on champurū bunka, I problematize Okinawa’s “American Champurū,” which signals and hails the American presence in Okinawa, as a third con/text between performance and life that speaks across the borders between the US, Japan, and Okinawa in translational acts of speech. As a third text, Okinawa’s American Champurū blurs the boundaries of the nation-state, stretching the function of the Okinawan language beyond western as well as Japanese colonial imaginaries. As a foreign word, it is standard practice to italicize the term champurū, but I use the word without italics in order to maintain the ideographic intent of the term as performative.

Situating the Okinawan language in a decolonial con/text, this article attempts to contribute to transnational and transpacific Asian studies, firstly through the theoretical formulation of the Okinawan concept of champurū as a decolonial lexis, and secondly, through the methodological application of performance art in positioning an understanding of Asia and Asian languages as imperative for knowledge production at the transpacific crossroads in western academies in general, and in the US, the American military presence in Asia, in particular. My framework of champurū as decolonial lexis is based on the principle of what I call mixed-multiplying. I employ an approach that is drawn from performance art to demonstrate the performativity of everyday Okinawan concept such as shī mī (the Okinawan day upon which ancestors are traditionally honored), and Japanese words, kichi (“military base”), and o-warai (“laughter”) as sites of decolonial possibility. Okinawa’s American Champurū is a language of performance art that humors power and laughs at cultural and political domination. Questions that I raise include: How do Okinawans survive and thrive when their everyday lives are haunted by gruesome memories of war, ongoing militarism and foreign military domination, as well as neoliberalism? What is the performance and life of persistence? Where is it manifested, and how is it produced?

Life Matters

Making reference to the longue durée of Okinawa’s multicultural history, Okinawan scholar and theologian, Ronald Y. Nakasone, writes: “the Okinawan cultural fabric is … richly woven with North, East, and Southeast Asian motifs. And the American military presence brings yet another culture into the mix” (Nakasone 2002: 23). An Okinawan scholar and researcher of Japanese literature, Yūten Higa, suggests that the power of champurū resides in the “[c]reativity [that] is the ‘multiplying,’ ‘mixing,’ and ‘combining’ of things … to create a new thing” (Higa 2003: 14). Building on the history and genealogy of this term, I mobilize champurū as a third mode of decolonial practice that is couched in the mundane, where dual-power structures – the military occupation and continuing presence of the US (1945–present), and the imperial legacy of Japan (1879– present) – are re-configured through the mixed-multiplying principle of champurū. I argue that, in a state of constant flow (mixing and multiplying) between power and creation, champurū, as an Okinawan f/actor, has the potential to produce new expressions of life that undermine hegemonic, colonial, imperial, ideological productions (construction, inscription, proscription) of place, “race,” and space. The champurū f/actor functions as an interrupter, a mediator, a wild card, and a form of laughter, offering the potential, the possibility, the option, and the chance for life to persist.

In the Okinawan con/text, this “life” is called nuchi du takara (“life is treasure”), as discussed below. For, in the minds of many Okinawans, this phrase signals the end of the independent Ryūkyū Kingdom, defining the ethos of the time in timeless echoes. The phrase is attributed to the last king of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Sho Nei, who, facing war with Japan, chose life over death, giving up his throne in order to save the lives of his fellow Ryūkyūans (Okinawans). His words reverberate like poetry and are to be found in various ryūka (poems and songs of the Ryūkyūs), traveling across the time and space of history (McCormack 2003; Roberson 2010; Ueunten 2012). Today, the poetics of that precious life survive in the form of communal peace signs commonly seen in various spaces of everyday life in postwar Okinawa. The Japanese term heiwa (平和) means peace and the Okinawan phrase nuchi du takara (命どぅ宝)are seen both in political spaces, such as rallies and sit-ins in front of US military bases, and public spaces, such as venues for stand-up comedy shows, plays, and other performances.

The sentiment of peace, captured in the phrase “life is precious,” exists in the mundane space of everyday yuntaku (“chatting”) with friends and neighbors, thriving within the act of living and through the insistence that Okinawan lives matter. Postwar life in Okinawa is created through the interwoven-ness of colonial, imperial, and racial traces and the spirit of the mundane, giving con/text to life as performing. Here, the mundane f/actor (factor and actor) interrupts the power of domination through wordplay, humor, and laughter, all of which desire not only to survive a disenchanted life, but also to thrive with pleasure. In writing “f/actor,” I assert that the term “actor” refers to an Okinawan subject, while the term “factor” refers to Okinawa as a subject. The pleasure arises from the mundane, living an Okinawan champurū life through the champurū-ing words/worlds of a changing Okinawa while maintaining the champurū f/actor in what is called the Okinawan yu, a concept further explored below.

From Okinawan yu to Champurū yu

Pronounced in Okinawan as yu, in Japanese as yo, and written using the Chinese character世, this word carries a variety of meanings, including “era,” “world,” “style,” “time” or “way.” The affective difference produced in the two pronunciations is illustrated in the following lyrics by the well-known Okinawan minyō (“folk”) songwriter and performer, Kadekaru Rinshō, in his song, Jidai no nagare (The Passage of Time):

唐の世から大和の世、大和の世からアメリカ世、ひるまさ変わたる

この沖縄

Tō no yu kara yamato no yu, yamato no yu kara Amerika yu, hirumasa kawataru kono Okinawa

From the Chinese era, to the Japanese era, to the American era, mysteriously changing, this Okinawa. (Kadekaru 1975) (author’s translation)

While the lyrics refer to historical changes in Okinawa from the prewar to the postwar eras, the last verse, hirumasa kawataru kono Okinawa (“mysteriously changing, this Okinawa”) laments the unchanging nature of present-day times in Okinawa, which is to say that the conditions of colonialism continue to exist today via the long-term US military presence as well as through Japanese political and economic oppression. While the passage of time brings a new era of change, the unchanging nature of conditions on Okinawa is conveyed in the singer’s tone, sensitivity, and style as he portrays post-war Okinawa, champurū-ing the past as part of the present. The kawataru (“changing”) referred to in the verse signifies the unchanging nature of time in Okinawa – the fact that Okinawa’s double colonization continues, even though World War Two has ended – in the double con/text that exposes the colonial traces operating in both the contexts of change and the unchanged. Yudenotes historical time, but also incorporates the connotation of time that does not change in today’s time. The time of the past is in the present, and perhaps in the future too, as songs containing this sense of yu are still being sung, even after the passing of the author of this song, Kadekaru Rinshō (1920--1999).

Various modalities of champurū can be found in different art forms, such as film, theater, stand-up comedy, radio, and novels, that tend to combine hybrid art forms with the un/changing Okinawanyu, making the latter an unequivocally champurū yu. It is in this sense of mixed-multiplying time and space that the Okinawan yu is layered with traces of history, memory and stories that together crave life, freedom, and creativity. The Okinawan pronunciation, yu, denotes a position, situation and tension between uchinanchu (Okinawan) and yamatonchu (Japanese). In this case, the onto-epistemological difference in sound between the Okinawan yu and the Japanese yo presents a soundscape that sets the enduring spirit of uchinanchu that is condensed within the expression nuchi du takara (命どぅ宝) (“life is precious”). While not totally dissimilar to or far removed from the mainland Japanese world outlook, it is nevertheless fundamentally different from it. For, the Okinawan yulives in and out of history in the continuum of the changing yu carried and expressed through the movement of champurū through the borderlands of the Japanese national state, forming its own unique mixture and hybridity.

As mentioned above, postwar Okinawan life is impacted by the dual power structures of US militarism and Japanese imperialism, which continue to produce colonial conditions in Okinawa today. The San Francisco Peace Treaty (1951) and the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (1952), also known as ampo jōyaku(安保条約), established such dual-power domination over Okinawa. Japan surrendered and renounced all of its colonies in August 1945, regaining its independence in 1952, but Okinawa remained formally occupied by the US military until 1972. The Security Treaty allows the US government to continue occupying nearly the same proportion (20%) of the total land area of the main island of Okinawa as was the case in 1945, with thirty-two of the original forty-two bases continuing to operate today. Okinawa, which accounts for only 0.06% of Japan’s total landmass, provides approximately 75% of the land used for US military bases in the country. A March 2013 report showed that 47,300 military personnel and their dependents were stationed in Okinawa (Okinawa Prefecture Website 2013). After Okinawa’s return to Japanese administration, the Tokyo government implemented a series of economic plans that aimed to raise Okinawa’s economy to a level of parity with that of Japan as a whole. Yet, as Gavan McCormack shows, these plans were based on the development model of dependency, structuring Okinawa “as a prefecture within the highly centralized Japanese nation-state; as a ‘base zone’ in which the US military presence is heavily concentrated; as a ‘public works’-centered, regional political economy; and as Japan’s premier ‘resort zone’” (McCormack 2003: 93). Today, Okinawa still suffers economically, ranking as the poorest prefecture in the nation. One of Okinawa’s two major newspapers, the Ryūkyū Shimpō, reported the following 2016 data: “At 25.9 percent, Okinawa has the highest working-poor rate in Japan, which is 9.7 percent higher than the national average. When the survey was previously conducted in 2007, Okinawa’s poverty rate was 20.5 percent. The situation has been steadily worsening, with a 5.4 percent increase since then” (“Okinawa Hits Record High” January 5, 2016).

In this precarious position between two powers, one foreign and another supposedly domestic, some Okinawans perform the “Other” for survival, becoming willing or unwilling participants in neo-liberal multicultural celebrations of postwar champurū culture. However, the purpose of performance is not only to survive the dystopic reality of life, but also to thrive in expressions of decolonial difference, in which another form of life is possible beyond the impossibility of the colonial imaginary of the Other. In this sense, the creative power of champurū transforms “Okinawan” into a critical and creative f/actor that untethers, even temporarily, the colonial, imperial, and racial hold of impossibility through the living of a champurū life.

Okinawa’s American Champurū Text: Do You Shī Mī (シーミー),See Me, or SeeYu?

Okinawa’s in-between-ness as a nation, neither part of Japan nor America, was tangibly produced by the US military occupation of Okinawa (1945-1972), during which some Okinawan cities were transformed into “American towns,” dramatically changing the cultural-economic landscape of cities into mixed Okinawan-American spaces. Koza was one of the first of such American towns. Toshino Iguchi describes the atmosphere of Koza as “peculiar,” characterizing people there as a “third race,” “neither belonging to Japan nor American” (Iguchi 2006: 4). The rise of Okinawa’s American Champurū con/text is closely related to this atmosphere.

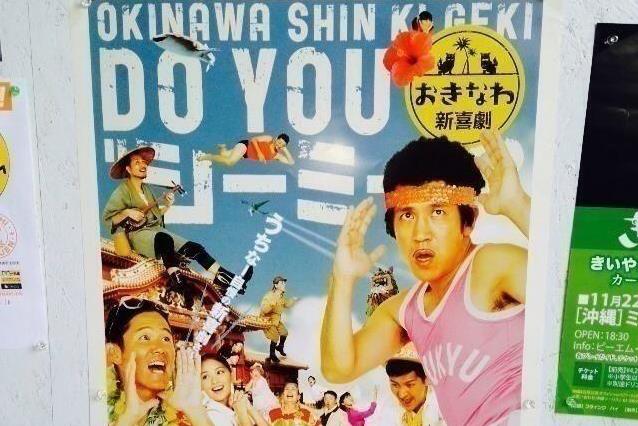

Okinawa’s American Champurū texts incorporate the American context into the Okinawan-Japanese linguistic fold, such texts playfully appropriating the dominant languages, English and Japanese, into mixed lingual forms, contents, and contexts. The champurū f/actor is a ubiquitous multiplier, inserting itself as a gadfly or interrupter that often takes the form of humor and laughter. The champurū con/text is words/world play between power and the mundane, as can be seen in Plate 1, a flyer for a comedy performance entitled, Do You Shī Mī?

Do You Shī Mī? is a musical comedy based on the theme of Shī Mī, an Okinawan tradition in which ancestors are honored that takes place during the lunar New Year in March or April. The musical was produced by popular Okinawan entertainer, Gori. As part of the comedy duo, Garājisēru (Garage Sale), Gori was signed up by Yoshimoto Kōgyō Co., Ltd., a major Japanese entertainment company based in Osaka, in 1995. Established in 1912, the company operates as Japan’s major hub for the comedy entertainment industry. It has expanded to other parts of Asia, producing radio and television shows, commercials, theatrical and comedy performances, while also moving into other lines of business, such as real estate and software development (Yoshimoto Kōgyō Co. Ltd. 2016). Garage Sale began its career with the company in 1995. Gori follows in the footsteps of Yoshimoto Shinkigeki (“New Comedy Theater”), a variety show formerly known as Yoshimoto baraetī (“Yoshimoto Variety”) that was established in 1959. In 2014, Garage Sale created the musical, Do You Shī Mī? as the inaugural production of Okinawa Shinkigeki (“Okinawan New Comedy”) as part of a ten-year arrangement on the Yoshimoto company label. Gori makes the following statement on the popular online travel and entertainment website, Rakuten:

吉本新喜劇の先輩たちが作ってこられた伝統を受け継ぎながら、沖縄の音楽や風習、言葉を“チャンプルー”した「沖縄独特の文化を笑いながら学べるショー」を作っていきたいと思います。

Following in the tradition of the works created by our predecessors at Yoshimoto Shinkigeki, I want to create a “show that [enables the audience to] learn about the unique Okinawan culture through laughter” by “champurūing” Okinawan music, manners, customs, and language.” (Rakuten. 2016; author’s translation)

Operating on a mainstream Japanese label, Gori’s work can be read as a neoliberal project that maintains the structure of power relations between Japan and Okinawa. However, another, more ambiguous reading is also possible, locating the Okinawa American Champurū text that emerges in the following flyer, for example, at the X-point, the crossroads between text and life.

A Flyer for the Okinawan New Comedy performance, Do You ‘Shī Mī? (2014)

Reflecting the performance style, the poster exemplifies the sound, text and performance style of Okinawa’s American Champurū, creating a pastiche of mixed life. Shī Mī is also the Okinawan and Japanese pronunciation of the English expression, “see me,” used commonly in Okinawa due to the American presence. These words here function as a double play between culture, language, customs, and tradition, both American and Okinawan, woven into a comedy using humor and laughter.

A textual reading of the title illustrates the performativity of Okinawa’s American Champurū text similar to what Henry Louis Gates Jr. suggests is the difference between “signification” and signifyin(g,) which gives caché to the treasure of troping as a decolonial multiplier. Whereas the former is a sign predetermined by the rules of linguistic engagement, the latter as a signifier disengages, determining its own course following different trajectories that lead to unanticipated and unexpected outcomes. Because the parallel universe is an inappropriate metaphor for describing the semantic field between black and white in US and western colonial contexts, Gates uses the term “perpendicular” universe to delineate the two differentiated linguistic fields (Gates 1988: 49). In the Okinawan context, I sense the relational similitude between “black and white” and “Okinawan and Japanese,” while the integrity of the relational differences in both pairs remains. What I want to elucidate here is the possibility of the champurū text functioning as a translational method for cross-referencing between “Okinawan” and “black.” Through such a method, Okinawan difference becomes a counterpart to terms denoting black difference as a space in which “[l]inguistic masking” is performed and where a “black person moves freely between two discursive universes” (Gates 1988: 75). Within the Okinawan con/text, it is the champurū f/actor that moves through and in-between at least three discursive universes – Japanese, American, and Okinawan – to create parodies of everyday situations.

Playing with linguistic discursive fields between shī mī(シーミー) and “see me,” bringing in sonic and the cultural con/texts, the American element, “do you,” opens to a kind of spiral thinking, perversely confounding everyone watching the play. The “American presence” is hailed in the text, evoking thepastness of history in the present in what Michel-Rolph Trouillot calls a “position,” where people have three distinctive roles as “agents, actors, and subjects” (Trouillot 1995: 15, 25). Do You Shī Mī brings in those elements as champurū f/actors that conjure up the pastness of war and the military occupation, bringing into view the tripartite relationship between the US, Japan, and Okinawa. While the geopolitics of the US-Japan relationship reproduce Okinawa’s colonial present, the mundane as a site of critical and creative options offers the potential for the insertion of a champurū f/actor, the performance of epistemic disobedience that, according to Walter D. Mignolo, “takes us to a difference place, to a different ‘beginning’…” (Mignolo 2011: 45). In performance theory, it is José Muñoz’s concept of “disidentification” that shows a third subjectivity between “Okinawan” and “Japanese” that when “dealing with dominant ideology (…) neither opts to assimilate within such a structure nor strictly opposes it; rather disidentification is a strategy that works on and against dominant ideology” (Muñoz 1999: 11-12). The mixed-lingual effect of the third text in the Okinawan con/text provides buoyancy between and beyond Mignolo and Muñoz’s differential movements. In what is, precisely, a champurūing moment of simultaneous and multiple movements that constantly disrupt and destabilize the dominant cultural norm, the serious is turned into the funny and the sad into the happy. Through champurū, life becomes performative, while resistance takes the form of comedy.

Kichigai or Crazy? Flow and Flux Between Text and Life

Champurūing as a decolonizing form of life-performance can be seen in many examples of wordplay found in modern-day Okinawan. For example, the champurūing of the Japanese word kichigai (“outside of the (military) base”) – a combination of the word kichi (“military base”) and gai (“outside of”) – illustrates how Okinawa’s American Champurū is deployed as a textual medium of linguistic performance. Here, it is important to note that a common Japanese homonym of kichigai (written with different characters) means “crazy.” Together, the wordplay described below can convey the message that it is crazy for there to be such an extensive US military presence in Okinawa today. All of the following characters are read as kichigai, with each conveying different meanings:

基地外: “outside of the US military bases”

基地害: “damage and harm caused by the military bases”

基地ガイ: “a guy from the military bases” (with the part meaning “guy” written in katakana, the Japanese alphabet used to write foreign words and loan-words)

基地GUY : “a guy from the military bases” (with the English word tacked on to the kanji, Chinese characters used in Japanese)

気違い: “a crazy, lunatic, or insane person”

The Japanese language allows for orthography to combine forms, sounds, and even shapes through the combination of different writing systems. Standard Japanese is written using a combination of kanji(Chinese characters), hiragana (the Japanese syllabary used for native words), and katakana(the Japanese syllabary mostly used to signify foreign words that have been incorporated into Japanese). Combining these elements with uchināguchi (the Okinawan language) in various forms and incorporating English words (as seen in the Shī Mī example above), champurū performances can deliver powerful messages.

To contextualize the word kichigai, I begin with the word kichi (“military base”). This term, commonly used in Okinawa, is also a visceral sign and a solid reminder of the past, the present, and the future of an (un)changing yu. While wordplay might shatter the silent acquiescence found in the standard use of the term, such words are very much part of the everyday life and psyche of Okinawa/ns. For example, the homonyms listed above expose the lunacy and the fallacy of the logic behind the idea that the US military presence in Asia secures peace. This myth is juxtaposed with historical and present-day realities, in which ongoing incidences of sexual assault and other violent crimes committed in Okinawa by US servicemen remain unresolved matters that continue to haunt the present. Thus, in Okinawa, the word kichigai (“outside of the base”) does not connote a space for peace, but a locational and temporal con/text for each of the crimes committed by US military personnel against Okinawan civilians outside of their bases. Here, wordplay becomes visceral and external beyond the text, opening the door ajar to decades of historical references to the exploitation and mistreatment of Okinawa and its people.

The latest crime committed by a former military guy, a “kichi guy” is a case in point, where the word shows the world what is kichigai or crazy about the American yu. On May 19, 2016, the body of a twenty-year-old Okinawan woman from Urama City, Rina Shimabukuro, was found in a mountainous area of Onna City. A suspect was taken into custody, a thirty-five-year-old ex-Marine who goes by the name of Kenneth Shinzato, having adopted the family name of his Okinawan wife who is not the victim. He is a military guy (a “kichi guy”) who used to work at one of the largest US military bases in the world, Kadena Air Force Base, which was built in 1945 and continues to operate in Okinawa to this day.

This incident is a reminder of the role played by champurū in working to retain the past in the present. Here, it may be helpful to consider Catherine Walsh’s notion of the “decolonial crack” of “insurgents” as a transformative move from rupture to rapture. In her work, the “crack” is a decolonial possibility that creates life that is otherwise, a way of being and thinking differently (Walsh 2014). By connecting unknown stories concerning crimes committed by US military men such as the one mentioned above, “cracks” open up to a story that keeps signifyin(g) the past within the present in a champurū mode, i.e. kichigai, kichi guy, etc. News about such crimes exposes, in a mixed-multiplying movement, the fallacy of peace and the legacy of colonial, imperial, racial, and structural violence that occurred in the past, continues to occur in the present, and, undoubtedly, will continue to occur in the future. Suddenly, there is a realization that the mundane does not exist in Okinawa, given the continuing realities of colonial dominance, military occupation, sexual and racial violence, and ongoing ethnocide. The textual crack thus produces a real fissure, revealing a broader story and a deeper history. Champurūing allows these cracks and fissures to reveal the ongoing dehumanization of Okinawans, calling for a reexamination of militarism that involves repositioning the American kichias an American problem.

Kichinai(基地内)(“Inside the Base”) and Kichi Nai (基地無い) (“Having No Base”)

Another interesting example of champurūing involves the homonyms kichinaiand kichi nai. While the former term means “(the) inside (of) the base,” the latter carries a connotation of not being able to access the inside of the base and/or a feeling of not wanting the bases at all, performing a re-drawing of the contested borders between the military bases and Okinawan native spaces and reinforcing the separation between an external power and local people. The US military bases are a daily reminder to Okinawans that their land was bulldozed, destroyed, and taken away from them, with no regard to whether or not such land included homes or family tombs. As a result of such actions, many Okinawan homes and ancestral burial places are now located inside the bases, or in spaces known as kichinai (基地内). Against such a backdrop, a third con/text of ancestral space exists as a possibility. According to Okinawan tradition, ancestors are considered to exist amongst the living, their tombs and gravesites commonly used for all-day family picnics at which family members, both living and dead, may spend time with each other. Such gatherings take place on an annual basis, and are known as shī mī (see above). Some family tombs were destroyed during the construction of the bases, while others ended up inside the bases. In the latter type of situation, families are required to obtain permission each year in order to gain temporary access to the bases where their ancestors’ tombs are located in order to continue the tradition of shī mī. Some Okinawans have built new tombs outside of the bases, enabling them to participate in the annual family gatherings without having to obtain permission to access the tombs. In cases such as these, the ancestral tombs are split between sites located both inside and outside the bases. This haunting in-between-ness of place and space produces the spirit of the champurū text that performs the paradox of an everyday life split between kichinai (“inside the base”) and kichi nai (“no base”). In champurūing the kichi-gai-ness (“craziness”) of life, yet aspiring toward kichi-nai-ness (“liberated from the base”), Okinawans try to laugh, bringing an element of o-warai, (“laughter”) into the everyday, as will be shown and discussed in the remainder of this article.

O-warai: Historical Laughter from Below

O-warai is a Japanese noun meaning “laughter,” and is often used with the particular connotation of satirical laughter directed at the powerful. Champurū is permeated with ironic twists, such as that involved when deploying warai(without the honorific o) as a parody of real life and times. It is possible to trace the historical roots of laughter in the context of Okinawan life back to the conclusion of the Battle of Okinawa. The story begins with famous comedian Onaha Būten’s popularization of the phrase nuchinu gusūji sabira (ぬちぬぐすーじさびら), which can be translated as: “let’s celebrate life.” Būten was referring to life in the internment camp where Okinawan civilians were incarcerated by the American military. On April 2, 1945, American military forces occupied a central area of Okinawa near the seaport of Awase. They rapidly built twelve refugee camps throughout the island. The camps housed 250,000 Okinawans, who were forced to move from one location to the next according to the military’s changing strategic needs (Fisch 1988: 55 – 57). After Okinawans had sacrificed themselves on behalf of the Japanese, survivors ended up being treated as prisoners in their own land.

It was in the Ishikawa internment camp where Būten was taken that he gave the term nuchinu gusūji sabira (“let’s celebrate life”) a new meaning through performance in the face of the death and destruction of human life. Later, I will argue, it developed into a philosophy of laughter as a way of life in this particular con/text. Būten gave death a meaningful life through art, transforming an impossible situation into a possible situation comedy. To awaken the spirit of Okinawans, he used humor, “playing sanshin (an Okinawan musical instrument) with a raucous sound,jaka jaka jaka jan!, overlaying an impromptu song over a traditional minyō (“folk song”), and performing a strange dance by demolishing the quietude of the Okinawan traditional dance form” (“Nuchinu gusūji sabira” January 1, 2015; author’s translation). Combining a strange style with an impossible idea, Būten performed in order to convince survivors that life should be celebrated, even more so in the midst of sorrow and hopelessness. Initially, many viewed his efforts as strange or crazy, but he eventually managed to win over the hearts of Okinawans, whose spirits were rescued through comedy that incorporated multiple meanings. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of his father’s passing, Būten’s eldest son, Onaha Zenkō, wrote the following, rephrasing previous comments by Būten’s protégé, Teruya Rinsuke, : “[we] cannot measure or know how much the teacher’s [Būten’s] laughter has saved [the spirits of] those who have been broken” (Onaha 1994). The laughter referred involves moments of communal transformation in which life is doubly celebrated – both for the living and for the dead. The shī mī ritual is a site and act of resilience and a celebration of life in which the ancestors are honored in the hope of peace for the living as well as the dead. Būten’s unique style of performance, involving both stand-up and sit-down comedy, employs wordplay, puns, and storytelling to reclaim Okinawan stories from below, from the common folk, criticizing and denouncing the multitude of power – whether it be imperial, colonial, or military – through laughter. I suggest that there is a direct correspondence between Būten’s nuchinu gusūji sabira (“let’s celebrate life”) and nuchi du takara(“life is treasure”) another phrase that expresses the spirit and determination of Okinawans to choose life over death through celebration. The witty deployment of wordplay in his particular style of performance is grounded in everyday life, deploying and mixing linguistics, politics and social commentary in the context of critical performance.

The following discussion relates to the contents of three titles that are included on the CD,Okinawa mandan: Būten warai no sekai. Vol. 2 (“Okinawa Comedy: Būten’s World of Laughter. Vol. 2”). The first story, Sekai Manyū (世界漫遊 or “World Pleasure Tour”), concerns a man named Mankū. Although not smart, he somehow stumbles upon the chance to travel around the world, returning to tell funny tales about his encounters in various countries. The second story, Sūyā Nu Pāpā (すーやーぬパーパー or “The Owner of a Salt Manufacturing Store”), is about the owner of a salt manufacturing store who tries to take his bride to a hārī festival (an annual boat race involving traditional Okinawan fishermen), but never ends up making it to the event due to a stream of passersby who keep him trapped chatting about mundane aspects of daily life. The third story, Inuneko Kidan (犬猫綺談 or “A Funny Tale about a Cat and a Dog”), concerns animals that are competing for selection as one of the King’s twelve pets who will live with him in his castle. The cat that finishes in thirteenth place tries to convince the King that he has made a mistake, and that the cat should be selected as one of the twelve animals. The comical story goes on to deal with the issue of who is worthy of being selected as one of the chosen twelve. In common with Būten’s other work, these three performances are presented as monologues that mix clever lines, rhythmic flow, and intervals, the performer sometimes using his own voice to imitate the sounds of animals and musical instruments. Such performances, themselves examples of mixed-multiplying co-motion, capture the souls of Okinawan folk with humor and laughter that are embedded in the third space between text and life. In the second story, while telling a story about kamadū(“hearth” in Okinawan; also a common term for “grandma”), Būten holds the last syllable, dū, for eleven seconds, maintaining a low steady tone, “duuuuuuuuuuuuuu,” before continuing with the rest of the story. In the sustained vibration of the dū sound, which disrupts time and space, the audience is thrown off and into a nonsensical space that produces laughter, as if sense is being made from nonsense. In the introductory notes included with the CD, one entertainer suggests that while Būten had no control over the external world, he used laughter as a means of liberating himself from a world suffering from various sources of distress, such as war.

Būten’s famous sketch, “Hittoraa” (the Japanese pronunciation of “Hitler) is one of the best examples of this type of performance. In this sketch, Hitler is the object of wordplay, deployed via a champurū text in which Būten reworks form, content, and context through tonality and rhythm, remixing and multiplying stories via comedic parody. His clever use of multiple tongues creates a fabulous composition that combines and juxtaposes the Okinawan language and Japanese pronunciation, as well as references to Hitler’s German military, the US military occupation, and the Japanese imperial legacy. “Hitler” is pronounced “Hittoraa” in Japanese, but pronounced “Hitturuu” in Okinawan. Used as a verb, (hitturuu), this term means “to steal” or “to rob.” His deliberate and clever use of double entendre transfigures the proper noun Hittoraainto the verb hitturuu. The morphed name is English and Okinawan, producing a different meaning and context by which to deliver an allegory concerning the complex situation in Okinawa as seen from an Okinawan perspective. In the sketch, he asks the rhetorical question, “Do you know why they call him Hitler/Hittoraa (in Japanese)?” “It’s because he is a hittoraa/thief (in Okinawan).” In this trans-positioning of texts, Būten evokes the history of imperialism and colonialism in Okinawa, a history in which theft of life has also taken place. It is precisely this process of mix-multiplication that produces miXtopia. The dominated have turned the tables and are no longer powerless, subverting the meaning of power through Okinawan laughter.

Kichi as a Site of Laughter

Another example of turning endurance of oppression into laughter comes from a documentary entitled Okinawa Laughs: 100 Years of Stories: Laughing (at the) US Military Bases: O-warai Beigun Kichi(Laugh(able) US Military Bases, or OBK) (broadcast on NHK Japan, June 18, 2011), a historical chronicle of Okinawa as seen through performances that produce laughter. The documentary features the contemporary performance group, FEC (Free Enjoy Company, established in 1994), who started the OBK series in 2005. The series has become so popular that most of the shows sell out within days. In 2016, the twelfth performance in the OBK series was held in Naha, Okinawa. Afterwards, the following appraisal appeared in one of the two major Okinawan newspapers, Ryūkyū Shimpō:

米軍基地や安保法制など沖縄と安全保障にまつわる問題を鋭く風刺し、沖縄に過重な負担を押し付ける背景を笑いの中に浮かび上がらせる新作に会場からは拍手が絶えなかった。

The audience could not stop applauding [after watching] the new [OBK] skit that brought to the surface, by way of sharp satiric laughter, a background in which an excessive burden is placed upon Okinawa through the US military bases and the US-Japan Security Treaty. (“Okinawa no ima” June 12, 2016; author’s translation)

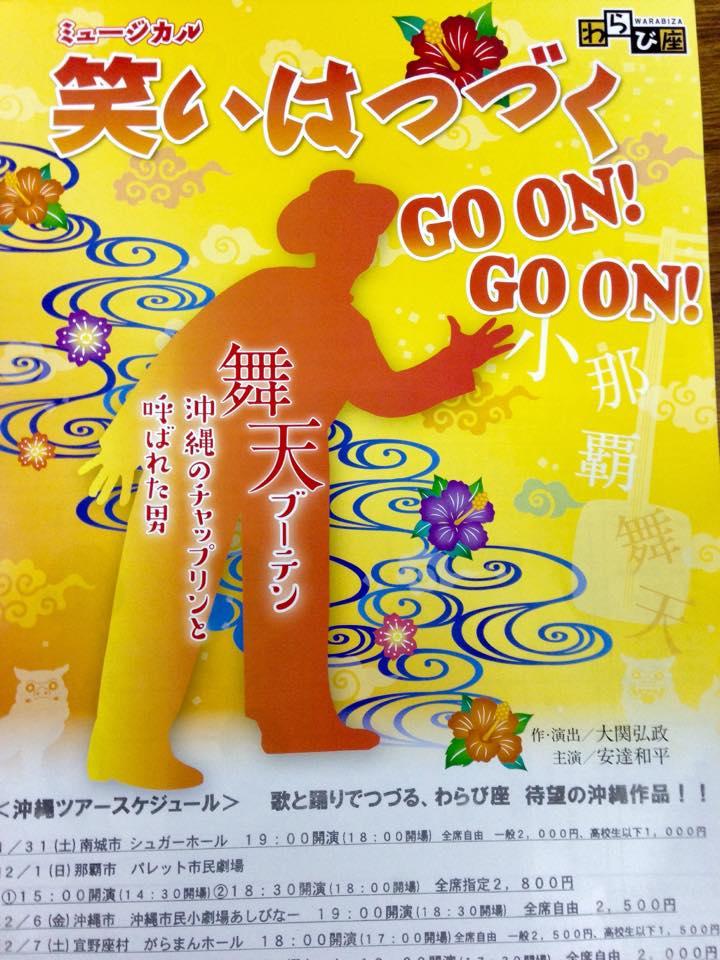

This unstoppable applause tropes, so to speak, another example of unstoppable historical laughter that continues mixed-multiplying one-hundred-year-old historical events into the present, Warai Wa Tsuzuku Go On! Go On! (笑いはつづくGo On! Go On! or Laughter Continues Go On! Go On!), a musical based on Būten’s life that was performed on stage in 2015.

The Būten musical, Laughter Continues Go On! Go On! (January 2015)

The 500-seat Sugar Hill Concert Hall in Nakagusuku City, Okinawa sold out for the opening night of the show on January 31, 2015. Tsukasa Sogabe, Būten’s biographer, postulates rather hastily that people are “ignoring the [importance of] ‘laughter’ in history. Or, should I say, they are consciously trying to forget. […] Is it that those who experienced and survived the war have permanently erased “laughter” from their memories?” (Sogabe 2006: 1-2; author’s translation). Because there is a lack of documentation, he thinks that there is a lack of interest or awareness of the importance of Būten’s laughter in the context of people’s experiences or memories of him, of laughter, and/or of war. I argue that it is precisely the unwritten, the invisible, and the mundane that live on in his practice, where laughter is used to make sense of nonsensical aspects of the modern-day world. It is the performance of his theory as a theater of the everyday, not a history of the past, which gives the soulfulness of laughter the desire to go on and go on. In the biography, Sogabe interviews an elderly woman in her eighties, who recalls the time that she spent in an interment camp where she and others witnessed Būten’s art of performance as “the happiest. […] Parents were killed, children died, we were all burdened by the same misery. The Americans provided us with provisions while families lived in tents, and we were able to feel that we could live happily” (Sogabe 2006: 91; author’s translation). Even without laughter, the meaning of life still lives on through experience, remembering and laughing about that time in today’s time. In the next sentence, the author describes how the elderly woman, after pausing for a moment, “laughed out loud as if she had felt something [and], without focusing, looked intently out over the ocean with a smile on her face” (Sogabe 2006: 91; author’s translation).

While Būten’s o-warai depicts the overlapping worlds of pre- and post-war Okinawan, Japanese, and American yu, comedic performances by younger artists, such as FEC’s O-warai Beigun Kichi (Laugh(able) US Military Bases) series, continue the legacy of laughter by performing life in their own yu,that is to say, the life world and ethos of the younger generation. In the aforementioned documentary, the video begins with an Okinawan minyō (“folk song”), performed in uchināguchi with the following Japanese translation shown on the screen: “Okinawa no kamisama wa o-warai ga daisuki. Sensō wa kirai” (The gods of Okinawa love laughter. They hate war.). This is preceded by video/film footage of US military aircraft flying over a neighborhood. Next, the narrator comments on the burden placed on Okinawa by the military bases, after which the documentary cuts to a short clip from a live OBK performance called “JapaNet” that was performed at Futenma, the center of the current dispute involving the military bases. In the skit, we firstly see laughter, then an image of the audience, followed by the following lines delivered by the performers on the stage:

沖縄の特産品を本土の皆さんにお届けする

「ジャパネット沖縄」の時間です。

今回皆様にご提供する御商品はこちら。

沖縄のアメリカ軍普天間基地です!

It’s “Okinawan JapaNet” time.

We are going to offer a specialty from Okinawa to everyone in mainland [Japan].

Today, we offer you this product.

It’s Futenma, Okinawa’s American military base!

[An image of the base is simultaneously projected on the screen]

(Okinawa Laughs; author’s translation)

The audience erupts in hearty laughter, a sound that involves the expression of both pleasure and displeasure. The performance exposes the falsity of the twenty-year old promise made in 1996 to relocate the Marine Corps base at Futenma to Ginowan. “JapaNet” [1]alludes to the heavy concentration of military bases on Okinawa, 74% of the land used for such bases in Japan being concentrated in an area (Okinawa) that accounts for only 0.06% of the nation’s total landmass. In the sketch, Futenma base is packaged as a commodity, advertised as an Okinawan product, and offered to the Japanese government as an example of a local specialty. In this close mimicry of life as real performance, laughter erupts at the absurdity that keeps Okinawans outside of Okinawa: Okinawans are prohibited to go onto the bases – kichinai– while military personnel are allowed to travel freely outside of them – kichigai.

The lucidity of the juxtaposition of art and life, as captured in this performance, is the champurū f/actor, creating a third performative space in which life is the material for the stage, revealing the slippages between reality/life and performance/art. In many postwar Okinawan performances, current issues, such as militarization and politics, become everyday storylines that are quickly turned into artistic performances.

Yet, for some critics, the contents of such performances are too close for comfort, leading them to criticize the performance’s direct and indirect criticism of Japan’s imperial past and present that emerge from such encounters between reality and parody. In a Japanese Tumbler thread, the writer of one entry, headed, Ōshitsu wo gurōshita Okinawa o-warai geinin (皇室を愚弄した沖縄お笑い芸人 or “Okinawan comedians who ridiculed the Imperial lineage”) responds angrily: “This is not a comedy, it is racism! If they broadcast this in the US, they would be sued immediately” (author’s translation). Here, the gap between “laughter” and “anger” is the art/life X where Okinawa and Japan meet. While the “anger” represents the conflict of opposition, the “laughter” is a contradiction that offers a third con/text of possibility. In an interview for weekly online magazine Excite, OBK creator Masamitsu Kohatsu offers an insight into the necessity of laughter among the contradictions of life in Okinawa alongside the US military bases.

矛盾が当たり前のように同居してるのが沖縄なんですね。芸人の立場からすれば、基地がいつまでもあればネタには尽きないし(苦笑)。でも沖縄の人間として は早く基地がなくなってほしいし、この舞台ができなくなることを望んでいる自分もいる。沖縄の人の日常って、そういうものなんです。

Okinawa is [about] coexisting as though contradictions were a matter of course. From the perspective of artists, we will never run out of material so long as the bases continue to exist (wry smile). However, as an Okinawan, I want to be rid of the bases, [even if this means] hoping for the disappearance of this [type of] performance. This is the everyday reality for the people of Okinawa. (Hasegawa 2012; author’s translation)

Laughter, again, is a third con/text that artfully and mindfully plays with Okinawa’s American champurū situation, a situation involving not only the past, but also the present.

The documentary mentioned earlier, which is narrated by Kohatsu, shows that laughter is a survival mechanism that has been embraced by these Okinawan performers, and, by extension, the Okinawan people at large. From FEC, as well as many other groups, past and present, right up to the godfather, Būten, laughter is deployed as a lifeline linking the present to multiple and often hidden pasts. Lines in each script are taken directly from everyday life in Okinawa. As such, they are quintessential examples of champurūing. Champurūing history in the present illuminates the continuity of reality in Okinawa: nuchi du takara (“life is precious”) and nuchi nu gusūji sabira (“the celebration of life”). In the spirit of commensurability, some of us Okinawans deploy the expression, Okinawan Lives Matter, resonating in relational similitude (Foucault 1983: 44) with the concept, Black Lives Matter, overlaying the history of African Americans onto the Okinawan con/text. At the crossroads of Okinawan and African American lives, champurū yu mixes and multiplies lives that matter. If one were to become fixated with the world of American militarism and Japanese neoliberalism, one would risk becoming an effigy of the colonial gaze. The pleasure of the mixed-multiplying lifeline offers a decolonial possibility through the con/text of champurū, through laughter, whether it be via Okinawa’s American Champurū or simply through an Okinawan champurū that is able to interrupt the gaze by “misbehavin’” or laughing at the kichi, the military bases that gigantically embody the multitude of power. In so doing, life becomes performance at the X between art and life, which is what occurs in Okinawa-related performance art that is performed there.

In the documentary, the late Teruya Rinsuke (1929-2005), also known as Terurin, elects himself as the president of Koza (now Okinawa City), asserting his independence through a parody of real life. In his capacity as president, he declares the city an independent nation, using life as a stage for the performance of his own independent life through the medium of champurū. As both comedian and musician, he also coined the term, champurūrizumu (“champurū rhythm”), performing champurū-style shows that depicted his life under the US military occupation. A contemporary version of Terurin’s famous 1955 stage performance Watabū Show has been performed by a traditional Okinawan theater actor. The contemporary version incorporates the original 1955 performance, itself not “original,” but a champurūed version of earlier Okinawan plays and stories that had been made into a performance. Being an example of champurū means that no authority is retained for the “original,” yet this is precisely the foundation of a mixed-multiplying principle that brings to light the pleasure of the mysterious, of unknown f/actors that are just waiting to be discovered and hurled into the mix, eliciting a response that involves the laughing off of the pains of everyday life.

Pleasure and Pain

In the context of Okinawa, the ideology of peace maintains the logic of the US military bases, even while Okinawans’ right to live peacefully – evoked in the expression nuchi du takara (“life is precious”) – falls outside such logic. Side by side with the hysterical laughter that is directed toward the US military bases lies a reality in which violence, rape, and murder continue to take place. From the rape and murder of six-year-old Yumiko in 1955 to the abduction and gang-rape of a twelve-year-old Okinawan girl in 1995, and on to the most recent incident, involving rape and murder, that was mentioned earlier, Okinawa has sustained and continues to sustain direct acts of violence by US military personnel, as well as structural violence that is the product of the ongoing presence of the US military bases: environmental devastation, hazardous accidents, and the enormous human cost, a result of the reduction of the Okinawan economy to a kind of cross between a tourist Disneyland and a garrison town filled with sex-related businesses and entertainment. The kichi become part of the everyday physio-psychological landscape of Okinawa, with unresolved matters within unforgotten memories trapped inside the texts and outside the real bodies of those who cannot speak. This unspeakability has been released through one hundred years of laughter, with champurū continuing to unearth the dead, mention the unmentionable, and reveal the inside that the outside does not want to be seen. Laughter is also a form of release that makes quick transitions, moving from the issue of rape victims (pain) to comedy (pleasure), from one moment to the next negotiating the threshold between pain and pleasure without interruption, showing a continuity of history that continues to haunt (as seen in the ancestral rites of Shī mī). In this flow, I stress the element of radicalization that champurū can bring out as a decolonial or decolonizing moment. The champurū f/actor destabilizes epistemic colonial, imperial, and racial violence against life based on the mixed-multiplying principle of nuchi du takara (“life is precious”), precious life that is performing.

References

7ybaru08. 2009. Kawariyuku jidai no naka de. Sadoyama Yutaka no ‘aguaa.’ 変わりゆく時代の で(佐渡山豊のカヴァー). (In Changing Times. Yutaka Sadoyama’s ‘Ouch!’). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWF6ghW1qR8 (accessed March 15, 2015).

A&W. 2016. “A&W Celebrates 50 Years in Okinawa! | Japan Update.” http://www.japanupdate.com/2013/11/aw-celebrates-50-years-in-okinawa/ (accessed April 19, 2016)

Allan, David. 2016. “Helo Crashes on Okinawa Campus.” Stars and Stripes. http://www.stripes.com/news/helo-crashes-on-okinawa-campus-1.23241 (accessed September 12, 2016).

Asahi Shimbun Digital. 2016. Zaioki beigun toppu ga shazai ‘hijō ni hajiteiru’ moto beihei kiken (在沖米軍トップが謝罪「非常に恥じている」 元米兵事件) (Top US Military Official in Okinawa Apologizes [is Extremely Embarrassed] by Incident Caused by Former Military Personnel). Asahi Shimbun Digitaru(朝日新聞デジタル). http://www.asahi.com/articles/ASJ5N63M4J5NTIPE02J.html(accessed May 21, 2016).

Asahi Shimbun. 2016. “Okinawa Base Worker Held in Connection with Missing Woman. http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201605190062.html (accessed May 12, 2016)

Bhabha, Homi K. 2004. The Location of Culture. London; New York: Routledge.

Cavallo, Marco. 2015. Warau Okinawa: hyakunen no monogatari o-warai beigun kichi(笑う沖縄100年の物語 お笑い米軍基地)(Okinawa Laughs: One Hundred Years of Stories: Laughing [at The] US Military Bases), video broadcast on NHK TV, November 18, 2011. http://www.tunesbaby.com/dm/?x=xnthxk (accessed 4 December 4, 2015).

Christy, Alan S. 1993. “The Making of Imperial Subjects in Okinawa.” Positions 1 (3): 607-39.

Daiokishin 630bai okinawashi doramukan. Karehazai shuyo seibun mo. (ダイオキシン630倍 沖縄市ドラム缶、枯れ葉剤主要成分も) (Drum Cans Found in Okinawa City with Dioxin Levels 630 Times Higher than Environmental Standards [Relating to Water Pollution]. High Levels of Defoliants Also Found).Ryūkyū Shimpō (琉球新報),December 12, 2015. http://ryukyuryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-187264.html (accessed January 14, 2016).

De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Engel, Pamela et al. 2016. “Japan’s Prime Minister Publicly Scolded Obama to His Face over ‘Despicable’ Okinawa Murder.” Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/shinzo-abe-obama-okinawa-murder-2016-5(accessed May 2, 2016).

Fanon, Frantz. 2008. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: New York: Grove Press.

FEC. 2016. O-warai beigun kichi(お笑い米軍基地)(Laugh at the US Military Bases). http://www.fec.asia/owaraibeigunkichi/index.html (accessed March 22, 2016).

Fisch, Arnold G. Jr. 1988. “Military Government in The Ryūkyū Islands, 1945–1950.” US Army Center of Military History CMH Publications Catalog. http://www.history.army.mil/catalog/pubs/30/30-11.html (accessed November 18, 2015).

Foucault, Michel. 1994. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage Books.

———. 1983.This Is Not a Pipe. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Furuki, Yoshiaki. 2003. “Considering Okinawa as a Frontier.” Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity. Glen D. Hook and Richard Siddle, eds. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

Fusco, Coco. 1995. English Is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas. New York: New Press.

Garber, Marjorie B. 1992. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing & Cultural Anxiety. New York: Routledge.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gómez-Peña, Guillermo. 1996. The New World Border: Prophecies, Poems & Loqueras for the End of the Century. San Francisco, CA: City Lights.

Hasegawa, Hirokazu. 2012. Kichi mondai wo tobase! Okinawa geinōjin: Kohatsu Masamitsu. “AKB48 no wadai to onaji yōni kichi mondai wo katararete hoshī.” 基地問題を笑い飛ばせ! 沖縄芸人・小波津正光「AKB48の話題と同じように基地問題も語られてほしい」 (“Laugh at the US military base Issue! Okinawan Entertainer, Kohatsu Masamitsu: “I want people to] take up the military base issue like [they did with] the AKB 48 issue.”) Excite, July 14. http://www.excite.co.jp/News/column_g/20120714/Shueishapn_20120714_12572.html(accessed October 20, 2016).

Higa, Yūten. 2003. Okinawa champurū bunka sōzōron 沖縄チャンプルー文化創造論(A Theory of Creativity: Okinawa’s Champurū Culture). Gushikawa: Yui Shuppan.

Iguchi, Toshino. 2006. “Cultural Friction in Koza: Okinawa under American Occupation in the Cold War.” Presentation. Proceedings of International Committee of Design History and Studies ICDHS. 5th Conference, Helsinki August 23, 2006.

itou228. 2016. Okinawa de kurikaesareru beigun hanzai: Kokuren 沖縄で繰り返される米軍犯罪:国連 U.N. (U.N.: Recurring Crimes Committed by the US Military in Okinawa). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGzaU1zEnrw(accessed May 22, 2016)

Kadekaru, Rinshō. 1975. Jidai no nagare. Uta asobi: Kadekaru Rinshō no sekai. 時代の流れ:唄遊び・嘉手苅林昌の世界 (The Passage of Time: Playing with Song: Kadekaru Rinshō’s World). Koza City: Japan Columbia Music Entertainment. CD.

———. 2016.Rinshō Kadekaru – Jidai No Nagare 嘉手苅林昌 . 時代(Kadekaru Rinshō: The Passage of Time). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4DfFGXeq_o (accessed September 13, 2016).

Kaprow, Allan, and Jeff Kelley. 2003.Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kasuru Gappai. 2015. Sadoyama Yutaka “Duchuimunui” 佐渡山豊ドゥーチュイムニィ(一人言)(Sadoyama Yutaka: “Talking to Myself”). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ed5Ry99Ck1U(accessed October 14, 2016)

Kōhō Okinawa jūgatsugō no. 484. 広報おきなわ10月号No.484. (Okinawa Report: October issue, No. 484). Okinawa City Office website. 2014. http://www.city.okinawa.okinawa.jp/kouhou/H26/10/04.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

Lugones, Maria. 2003. Pilgrimages = Peregrinajes : Theorizing Coalition against Multiple Oppressions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

McCormack, Gavan. 2003. “Okinawa and the Structure of Dependence.” Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity, eds. Richard Siddle and Glen D. Hook. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 93-113.

———. 2009. “Okinawa’s Turbulent 400 Years.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 7, Issue 3, No. 3 Online: http://apjjf.org/-Gavan-McCormack/3011/article.html.

Memo-memo. 2014. O-warai: tennō o gurōshita Okinawa o-warai geinin (お笑い 皇室を愚弄した沖縄お笑い芸人) (Comedy: Okinawan Comedians Who Ridiculed the Imperial Family]. Memo-Memo Blog Tumbler. June 13. https://memo-memo-blog.tumblr.com/post/88645579628/%E7%9A%87%E5%AE%A4%E3%82%92%E6%84%9A%E5%BC%84%E3%81%97%E3%81%9F%E6%B2%96%E7%B8%84%E3%81%8A%E7%AC%91%E3%81%84%E8%8A%B8%E4%BA%BA (accessed October 20, 2015).

Mignolo, Walter D. 2011. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (2). http://escholarship.org/uc/item/62j3w283(accessed April 2, 2016).

Mitchell, Jon. 2016. “Agent Orange and Okinawa: The Story So Far.” The Japan Times. http://features.japantimes.co.jp/agent-orange-in-okinawa/(accessed April 28, 2016).

Montano, Linda. 2000. Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties: Sex, Food, Money/Fame, Ritual/Death. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mugge, Robert. 1980. Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise. Film. Mug-shot Productions.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Cultural Studies of the Americas: V. 2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Nakasone, Ronald Y. 2002. Okinawan Diaspora. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002, 3-25.

Nikkan Gendai Digital Magazine. 2016. Okinawa josei shitai iki jiken reipu satsugai mitometa motobeihei no ‘sujō.’ 沖縄女性死体遺棄事件 レイプ殺害認めた元米兵の‘素性.’ (Incident Involving the Abandoned Corpse of an Okinawan Woman: “Identity” of Former American Soldier Who Admitted to Rape and Murder). Nikkei Gendai(日刊ゲンダイ). http://www.nikkan-gendai.com/articles/view/newsx/181877(accessed May, 21 2016).

“Nuchinu gusūji sabira. Okinawa no chappurin: onaha būten 1897 – 1969.” ヌチヌグクージサビラ。沖縄のチャップリン。小那覇舞天 1897-1969. (Let’s Celebrate Life. Okinawa’s Chaplain: Onaha Būten (1897 - 1969)). Okinawa Taimuzu (沖縄タイムズ). January 1, 2015, section 4. Uruma City Public Library (accessed October 3, 2016).

“Okinawa Hits Record High Child Poverty Rate of 37%, 2.7 Times Higher than 2012 Nationwide Rate.” Ryūkyū Shimpō (琉球新報). January 5, 2016. http://english.ryukyushimpo.jp/2016/01/11/24309/ (accessed October 20, 2016).

“Okinawa no ima. Warai de tou. FEC ‘O-warai beigun kichi 12’ sutāto”(沖縄の今、笑いで問う FEC「お笑い米軍基地12」スタート).(Okinawa Now. Inquire Using Laughter. FEC’s “Laugh [at the] US Military Base 12” Launches. Ryūkyū Shimpō (琉球新報).June 12, 2016. http://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-296464.html(accessed June 13, 2016).

Okinawa Prefecture Website. 2013. Okinawa no beigun kichi: heisei 25nen sangatsu: okinawaken (沖縄の米軍基地 平成25年3月/沖縄県) (Okinawa’s US Military Bases: March 2013: Okinawa Prefecture) ( http://www.pref.okinawa.jp/site/chijiko/kichitai/documents/dai1syou.pdf) http://www.pref.okinawa.jp/site/chijiko/kichitai/okinawanobeigunnkiti2503.html (accessed October 20, 2016).

Okinawa Prefecture Website. 2015. Kichi taisakuka meinpeji (Eigo): Okinawaken(基地対策課メインページ(英語)/沖縄県) (US Military Bases in Okinawa: Main Page (English): Okinawa Prefecture). http://www.pref.okinawa.jp/site/chijiko/kichitai/25185.html (accessed May 22, 2015).

Okinawa Times Plus News. 2015. Būten san chokusetsu memo shokōkan. Uruma-shi de raigetsu. (舞天さん直筆メモ初公開 うるま市で来月) (Opening Exhibition of Būten’s Unpublished Handwritten Work to be Held Next Month in Uruma City]. Okinawa Taimuzu Purasu (沖縄タイムズプラス). Jan. 29. http://www.okinawatimes.co.jp/articles/-/10364 (accessed September 3, 2016).

Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence. 1998. “Okinawa: Effects of Long-Term US Military Presence: History of U.S. Military Presence.” East Asia-US Women’s Network Against Militarism. http://www.genuinesecurity.org/partners/report/Okinawa.pdf(accessed May 5, 2014).

Okinawashi shisei shikō 40 shūnen kinen jigyō: Okinawa shimin heiwa no hi kinen gyōji.(沖縄市市制施行40周年記念事業:沖縄市民平和の日記念行事) (Event Marking the 40th Anniversary of Okinawa City’s Incorporation as a Municipality: Ceremony For the Citizens of Okinawa City on Peace Day).Okinawa City Hall. 2014. http://www.city.okinawa.okinawa.jp/sp/about/1032/4223/1283(accessed August 5, 2016).

Ohana, Būten. 2002. Okinawa mandan Būten warai no sekai (沖縄漫談ブーテン笑いの世界)(Būten’s World of Comedy) Vol. 2. Audio CD. B/C Records.

Onaha, Zenkō. 1994. “Būten’s Universe.” Hard copy of a handwritten essay. Private archive (accessed September 14, 2016).

Packard, George R. 2010. “The United States-Japan Security Treaty at 50.” Foreign Affairs, February 23. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/japan/2010-03-01/united-states-japan-security-treaty-50(accessed 10/21/16).

Pérez, Laura E. 1998. “Spirit Glyphs: Reimagining Art and Artist in the Work of Chicana Tlamatinime.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 44.1 (1998): 36–76.

Piper, Adrian. 1996. Out of Order, Out of Sight Volume 1: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rakuten. 2016. Dai ikkai Okinawa shinkigeki “DO YOU Shī Mī?”(第1回おきなわ新喜劇 『DO YOU‘シーミー’?』) (Okinawa New Comedy’s First Performance, “Do You Shī Mī?”).Rakuten toraberu (Rakuten Travel]. http://travel.rakuten.co.jp/movement/okinawa/201411/(accessed April, 2016).

Roberson, James E. 2010. “Songs of War and Peace: Music and Memory in Okinawa.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 8, Issue 31, No. 3. Online: http://apjjf.org/-James-E.-Roberson/3394/article.html

Said, Edward W. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf.

Sandrow, Nahma. 1972. Surrealism: Theater, Arts, Ideas. New York: Harper & Row.

Seki, Hiroshi. 2016a. “Oka no Ippon matsu”(丘の一本松) (The Lonesome Pine on the Hill). Tarū no shimauta majimena kenkyū(たるーの島唄まじめな研究)(Tarū’s Serious Research on Island Songs). http://taru.ti-da.net/e2324577.html (accessed October 11, 2016).

———. 2016b. “Umi no chinborā” (海のチンボラー) (Little Sea Shells). Tarū no shimauta majimena kenkyū(たるーの島唄まじめな研究)(Tarū’s Serious Research on Island Songs). http://taru.ti-da.net/e598582.html (accessed October 11, 2016).

Sogabe, Tsukasa. 2006. Warau Okinawa: Uta no shima no onjin Onaha Būten (笑う沖縄: 「唄の島」の恩人・小那覇舞天伝)(Okinawa Laughs: A Biography of Būten Onaha: Savior of the “Island of Music”). Tokyo: X-Knowledge.

Takazato, Suzuyo. 2000. “Report from Okinawa: Long term military presence and violence against women,” Canadian Woman Studies (19) 4: 42-47.

Trinh, T. Minh-Ha. 2009. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1). decolonization.org. September 8. http://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/download/18630 (accessed June 2, 2016).

Ueunten, Wesley Iwao. 2012. “Descendants of the Ryūkyūan Kingdom: Okinawa Diasporic Identity Matter.” Jiangmen City, Guangdong Province, China. Unpublished paper.

Walsh, Catherine. 2014. “Pedagogical Notes from the Decolonial Cracks.” Colonial Gesture. http://hemisphericinstitute.org/hemi/en/emisferica-111-decolonial-gesture/walsh (accessed June 2, 2016).

Yoshimoto, Kōgyō Co. Ltd. 2016. Kaisha gaiyō. Yoshimoto kōgyō kabushiki gaisha (会社概要 | 吉本興業株式会社) (Company Profile: Yoshimoto Industries Co. Ltd.) http://www.yoshimoto.co.jp/corp/info/ (accessed October 15, 2016).

Yoshimoto Kōgyō Co., Ltd. 2016. Yoshimoto kōgyō hisutorī:Yoshimoto kōgyō kabushiki gaisha. (吉本興業ヒストリー|吉本興業株式会社)(The History of Yoshimoto Industries: Yoshimoto Industries Co. Ltd.) http://www.yoshimoto.co.jp/100th/history/ (accessed October 1, 2016).

Dr. Ariko S. Ikehara earned her PhD in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley in 2016, based on interdisciplinary study and research in comparative colonial and decolonial literary studies, translation studies, and performance studies. Currently, Dr. Ikehara is a Visiting Scholar in the Gender Women Studies Department at the University of California, Berkeley, and she is part of a new cutting-edge initiative called The Workshop on Blackness and the Asian Century (BASIC), founded at UC Irvine through the auspices of the UC Consortium of Black Studies in California, a multi-campus program and research initiative.

[1]Intentional or unintentional, the word “net” is double played in the second part of “JapaNet” (i.e. “net”), which is also the meaning of the second character used to write “Okinawa” (i.e. 縄). Moreover, the “net,” which is a tool to catch fish, is also a literary devise to catch a thief.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.