His sickness having taken hold of his body, his mind wandered in and out of consciousness. In high fever and debilitating pain, he could only feel an occasional thump whenever the makeshift sleigh, on which he was being carried by his comrades, stumbled over something. In the deep, snow-covered mountains of Tianqiaoling, Manchuria, neither he nor his comrades were certain whether he would live. For, they knew that not too far behind them, the Imperial Japanese Army was closing in on them. It was January of 1935, and this man, Kim Il Sung, was leading a small armed band of anti-Japanese guerillas when he fell seriously ill. They were trying to pass along this mountainous route in order to rejoin Zhou Bao-zhong’s unit in Jiandao, their Chinese comrads-in-arms. When he had set out on the expedition, Kim had fifty or sixty men. Now the unit was down to sixteen.

When the group stopped to catch its breath, Kim Il Sung learned that his favorite soldier, Wang Tae Hung, had been killed during the last skirmish with the Japanese. Overcome with sorrow, in his worsening sickness, he wept painfully. It was then that an angry thought came to him, the thought of quizzing his comrades as to whether they had buried him properly – if the tundra [soil] had been too hard to dig, at least whether they had covered his body with snow. Immediately, however, he realized that his comrades would have taken care of the soldier’s body as best as they could under the circumstances, and decided not to ask any questions: How would they have not known to do that? They, too, loved Wang. Instead, he asked his comrades whether they remembered the location at which comrade Wang had fallen. They told him that they did, and all of the men made a resolution to return one day in order to rebury Wang. But, this never happened (Kim 1992c: 415).

“Many other comrades-in-arms also lay unburied there at Tianqialing. When I recall them, I still feel my heart rending asunder. I feel I owe a debt which I can never repay. How can I express my regret?” writes Kim Il Sung (Kim 1992c: 415).

Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo(With the Century: The Memoirs), an eight-volume set containing Kim Il Sung’s memoirs, was published in Pyongyang between 1992 and 1996. Given that Kim died in July 1994 upon completion of Volume 6, Volumes 7 and 8 were published posthumously, and were based on drafts and notes that Kim had left. An English translation of the complete set is available in PDF format on North Korea’s official state website ( http://www.korea-dpr.info/lib/202.pdf). The close correspondence between the timing of Kim’s death and the publication of his memoirs is strange, to say the least, as if Kim had anticipated his death and had begun writing them a few years prior to his passing. For, right before his death, Kim Il Sung had virtually re-written his history by way of his memoirs.

What I mean is that there is an interesting twist associated with the publication of the memoirs, a twist that makes Kim Il Sung into something that was different from what he had been until 1994. By the time of his death, Kim had been elevated to the status of sacred national symbol. In dying, he acquired eternal life, having been immediately resurrected with the title of Eternal President, an office which no one, not even his son nor grandson, would assume thereafter. In something of a prosaic yet substantial counterbalance to all of this, the memoirs speak to Kim’s humanness – he depicts himself as a man, nothing more and nothing less. Reading Kim’s memoirs at this point in time, his son’s reign having come and gone and his grandson having now assumed power, gives us an interesting glimpse into how North Korea situates and envisions the position of leader vis-à-vis the people. In this article, I would like to explore an example of a shift in the position Kim Il Sung occupies in North Korea’s history (from human to deity) via a close reading of Kim’s memoirs. My strategy of doing so is two-fold: I shall try to approach memoirs with the intent of locating its authenticity on the one hand (section 1 below) and by situating myself as a “native reader” of Kim Il Sung’s words, on the other (section 2). These will be followed by the exploration of memoirs’ key points (section 3).

1. In Search of Authenticity

Kim Il Sung’s epic memoirs are remarkable in many ways, encompassing many layers of possible inquiries. Needless to say, there is more than one way to read them. Some scholars point to the factual discrepancies contained within them (Tertitskiy 2014). My interest does not lie in factual verification of the text. For any text that is produced in a propaganda-dominated society, where editorial direction and content are firmly in the hands of the state, it is expected that historical facts will be presented so as to align with a version of the truth acceptable to the regime. Does this mean, then, that the text is not authentic? Such is my question.

It has been said many times over that the authenticity of an autobiography, a memoir, or even a testimonial cannot simply be taken as given. Indeed, it is often tested, contested, scrutinized, and disputed. We see a well-known example in the controversy surrounding Rigoberta Menchú’s autobiographic life history. Published in 1982, and based on tape recordings made by Elisabeth Burgos-Debray while Menchú was in exile in Paris, I, Riberta Menchú, an Indian Woman in Guatemala immediately gripped the world’s conscience through its first-person revelations concerning the extreme violence and hardship endured by the Guatemalan people, and especially its native population, under the nation’s military government (Menchú and Burgos-Debray 1982). Rigoberta Menchú claimed that hers was the story of all of the poor Indians of Guatemala. Her story played a decisive and pivotal role in disseminating knowledge concerning the plight of the Guatemalan peasants, eventually earning her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992.

Some years later, a dissenting voice refuting Menchú’s account rose up from a rather unexpected quarter – not from the Guatemalan military, nor from the forces associated with it, but from an anthropologist. Dissecting and refuting many of the details that Menchú had presented as factual events, some of which she claimed to have witnessed personally, David Stoll argued that Menchú’s stories were simply not true. For example, contrary to Menchú’s recollection of her own brother and others tortured and burnt to death in her hometown’s main square, Stoll drew upon first-hand interviews with townspeople who told him that no one had actually been burnt alive in the town square after all (Stoll 1999: Ch.1). Stoll went on to assert that the Guatemalan picture was not as clear as the one presented by Menchú – a sharp, dichotomous conflict between government army and guerrilla forces – but instead a more complex scenario in which peasants were caught in the middle, suffering at the hands of both the army and the guerrillas (Stoll 1999).

Does this, then, make Menchú a liar? Menchú represented her political stance at the time, based on her convictions and her recollections of her own experiences. Autobiographic writings are haunted by a dilemma: while a subject may assert his or her own version of past events, others may recall these events in different and sometimes fundamentally conflicting ways. Still, in terms of truthfulness, despite the thoroughness of Stoll’s “fact-checking,” there is very little basis for concluding that the credentials of his informants carry more weight than Menchú’s, either, even if their accounts are said to have been assessed by a more careful methodology. Stoll’s work has been heavily criticized, mostly on political grounds, with Stoll responding that the “wish to create quasi-religious cults around” Menchú’s testimonio should be unmasked (e.g. Pratt 2001, Warren 2001; Stoll 2001: 120).

Against this backdrop, when reading Kim Il Sung, rather than deeming it as factually-based documentation to be judged true or false, I would like to approach it as a text that does something – as in J.L. Austin’s notion of the performative statement (Austin 1962) – rather than as a text thatsays something. As such, just as Menchú’s testimonio had a political mission, I would like to discern what the mission of these memoirs could have been. This amounts to a detour when thinking about the authenticity of this text, but the authenticity of Kim’s memoirs may lie not in their factual correctness or exactness, but in the effect or efficacy that the text creates, as I shall argue later in this article.

2. The Native Reader

Another approach that I deploy in reading Kim Il Sung rests on the fact that I am a native reader of this text. I am not saying this because Korean is my native language, but instead because I am concerned here with the content or ethos of the memoirs, a proficient knowledge of which I was made to acquire as a child during my formative years.

As readers of my books would know, I received the first sixteen years of my education in a North Korean environment in Japan, where I was born and raised. My parents were colonial immigrants from southern Korea – my father’s ancestral home is Jeju Island, and my mother’s lineage is from North Gyeongsang Province. Heightening Cold War tensions in East Asia, with Korea’s partition followed by the Korean War (1950 – 1953), combined with a strong left-wing current in Japan during the 1950s and 1960s, led the majority of progressive Koreans in Japan to support North Korea, despite the fact that, just like my parents, they traced their ancestral lineage to southern Korea. Behind such a choice lay the widespread belief that Korea’s partition would soon come to an end. This was because there was no reason that Korea (and not Japan) needed to be partitioned after World War II. Korea had not been an aggressor against the Allies during the war – to the contrary, it had been a victim of Japan’s aggression.

After the war, support for the northern regime among Koreans sojourning in Japan who originally hailed from southern parts of the peninsula stemmed from their fervent nationalism. The fact that the Soviet occupation of northern Korea led to well-known anti-Japanese Korean leaders (including Kim Il Sung) taking positions at the forefront of the newly formed regime was a decisive factor. By contrast, in southern Korea, the American Military Government relied on the remnants of the Japanese colonial establishment, allowing southern Korea to fall into a state of general discontent that was often punctuated by eruptions of violence (Cumings 1981). In 1955, following a decade of suppression by the Japanese authorities, Koreans in Japan who supported North Korea re-organized themselves under the umbrella organization, the General Association of Koreans in Japan, abbreviated in Korean as Chongryun. (I use the old italicized version of the name, as opposed to its current italicized form, Chongryon, since neither is “correct” according to the official South Korean system of Romanization. As far as I am aware, North Korea does not have a coded system of Romanization.)

Chongryun adopted an ingenuous strategy. Declaring itself a North Korean overseas organization, it thereby relinquished its demand for residential rights for Koreans in Japan, instead adopting the position that all Koreans in Japan were overseas nationals of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) that would eventually be repatriated to Korea, which would be reunified as the result of North Korean initiative. According to this definition, their stay in Japan was only a temporary one, and there was therefore no need for them to participate in activities demanding an improvement in their residential status in Japan. This measure effectively created a mutual distance between Chongryun and the Japanese authorities. One distinct effect produced by this position was the exemption of Chongryun’s education system from official academic accreditation by the Japanese education authorities. Instead, all Chongryun schools were allowed to register as vocational schools. This deprived Chongryun schools of academic legitimacy and access to the government funding. In exchange, however, Chongryun was able to maintain a curriculum that was autonomous and therefore not subject to regulation and inspection by the Japanese authorities. At the height of its strength during the 1970s and 1980s, Chongryun had a total of over 150 elementary, middle, and high schools, in addition to a four-year college and graduate programs (Ryang 1997).

As I have written elsewhere, the content of the Chongryun school curriculum was modeled after that of North Korea. It included subjects such as the Revolutionary Activities of Marshal Kim Il Sung and the Revolutionary History of Marshal Kim Il Sung. The Korean language, Korean history, and Korean geography were offered, respectively, under the rubrics of (what would be the equivalent of) Language Art, History, and Geography, with the Japanese language offered as a foreign language, and Japanese history and geography incorporated into World History and World Geography. What needs to be stressed here is that, outside of the school environment, the students and teachers were all living in Japan, speaking Japanese just like the natives, watching Japanese television, and doing the kinds of things that their Japanese cohorts would do. Indeed, culturally speaking, the majority of second and third-generation Koreans in Japan were extremely well assimilated into Japanese society (Ryang 1997). Speaking from the perspective of legal and civil rights, however, their situation was deplorable. Unlike the numerically smaller population of Koreans in Japan who supported South Korea and opted to obtain South Korean nationality (which became available from 1965 following the normalization of relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea), Chongryun Koreans had only temporary residential status, their registration needing to be renewed every three years, despite the fact that multiple generations of Koreans had been born in Japan by the 1980s.

I was a good student, academically and politically, at my Chongryun grade schools, and was given a leadership role in the Korean Young Pioneers up to middle school, and in the Korean Youth League at high school. These roles required me to faithfully read the collective works of Kim Il Sung, learning by heart his New Year’s greetings and other “teachings,” for example. One of my roles in the Young Pioneers was that of haeseolweon, meaning that I was assigned to describe (following a set script) photographic posters depicting Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary history. These were replications of identical North Korean poster sets capturing moments in Kim’s life, from his birth to his present-day glory. These posters introduced members of his lineage who were legendary fighters and leaders in Korea’s independence movement; Kim’s childhood, which was filled with stories of filial piety, good behavior, and patriotic and revolutionary spirit, and; Kim’s anti-Japanese guerrilla struggles, marked by great victories, that eventually permitted Korea to achieve its independence. These posters were displayed on red-velvet-covered walls in a special room at the school. At the front of the room was a bust of Kim Il Sung. Entering the room, we would firstly pay our respects to Kim, our right arms raised in the formal salute of the Young Pioneers. I would stand at the front of the class and recite, word-for-word, what I had memorized, pointing to the pictures with both hands deferentially raised as I moved from one picture to another.

Figure 1: Kim Il Sung’s family. Kim Il Sung as a child, his father Kim Hyong Jik holding his youngest brother Yong Ju, his younger brother Chol Ju, and his mother Kang Ban Sok. Photo courtesy of KCNA.

The type of practice mentioned above was part of North Korea’s efforts during the 1970s and 1980s to complete the establishment of a singular ideological system or yuilsasangchegye within the framework of Kim Il Sung’s Juche Ideology (see Suh 2014). When compared with today’s nuclear-crazed national rhetoric, this seems almost innocuous, but it was a serious business, most readily manifesting in the daily discursive practices of North Koreans (and, accordingly, those of us who attended North Korean schools in Japan). In workplaces, classrooms, and party cells, North Koreans were required to faultlessly quote Kim Il Sung’s words, or malsseum, during their routine (and mandatory) criticism and self-criticism sessions, or bipangwa jagibipan. Any erroneous citation would be seen as a sign of insufficient loyalty, resulting in severe criticism, and sometimes even punishment.

The same types of practice were introduced into Chongryun schools and organizations. In Young Pioneer units, children would start their daily or weekly self-reviews by quoting the words of Kim Il Sung. Any mistake would lead to drawn-out criticism by all present. It was a case of memorize or perish. Children would therefore resort to memorizing the shortest sentences possible in order to minimize the risk. In such an atmosphere, anyone who was able to quote longer passages from Kim’s works without error would be seen as a student who was better-prepared, more loyal, and therefore superior. One can easily imagine that, in more serious settings, such as during criticism sessions in party cells in North Korea proper, one mistake could result in one’s political demise.

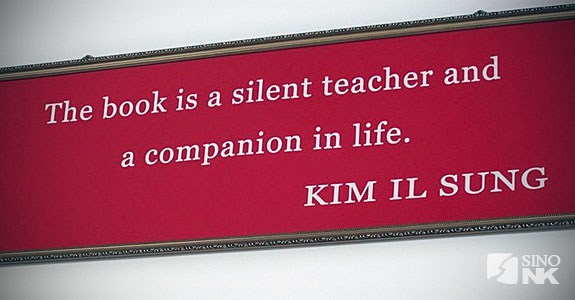

Figure 2: Kim Il Sung's words (in Korean) were hung in an identical red frame throughout Chongryun schools. Photo courtesy of Christopher Richardson.

In addition to the correct reproduction of quotes, the accurate use and reproduction of epithets, adjectives, and storylines was also important. Discursive practice, therefore, became focused on a finite set of vocabulary and expressions – as long as one could use them correctly, one would avoid trouble. By the time our high school education was over, my cohort and I were masters of fixed expressions, including: “baekjeon baekseungui gangcheolui ryeongjang“(“the legendary iron-like general who fights one hundred wars and achieves one hundred victories”) (a reference to Kim Il Sung’s military skills), “uri inminuieobeoi suryeong” (“our people’s leader who is both father and mother”) (a reference to Kim Il Sung’s endless love), and so on.

In a similar vein, in repeatedly recited stories and examples of veneration, Kim Il Sung was evoked as a perfect being who was unfailingly sagacious, virtuous, and capable of achieving anything he set his mind to. Paralleling the daily discursive practice, official referencing, news headlines, political commentaries, and literary production became standardized in the way in which they referred to the Great Leader, together transforming Kim Il Sung into something other than a man, something close to a deity. As I have argued elsewhere, in North Korean literature throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Kim undergoes a metamorphosis from mortal to abstract being. While earlier novels often quote his words and depict his appearance and facial expressions, later novels are marked by less frequent depictions of Kim in humanly form, and he is typically referred to as unprecedented love or as a shining light, for example (see Ryang 2012). From the above, we see a fixed figure of Kim emerge – a thing or a being that is – sacred, awe-inspiring incredible, and no longer human. And that is the image of Kim that native readers are familiar with. It is with this sensitivity – as a native reader – that I read his memoirs.

For a native reader such as myself, reading Kim’s memoirs is an experience that mixes the familiar and the strange. Familiar because there are episodes and events that are precise repetitions of what would be etched into the memory of any native reader, including Kim’s recollection of visiting his father in prison as a little boy after his father’s arrest by the Japanese authorities, or the story of the twelve-year-old Kim taking a solo journey home to Korea from Manchuria in order to attend the school run by his maternal grandfather. At the same time, the memoirs contain not only many hitherto-unknown stories about his family and friends, but also fine details concerning Kim’s emotions and vulnerability that no novel, government publication, or publication by Kim himself (including official speeches or political writings) has ever conveyed, making the Kim in the memoirs a stranger to the native reader.

Along with Kim’s conspicuous imperfections, the image of Kim that emerges from the pages of his memoirs is one that is far from that of an abstract being – he is depicted as a kind, strong, warm, vulnerable, uncertain, and, above all, honest man. In his memoirs, Kim is not a general who fights one hundred wars and achieves one hundred victories, not an all-knowing, all-sagacious, wise man, and not a strong and great man, his heart sustained by unfailing conviction and an iron will. At times, Kim is emotional, remorseful, and self-doubting. He makes errors, and admits to doing so, he acknowledges his own petty suspicions and wrong judgments, and he weeps, cries, wails, and loses direction – in other words, he is very, very human. If we are to accept, at a minimum, that historical texts such as memoirs that depict the lives of particular individuals do different things with respect to factual forms of documentation, whether they be retrospective attempts to capture the spirit of the past or introspective reconstructions of the past that reflect today’s perspective – thereby informing the reader more about the present than the past itself – then my native reading of Kim Il Sung’s memoirs is not carried out with the intention of refuting Kim’s words on a true-or-false basis. In this regard, it differs from Stoll’s efforts. Rather, my strategy is to excavate humanity from within Kim’s words, words written by a man who died as a deity for North Korea and who lives on (forever) as its Eternal Great Leader, exploring what these words do with respect to the relationship between Kim Il Sung and his people.

3. All Too Human

A. Youth and inexperience

By 1930, when he was eighteen years old, Kim Il Sung had already formed the conviction that the only way that he could help Korea regain its sovereignty from Japan would be for him to join the armed guerrilla struggle. Independence-minded Korean men and women had already organized themselves into armed units in eastern Manchuria which was referred to as Gando in Korean (Jiandao in Chinese) – meaning the land in between (China, Korea, and the Soviet Union), bearing diverse nomenclature in the immediate aftermath of Japan’s formal annexation of Korea in 1910, if not before. In history-related writings, as well as in Kim’s memoirs, these units are normally grouped under the collective term, dongripgun, or independence army. Some of these units were officially affiliated with the Provisional Korean Government in Exile that was proclaimed in Shanghai following the 1919 anti-Japanese uprising on the peninsula, while others were sporadic and voluntary groupings of men and women committed to Korea’s independence, each with more or less ties with Chinese anti-Japanese armed groups in Manchuria. By and large, they were governed by the Confucian ethos of ui, or righteousness. This does not mean that all of the units were dominated by age-based seniority or lineage-based unity. This ethos was manifested in the way in which anyone who had a sense of ui felt impelled to join the fight to rectify the wrongs done to Korea by the Japanese. Thus, men and women, old and young, joined in the armed resistance. They were active in Manchuria, rather than in Korea proper, because the thoroughness of police surveillance on the peninsula made it impossible for such activities to be organized and sustained there, forcing many into exile in order to form resistance forces. Despite sharing a common desire to defeat Japan, the armed independence-minded groups did not always enjoy a cooperative relationship with each other, sometimes engaging in serious confrontation. It would also be safe to say that all of them were skeptical of the new ideology, Communism.

Separate from these earlier generations of anti-Japanese fighters, Kim was seeking to build a form of armed resistance with a Communist identification – not unusual for Korean diasporic youth in Jiandao during those days. This did not mean that Kim was hostile to earlier generations of independence fighters; in fact, he was quite deferential and reconciliatory toward the older generation, consistently maintaining respect in light of the fact that many members of this generation were close allies of his deceased father. But he also felt that the older generations were missing the mark by not embracing the new ideology, Communism, and that they were entrenched in a premodern idea concerning the national sovereign that did not align with concepts such as democratic government and equality for all.

Figure 3: Map of Jiandao. In Korean, it was referred to as Gando, literally meaning the land in between. Kim’s anti-Japanese guerrilla activities were mainly waged in East Gando on the map. Courtesy of Korea Times.

Everything that we have covered up to this point aligns with the memories of the native reader – how the young Kim was attracted to Communism in his search for a new way to regain independence for Korea. What follows, however, is a hitherto-unnoticed point: Kim recalls how naïve he was at the time, saying, “We had only patriotism and young blood,” and thought that if he and his group were to wage armed resistance, they would be able to defeat the Japanese Imperial Army in three to four years, an idea that he wryly qualifies by saying, “If the Japanese warlords had heard of this, they would surely have thrown their heads back and burst out laughing (angcheon daeso)” (Kim 1992b: 44; translation original). This is a deviation from the official representation of Kim’s revolutionary history, which maintains that Kim’s revolutionary journey was consistently guided by scientific methodology and correct vision from the very outset. If anyone were to depict the young Kim as naïve at any of the Chongryun schools, this would have incurred wrath.

Kim’s own recollections of his interactions with the older independence fighters show a man of flexibility - sometimes compromising, sometimes frustrated, but altogether not so stubborn, willing to talk with others rather than alienate them. In the official North Korean version of Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary history, he is depicted as having lofty virtue and poongryeok, the ability to be inclusive and reach out to others, including elders. What is newly presented in the memoirs is how he does it. In contrast with the image of Kim presented in the official history, that of a sagacious young man whose overwhelming wisdom led to his age becoming instantaneously irrelevant to older and more experienced people, the memoirs have Kim himself detailing how he would maintain a consciously humble stance when approaching the elders, receivingbanmal or the speaking-down form of speech from the eolders and presenting his own views to them only where appropriate etiquette-wise, an approach altogether not in conflict with the Confucianist order of things.

Figure 4: Kim Il Sung at the time he attended Jilin Yuwen Middle School. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

B. Sinophilia

In a similar vein to the above, the young Kim is full of admiration for his elders and teachers. Especially touching is his deep respect and love for his literature teacher at Jilin Yuwen Middle School, Shang Yue, or Sang Wol in Korean. A member of the Chinese Communist Party, Shang introduced Kim to Chinese classics, including Dream of the Red Chamber, as well as works by contemporary progressive Chinese and Russian writers, such as Maxim Gorky, while teaching at Yuwen in 1928. It was through him that Kim Il Sung became attracted to Communism, began reading Marx and Lenin in Chinese, and was exposed to the avant-garde European novels of the day. This is one of the many Chinese connections detailed by Kim in his memoirs, alluding to the fact that he was not, after all, the autochtonous product of Korea, as depicted in his official revolutionary history, but an individual whose formative ideas were rooted in Manchurian soil through shared experiences and close collaboration with the Chinese Communists. Forever indebted to Shang, Kim welcomed Shang’s two daughters to North Korea, in 1989 and 1990 respectively. He concludes his chapter on Shang Yue with the statement: “He who has had a teacher to remember for his lifetime is a lucky man. In this regard, I am a lucky man. When I miss Master Sang Wol, who left an indelible mark on me during my formative years, I go back to Yukmun [Yuewen] Middle School and walk its campus in my mind. I miss Master Sang Wol very much (Kim 1992a: 235).”

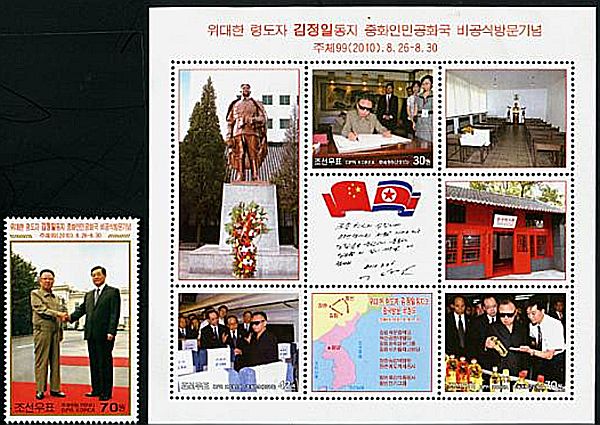

Figure 5: This official photos of Kim Jong Il’s visit to China shows, second from the left, top, Kim Il Sung’s statue built on the ground of today’s Jilin Yuwen High School. Courtesy of KCNA.

One of the individuals to whom Kim devotes a large number of pages in his memoirs is Zhang Wei-hua, his childhood friend from Fusong, north of the border. Zhang Wei-hua and Kim Il Sung enjoyed a special relationship that began during their childhood. This was despite the fact that Zhang came from a family of enormous wealth, while Kim was the son of poor immigrants. After Kim joined the guerrilla army, Zhang wanted to join him, personally begging Kim to take him along. Kim refused out of love, as he knew that joining the guerrillas would place Zhang’s life in serious danger. Instead, Kim asked Zhang to support him from behind enemy lines (Kim 1993: 417-418). Zhang operated a photographic studio at the time, and Kim asked him to use his position and network to engage in information-gathering. Eventually, the Japanese authorities found out about Zhang’s connection with Kim, arresting him for interrogation. Zhang’s father managed to bail him out. Knowing that another interrogation session was imminent and worried that he might not be able to withstand the torture next time around, Zhang took his own life. This incident tormented Kim for the rest of his life. Many decades later, he built a monument to Zhang with his own Chinese inscription. He also invited Zhang’s children and grandchildren to Pyongyang many times, welcoming them as state guests (Kim 1993: 385ff, 419ff).

Despite one of Kim Il Sung’s epithets being jeolseui aegukja (the unprecedented patriot), it is undeniable that he had a deep love for China – its history, culture, language, and people. It could of course be claimed, therefore, that love of Korean culture and love of Chinese culture need not be mutually exclusive. Nevertheless, official North Korean representations of Kim Il Sung do not allow room for such an interpretation, his Sinophilia very much suppressed. Back in 1935, in an effort to break the ice with the local Chinese residents while attempting to penetrate the village of Emu on Lake Jingbo in today’s Heilongjiang Province, Kim’s group performed Su Wu Mu Yang (Su Wu Tends Sheep), a song about Su Wu (BC 140-60), a Han Dynasty diplomat who spent nineteen years in captivity in a foreign land. Despite his extended incarceration and the various hardships that he suffered while in exile, he never abandoned his loyalty for the homeland. While carrying out this propaganda initiative, Kim was deeply moved by the song himself, recalling:

“My experience at the Chinese village [of Emu] on Lake Jingbo was so emotional that I tried in various ways after the liberation [of Korea] to find the text of the Su Wu song. It was only recently that I was able to obtain the text in Chinese (…) I was so pleased that I sang the song [again], forgetting that I was already in my eighties. How well could a man of eighty sing? (…) [T]he fresh memory of my youthful days, which had vanished far beyond the clouds, welled up in my mind, together with my deep attachment to the soil of northern Manchuria, where we had pioneered the revolution with such difficulty. Whenever I yearn for those days, I play this song on the organ. Sometimes I try to whistle it, but the sound is not as fresh as when I was in my twenties (…)” (1993: 189).

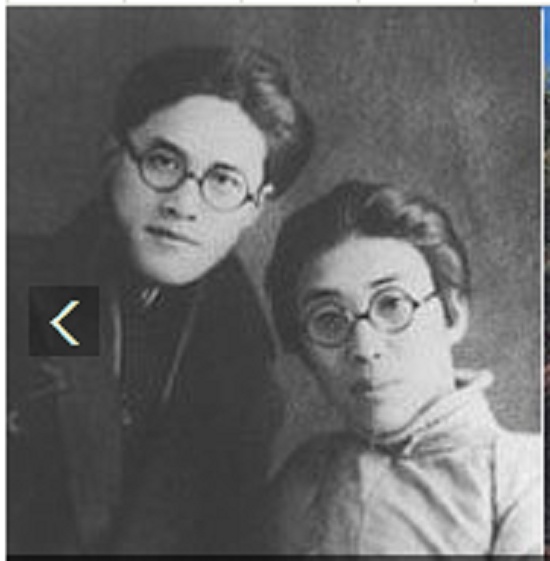

Figure 6: Zhang Wei-hua and Chol Ju, Kim Il Sung’s younger brother. Photo courtesy of Best China News.

Lake Jingbo provides Kim with another recollection. It was on the edge of this lake that he heard the news of his younger brother Chol Ju’s death. Chol Ju was killed in an armed skirmish near Chechangzi in June 1935. And it is because of this that Kim thinks about his younger brother whenever he sees a large river or a lake, according to his memoirs (Kim 1992b: 433). The photograph of Chol Ju included in official North Korean portrait collections captures a young man sporting a stylish pair of eyeglasses, his hair combed back, dressed in a Chinese suit. It is very possible that Zhang fitted these for Chol Ju who lived in utter poverty. As far as I can tell, this is the only existing photograph of him. The original photograph was taken with Zhang Wei-hua, who has an identical hairstyle and suit and is wearing an identical pair of glasses, alluding to the closeness between the two men. He was barely twenty years old when he died, and therefore little is known about him, save for a mention in the official English version of Kim’s memoirs that Chol Ju served with a “Chiang Kai Sek guerrilla unit” and was killed in action. This information is not mentioned anywhere in the Korean version. I have tried to identify the “Chiang Kai Sek” that is referred to here. While the spelling is similar to that of Chiang Kai-shek, it is not identical. If, however, this is indeed a reference to Chiang Kai-shek, it would cast some doubt on Chol Ju’s commitment to Communism which is, again, depicted in the North Korean official version of Kim Il Sung’s family history; Chiang strenuously refused to collaborate with Mao until 1936, devoting more effort to defeating the Communists than the Japanese.

While Zhang makes occasional appearances in the official North Korean revolutionary history of Kim Il Sung, certain personal and geographic names, such as Shang Yue (Sang Wol), Su Wu, Lake Jingbo, and the village of Emu, are introduced for the first time, as are references to the fact that Kim was an avid reader of Chinese and other foreign classics and literary works. Although the official history does not fail to mention that Kim was a fluent speaker of Chinese, the extent to which he was versed in Chinese, immersed in China’s culture, and emotionally linked to his Chinese friends and teachers comes as a surprise to the native reader.

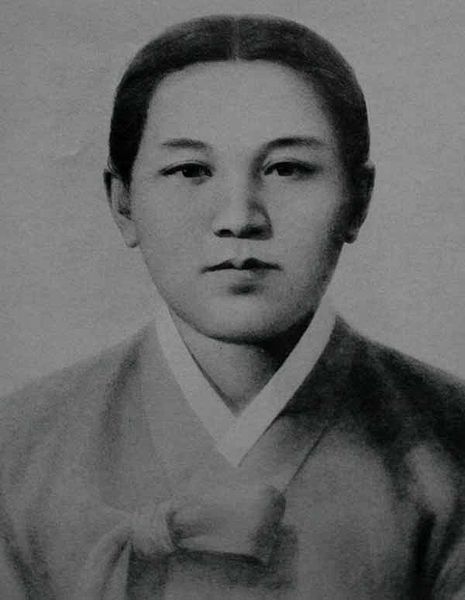

C. Mother

Recollections by Kim concerning his love of his mother and his longing for her extend over many pages and chapters of his memoirs. His mother, Kang Ban Sok, was born to a Christian family that enjoyed a relatively high standard of living, as well as local respect for the missionary school that it operated, Changdeok Elementary School. Kim himself attended this school for a few years, having been sent back alone to Korea at the age of twelve after his family was exiled to Manchuria. He studied there under his maternal grandfather, a devout Christian, until called back to Manchuria due to his father’s worsening health. His mother was a religious woman – references to her attending church services would seem to remove any doubt. According to Kim, she was a woman of conviction and strong will, her love deep and genuine. She married Kim’s father, two years her junior, at the age of eighteen. Kim Hyong Jik (Kim Il Sung’s father) was studying at Pyongyang’s top missionary school at the time of their marriage.

It is striking then, to see that despite having grown up in relatively fortunate economic circumstances, by which I mean that her family ran a school, her father and brothers were highly educated by the standards of the day, and, as far as one can detect, she was not sent out to work as a maid or farmhand in order to earn extra income for the family, Kim’s mother endured extreme poverty and hardship after her marriage, especially after the passing of her husband in 1926 at the age of only thirty-two. This led her to suffer chronic ill health, which eventually led to her death at the age of forty. Due to a shortage of income and in search of cheaper rent, she had to move the family frequently. A photo of the lonely cottage in Xiaoshahe where she finally passed away illustrates the starkness of the family’s everyday circumstances.

Figure 7: Kang Ban Sok, Kim Il Sung’s mother. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Recalling his mother in his memoirs, Kim often drifts into introspective musings concerning the challenges faced when striving to reconcile love of family and love of nation (e.g. Kim 1992b: 207). But, whenever he was inclined to show concern about household affairs – Kim was, after all, head of the household after the passing of his father, according to Korean tradition – his mother would proactively warn him not to bother himself with such matters. Nevertheless, Kim continued to agonize over how to strike a balance between his commitment to the guerrilla struggle and his devotion to his mother, especially after her illness took a more serious turn. In 1932, soon after forming a guerrilla group, Kim paid his mother a visit, traveling on foot and carrying a bushel of rice on his back. During this visit, Kim was gripped by deep hesitation and self-doubt. He mused whether he should put off the armed struggle for a while and continue his underground activities for a few more years in order to be able to support his mother and visit her often – would this be the right thing for an eldest son to do? (Kim 1992b: 381). Reading this passage, the native reader is caught by utter surprise. While the official North Korean version of the nation’s history presents Kim’s founding of the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army in 1932 as solid fact, the memoirs offer a sharp contrast from this representation, showing Kim to be full of hesitation even after establishing the guerrilla group, musing over the possibility of returning to his underground activities. Bidding his mother farewell as he leaves, he lingered at the front of her house, his concern for her wellbeing momentarily preventing him from taking one more step away from her. His mother, now back inside the house, swang the door open and scolded him severely: “How can a man who has committed himself to the cause of winning his country back continue to have such a weak heart and worry about his home? (…) If, in the future, you were ever to come home because you were anxious about your mother (…) I wouldn’t meet that kind of son!” (Kim 1992b: 337).

In the fall of 1933, having won a few successful battles against the Japanese and despite his mother’s admonition a year earlier, Kim decided to pay another visit to his mother. His unit had decided to move to Wanqing, located quite a distance from Jilin, and he wanted to bid his mother farewell prior to a long absence. He brought along a few packets of herbal medicine. Approaching the cottage, he had a strange feeling. His mother would normally recognize his footsteps and open the door. This time, however, no one opened it. Inside, he saw that his mother’s bed was gone. His two brothers came into the house, breaking into tears and asking him why he had not come sooner. As the three brothers wept aloud in their grief, a neighbor, Mrs. Kim, came in and told Kim about the final days of his mother. She had taken care of Kim’s mother, staying with her until her final breath. Kim recalled how Mrs. Kim’s voice sounded like a voice from heaven or a celestial land (Kim 1992b: 421). Mrs. Kim told him that, toward the end, unable to move and completely incapacitated, Kim’s mother had asked Mrs. Kim to cut her hair short – a very unusual and almost unthinkable request for a Korean woman at that time – because she had not been able to wash it for such a long time and her head was too itchy (as it was likely to have been infested with lice). As soon as Kim heard this, he regretted that Mrs. Kim had told him: “It would have been better if I had not heard this story from her. I felt that my mother’s final, sad moments were tearing me apart inside” (Kim 1992b: 422). Later, paying a visit to his mother’s grave, he saw Chol Ju quietly burying the packets of medicine that Kim had brought along with him – as if to say that their mother might still be able to make use of them after her passing over to the other side. Kim completely broke down at this sight, wailing aloud for hours (Kim 1992b: 424).

Official North Korean records refer to Kang Ban Sok as the Mother of Korea – not simply as the mother of her own three sons, but as the person responsible, through her support for Kim, for the birth of an independent Korea. In Kim’s recollections, this image of Kang – as a strong-willed individual – sits alongside another, in which she shows devotion to her son’s cause. This devotion is not one derived from her being a revolutionary or a Communist, but instead from her devotion as a mother helping her son to achieve his mission. According to Confucian practices, Kim would have inherited the family lineage from Hyong Jik, his father, as the latter’s first-born son. In this regard, his mother was doing something that all pre-modern Korean mothers were expected to do. But Kim also provides a clear illustration of a woman fighting for life in the face of poverty, hunger, and widowhood. Similarly, Kim’s mourning for his mother is heartwrenching and very personal, filled with remorse and regret, at times reducing him to an emotional wreck. This is far from the image contained in official North Korean accounts, which portray Kim smoothly and heroically sacrificing everything, including his own family, in his quest for Korea’s liberation. The raw emotion recalled by Kim in his memoirs is something new to readers, leading them empathize with him and feel closer to him as a person.

D. Religion

As for Kim’s political stance, his memoirs encompass a bundle of ecclesiastic beliefs and principles - or a lack thereof. He had a particular interest in religion, and had close friends who professed a variety of religious beliefs. Given his markedly Christianized family background, it is understandable that Kim befriended religious figures. To any native reader of North Korea’s revolutionary history, however, the fact that Kim was a regular member of a Korean congregation in Jilin comes as a surprise. His church was led by Reverend Son Jung Doh, a widely respected minister, whom Kim followed as a mentor. Reverend Son was a prominent leader among Korean expatriates in Manchuria, and had strong connections with leaders inside Korea’s independence movement, including Ahn Chang Ho. Kim was overcome with feelings of sorrow and loss when he heard the news of Reverend Son’s death (Kim 1992b: 8). Reverend Son had a special place in his heart, and Kim documented in detail a visit to him in 1991 by Reverend Son’s son, Dr. Son Won Tae, from Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Son from Nebraska asked Kim whether he would buy him bingtanghulu, a traditional Chinese candied fruit snack, just like back in the olden days in Jilin. Kim wrote: “I felt my heart leap at his request, for this was a request one made only to one’s own brother” (Kim 1992b: 13). In North Korea’s official verbiage, this kind of non-Communist connection is swept under the rug of Kim’s outstanding virtue or unprecedented broad-mindedness. In his memoirs, however, his reunion with Dr. Son is simply one of old friends who shared their childhood in exile away from their homeland. And the fact that Reverend Son was a moral mentor and father figure to Kim who, at the young age of sixteen, lost his own father, played a significant role in the formation of such a bond, a personal connection to a religious figure altogether omitted in North Korea’s official version of Kim’s revolutionary history. Thus, the following statement of Kim in the memoirs surprises many native readers such as myself: “I see no contradiction between the Christian doctrine of ‘peace on earth and good will for all mankind’ and my ‘Juche’ doctrine of self-determination for all mankind (Kim 1992a: 104).”

E. Not the best or the singular

Kim is frank when it comes to his relative standing as a guerrilla commander among many who are either similar or superior to him. In fact, he candidly depicts his as being a small group when compared to many other similar armed guerrilla units. This is a notable diversion from North Korea’s official revolutionary history, in which Kim is positioned at the apex of the Korean anti-Japanese guerilla movement, unparalleled in influence and authority. Indeed, his memoirs make frequent references to coexisting armed groups with a diverse range of political orientations that operated across the vast Manchurian wilderness – some adamantly nationalistic and anti-Communist, others directly connected with the Chinese Communist Party. Kim also frankly describes how the relative youth of the members of his unit made it necessary for it to collaborate with other units. These included notable armed Korean units, such as Commander Yang Se Bong’s Korean Independence Army (with its connection to the Provisional Government in Exile in Shanghai), another armed group led by Li Hong Gwang and Li Dong Gwang (both Communists), as well as many Chinese armed units, including the National Salvation Army led by Commander Wu Yi-cheng, and the self-defense army led by Tang Ju-wu (Kim 1992b: 303ff; Kim 1992c: 165ff). The battle of Dongning County in 1933, a famed battle that Kim’s revolutionary history boasts as a large-scale victory by the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army (Kim Il Sung’s guerrillas), was, in fact, a battle fought alongside a diverse range of Chinese nationalist forces, and in the memoirs, Kim has no problem recounting every detail of it as such (Kim 1992c: 187ff).

In February of 1935, a conference was called in Dahuangwai to review and assess the worsening situation involving mutual Chinese and Korean suspicions concerning the pro-Japanese organization, Minsaengdan. Rumor at the time had it that over seventy percent of the Korean Communists in Eastern Manchuria were secretly members of Minsaengdan. During the early 1930s, the Chinese Communist Party had purged thousands of Korean Communists under the suspicion that they were secretly connected with the Japanese. By 1935, mutual suspicion had resulted in numerous brutal cases of ethnic persecution and inter-ethnic violence. In 1933, Kim himself was arrested by the Chinese Communist Party, only to be exonerated in 1934 (Armstrong 2003: 30). Kim participated in the Dahuangwai conference in his capacity as a member of the East Manchuria Special District Party Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (Kim 1993: 46). Despite the personal persecution that he had suffered at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party, he remained loyal to the party and the cause.

Korea did not have its own Communist Party. To be more precise, Korea’s status as a Japanese colony meant that Korean Communists could not have their own party, due to the Comintern policy of recognizing only one party per nation. Accordingly, those who were in China joined the Chinese Communist Party and those who were in Japan joined the Japanese Communist Party (which was suppressed by the mid-1930s). It is likely that he joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union later on, during the 1940s, when he relocated there and became a Korean guerrilla commander under the Soviet military. The official line maintained by the North Korean historiography is that Kim formed his own Korean party – in fact, he alludes to this in his memoirs (Kim 1992b: 54ff) – but a more accurate description would be that he was an international-minded Communist with a keen desire to help Korea regain its independence, holding full membership within the Chinese Communist Party. Nowhere in North Korea’s official history would represent Kim Il Sung as a member of the Chinese Communist Party: a reading of the memoirs fully attests to this, Kim’s own words providing unmistakable acknowledgement.

4. Re-Humanizing Kim Il Sung

The knowledge that Kim was a member of the Chinese Communist Party, or that he went to the Soviet Union during the early 1940s along with other Sino-Korean guerrillas fighting in Jiandao, was widely accessible prior to the publication of the memoirs through sources published outside North Korea. Examples include Dae-Sook Suh’s depiction of Kim’s guerrilla days in Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader (1988). But read the memoirs from the perspective of a “native reader,” one immersed in North Korea’s official rhetoric, with its rules and regularities, its set expressions and storylines – and I am not problematizing or inquiring into whether the native reader is a believer or not – and the conspicuous discrepancy that is brought up to the surface by none other than Kim himself is, quite simply, shocking.

Kim’s words undo the work performed by North Korea’s state-wide Juche-oriented public discourse during the 1970s and 1980s in turning Kim into a sacred and untouchable being – a kind of deity. Such efforts were accompanied by the ubiquitous appearance of gilded statues of the leader, the largest of which was erected in Pyongyang. It was during these decades that North Korea institutionalized the practice of requiring all citizens to wear Kim Il Sung portrait badges on their chests. These measures created the effect of literally planting Kim within every citizen’s heart, at the same time generating an ethos and lifestyle that placed Kim within the domain of the unreachable and the unattainable. He was everywhere and in everyone’s soul, yet not a concrete human being. As contradictory as this may sound, the 1970s and 1980s made Kim Il Sung into a kind of sacred being, one that endlessly loves all North Koreans (and who must be loved by all North Koreans in return), one whose superhumanly wisdom and sagacity would lead North Korea to ongoing success. In bringing himself back to the ranks of humanity, the words of Kim in his memoirs free him from the domain of the unreachable or unattainable. Indeed, the memoirs make Kim Il Sung utterly relatable due to their words of candor and straightforwardness.

Speaking from a functionalist perspective, efforts such as these to humanize Kim Il Sung were no doubt necessary, given the looming succession by his mortal son, Kim Jong Il, and later by his mortal grandson, Kim Jong Un. In passim in the memoirs, Kim Jong Il is credited as having continued, elevated, and perfected the endeavors that Kim Il Sung started in his youth. Such references are most prominent in the field of artistic production. For example, the memoirs have it that Kim Il Sung himself wrote the script of a play, Hyeolhae (sea of blood, in Chinese characters) in the 1930s, which, under the leadership of Kim Jong Il, became the 1970s North Korean classic film,Pibada (sea of blood, enunciated in Korean, i.e. non-Sinicized, words) (Kim 1994: 62).

Can we, then, claim that the imperfections of Kim Il Sung that are depicted in his own words in the memoirs make this work authentic, in that it achieves the genuine political goal of legitimizing the succession or, indeed, legitimizing the entire lineage, thereby ensuring that Kim Jong Il’s offspring will succeed Kim Jong Il, and Kim Jong Un’s offspring will succeed Kim Jong Un? What better way to do this than to let the god fall rather than having to keep elevating mortals of subsequent generation to the status of deities? For, unlike his father, Kim Jong Il did not follow a personal trajectory involving substantial sacrifice for the North Korean nation. By connecting Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, and eventually Kim Jong Un, the memoirs lay out a blueprint for a revolutionary lineage. In this regard, in proving his own humanity, Kim Il Sung’s words make him and his off-springs newly authentic.

Upon Kim Jong Il’s death in 2011, I predicted that North Korea would treat Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il differently. I was mistaken: North Korea produced gold statues of Kim Jong Il, placing them right next to each and every one of his fathers’ statues. His embalmed body is now on display in the “hall of immortality” along with the body of his father at Kumsusan Palace of the Sun, a Kim family mausoleum that has become a destination for domestic and foreign visitors to Pyongyang. Every year starts with Kim Jong Un offering New Year’s greetings to both “in humble reverence” (“Kim Jong Un Visits Kumsusan Palace of Sun” 2016). The North Korean leadership, in other words, is not – contrary to an oft-abused term – based on a cult of personality. Rather, it is based on lineage, and whether or not this amounts to a cult warrants further exploration.

This notion of lineage is not, however, to be equated with lineage in the Confucian sense. According to Confucian principles, it is the first-born male who should succeed his father, but it is Kim Jong Un, the youngest son, who is now in power, and who recently managed to eliminate the first-born, Kim Jong Nam, in Malaysia (Paddock and Choe 2017). The concept of lineage practiced in North Korea today is an entirely new one. As seen in references to the blood of Paekdu Mountain (baekdusan hyeoltong), Kim’s lineage is said to have sprung from Mt. Paekdu. In his memoirs, Kim Il Sung describes his group moving its base to Mt. Paekdu, although it is hard to establish this by means of historiography: it is most commonly thought that his guerilla routes were located around Jiandao, to the northeast of Mt. Paekdu, later shifting further northeast to the Khabarovsk area. Kim Jong Il was born in the Soviet Union. According to the official North Korean rhetoric, however, Kim Jong Il was supposedly born somewhere on Mt. Paekdu. For this reason, Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla war needed to have taken place on that mountain. As is usually the case, legends involving heroes are born post factum. It remains to be seen what kind of new myths will surround Kim Jong Un, whose mother was born and raised in Japan, who was educated abroad, and whose sibling continues to live abroad, frequently attending Eric Clapton concerts (Pearson 2017).

Figure 8: Mt. Paekdu (Paektu) and its mountaintop lake, Chonji. Photo courtesy of DPR Korea Tourism.

As clearly stated by Kim Il Sung himself, the Kims originated from Jeolla Province in southern Korea. The Paekdu lineage, therefore, marks the beginning of what might be called the “new Kims.” Another parallel development in North Korea connected with the rise of the Paekdu lineage is the new identification of its people as janggunnim shiksol, or the family of the General (e.g. Shim 2013: 86), “General” being a title shared by all three Kims. We have here an intersection between a vertical relationship based on lineage and a horizontal relationship based on people/family, meaning that all North Koreans are brothers and sisters connected to and through the Paekdu lineage. Nothing could be stranger from the perspective of traditional Confucian principles, where one has to remain loyal to one’s lord on the one hand and one’s ancestors on the other since these two lines do not meet (the only exception being the King’s lineage), where an innate tension is created between loyalty to one’s lord and devotion to one’s ancestors. Kim’s memoirs perform a kind of magic in turning the Kims from southern Korea into the Kims of Paekdu Mountain, taking along all North Koreans as family members. The intimacy produced by the first person narrative of the memoirs performs this magic brilliantly, talking to readers individually, bringing them closer to Kim Il Sung the man, and arousing in them a warm fondness and affection for him. By posthumously becoming Eternal President of North Korea – thereby achieving eternal life – as well as by leaving a very human account of himself, Kim Il Sung has successfully secured long-lasting leadership for his lineage by creating a dual morphology – as god and man at the same time.

The author wishes to thank the US National Science Foundation for its senior grant (Proposal ID BCS-1357027) which facilitated archival and ethnographic research toward this article. This article is part of the book manuscript the author is preparing under the provisional title, The Anthropology of North Korea.

References

Armstrong, Charles. 2003. The North Korean Revolution: 1945-1950. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Austin, J.L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cumings, Bruce. 1981. The Origins of the Korean War, vol. 1, Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kim, Il Sung. 1992a. Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo (With the Century: The Memoirs), Vol. 1, Pyongyang: Joseon Rodongdang Chulpansa (The Workers’ Party of Korea Press).

Kim, Il Sung. 1992b. Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo (With the Century: The Memoirs), Vol. 2, Pyongyang: Joseon Rodongdang Chulpansa (The Workers’ Party of Korea Press).

Kim, Il Sung. 1992c. Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo (With the Century: The Memoirs), Vol. 3, Pyongyang: Joseon Rodongdang Chulpansa (The Workers’ Party of Korea Press).

Kim, Il Sung. 1993. Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo (With the Century: The Memoirs), Vol. 4, Pyongyang: Joseon Rodongdang Chulpansa (The Workers’ Party of Korea Press).

Kim, Il Sung. 1994. Hoegorok: Segiwa deobureo (With the Century: The Memoirs), Vol. 5, Pyongyang: Joseon Rodongdang Chulpansa (The Workers’ Party of Korea Press).

“Kim Jong Un Visits Kumsusan Palace of Sun.” 2016. Rodong sinmunJanuary 2, 2016.

Menchú, Rigoberta and Burgos-Debray, Elisabeth. 1982. I, Rigoberta Menchú, an Indian Woman in Guatemala. London: Verso.

Paddock, Richard and Choe, Sang-Hun. 2017. “The Kim Jong-nam’s Death: A Geopolitical Whodunit,” New York Times February 22, 2017. Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/world/asia/kim-jong-nam-assassination-korea-malaysia.html?_r=0 (accessed August 1, 2017).

Pearson, James. 2017. “Wonderful Tonight: Taking Kim Jong Un’s Brother to a Clapton Concert.” Reuters World News February 3,2017. Online: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-defector-kim-clapton-idUSKBN15I132 (accessed August 1, 2017).

Pratt, Mary Louise. 2001. “I Rigoberta Menchú and the “Culture Wars.”” In Arturo Arias ed., Rigoberta Menchú Controversy, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ryang, Sonia. 1997. North Koreans in Japan: Language, Ideology, and Identity. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ryang, Sonia. 2012. Reading North Korea: An Ethnological inquiry. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shim, David. 2013. Visual Politics and North Korea: Seeing Is Believing. London: Routledge.

Stoll, David. 1999. Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Stoll. David. 2001. “David Stoll Breaks the Silence.” In Arturo Arias ed., The Rigoberta Menchú Controversy, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Suh, Dae-Sook. 1988. Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader.New York: Columbia University Press.

Suh, Jae-Jung, ed. 2014. The Origins of North Korea’s Juche: Colonialism, War, and Development.Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Tertitskiy, Fyodor. 2014. “North Korean History through the Lens of Soviet Power,” DailyNK 2014. Online: http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?num=12194&cataId=nk03600 (retrieved on July 4, 2017).

Warren, Kay. 2001. “Telling Truths: Taking David Stoll and Rigoberta Menchú Exposé Seriously.” In Arturo Arias ed., The Rigoberta Menchú Controversy, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Sonia Ryang is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Professor of Asian Studies and the Director of the Chao Center for Asian Studies, Rice University. Her publications include Eating Korean in America: Gastronomic Ethnography of Authenticity (University of Hawaii Press, 2015) and Reading North Korea: An Ethnological Inquiry (Harvard University Press, 2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.