I. Introduction

In his book, Mapping China and Managing the World, Richard J. Smith offers an explanation for the “staying power of divination in China,” which “both embodied and reflected many of the most fundamental features of traditional Chinese civilization.” Although it always had a certain heterodox potential, divination “was not fundamentally a countercultural phenomenon.” Rather, enjoying abundant classical sanction and an extremely long history, “Chinese mantic practices followed the main contours of traditional Chinese thought.” [2]

This article aims to add support to Smith’s argument, albeit from a perspective that fluidly trespasses the boundaries between the “heterodox potential” of divination and the “main contours of traditional Chinese thought.” Through examining mantic practices and theories recorded in a specific group of literary texts, this article argues that divination was a significant, if not indispensable, component in the self-fashioning of certain iconoclastic intellectuals, men and women, from the Wei-Jin 魏晉 (220–420) period to the late Qing 清 (1644–1911) dynasty in China, and from the Heian 平安 (794–1185) period to the Edo 江户/Tokugawa 徳川 (1603–1868) period in Japan.

This body of literature includes the famous Chinese literary work known as the Shishuo xinyu 世說新語 (conventionally translated as A New Account of Tales of the World, hereafterShishuo), compiled by the Liu-Song 劉宋 (420–479) prince Liu Yiqing 劉義慶 (403–444) and his staff, as well as later imitations of the Shishuo in both China and Japan – a total of thirty-seven separate items in my collection. Together they are known as Shishuo ti 世說體 (the Shishuo genre).

My article explores this rich archive of literature, written in classical Chinese (also known as the literary Sinitic), [3] from the following three viewpoints: First, it identifies divination as a coherent and enduring aspect of renlun jianshi 人倫鑑識 (judgment and recognition of human [character] types, more succinctly translated as “character appraisal”), a major Wei-Jin intellectual practice that recognized and evaluated human character types and socio-political situations. Second, it examines the profusion of divinatory methods over time (from the Wei-Jin to the late Qing) and across space (China and Japan) that appear in Shishuoti works, showing how they were configured and reconfigured under certain specific social, political, and intellectual circumstances. Third, taking an explicitly gender-focused approach, this article evaluates women’s roles in mantic practices and the significance of their participation in the divinatory traditions of China and Japan.

II. Divination and Character Appraisal in China

The Shishuo xinyu records the surprisingly freewheeling social and intellectual life of Wei-Jin China by means of a great many short and extremely colorful anecdotes. By characterizing and categorizing diverse Wei-Jin personalities, this sui-generis work grew out of, and in turn registered, the practice of character appraisal – a major intellectual activity identified with the Wei-Jin ideology known as Abstruse Learning (Xuanxue玄學, a.k.a. Mysterious Learning or Dark Learning). [4] According to the esteemed Sinologist Erik Zürcher, Xuanxueprovided a reinterpretation of Confucianism “primarily based on the philosophy of the Book of Changes, mingled with ideas extracted from early Taoist [Daoist] thought (notably from Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu [Laozi and Zhuangzi]).” [5] It also borrowed concepts and constructions that had been newly introduced to China by Buddhism in order to fill an apparent “vacuum” in the scholastic metaphysics of Confucianism. [6] All these intellectual resources helped to establish the early standards and methodologies of character appraisal. [7]

At its center, the Shishuo features primarily Xuanxue scholars who were celebrated for their colorful and somewhat irreverent personalities, their wide-ranging philosophical and artistic accomplishments, their outspoken criticism of contemporary politics, and their love of nature and freedom. In short, their lives and exploits exemplified the Wei-Jin intellectual spirit.

A major spiritual resource for these individuals, pertinent to the focus of this article, was the notion of the “Perfected Person” (zhiren 至人) from the Daoist classic Zhuangzi莊子. This term refers to one who avails of the “right course” (zheng 正) of Heaven and Earth, rides the changes of the “six vital energies” (liuqi 六氣), and is thus able to wander the cosmos without any constraints or limitations. [8] This Perfected Person possesses special qualities and capacities, as described by Zhuangzi in his discussion of a closely connected variant notion, the Spiritual Person (shenren 神人) – a being

. . . with skin like ice or snow, and gentle and shy like a virgin girl. The Person doesn’t eat the five grains, but sucks the wind, drinks the dew, climbs up on the clouds and mist, rides a flying dragon, and wanders beyond the four seas. By concentrating his [or her] spirit, this Person can protect creatures from sickness and plague and make the harvest plentiful. [9]

. . . 肌膚若冰雪,(綽) [淖] 約若處子。不食五穀,吸風飲露。乘雲氣,御飛龍,而遊乎四海之外。其神凝,使物不疵癘而年穀熟。

Such Persons, according to the Zhuangzi, absorb natural essences, and in so doing they develop transformative powers over the world. Accompanying this idea of transformative cosmic power is a “feminine” image – expressed in descriptions of beauty, gentleness and nurture. In this egalitarian view, spiritual perfection and human efficacy were clearly available to women as well as men.

The Eastern Jin (317–420) elaboration of the Perfected Person ideal by adepts of both Xuanxue and Mahāyāna Buddhism suggests mantic ability. Drawing upon the Zhuangzi to interpret PrajñāpāramitāSutras and vice versa, the adepts of this period re-conceptualized the Perfected Person to represent “an amalgamation of secular and Buddhist thought.” [10] In their vision, especially as expressed by the eminent monk Zhi Dun 支遁 (314–366), the Perfected Person possessed a spirit, shen 神, which was at once decidedly quiet and extremely alert. Standing firmly on this immovable and creative self, the Perfected Person does not yield to outside powers but remains open to an ever-changing phenomenal world, employing a limitless repertoire of appropriate responses.

Such a Person can thus muster all kinds of intellectual and empathetic resources from the past and the present and can act sensitively and effectively in accordance with the changes of the world. In the process, the Perfected Person’s spirit brings that Person’s inner attributes to his or her appearance, bridging the gap between the Person and the outside world. As a result, “when the Person’s inner qualities are intelligent, his/her spirit appears luminous” (質明則神朗). “With a luminous spirit [the Person] foresees the future and makes ensuing judgments. Being able to understand the past and the present with good judgment (jian 鑒), the Perfected Person can thereby know the future” (神朗則逆鑒,明夫來往常在鑒內,是故至人鑒將來之希纂). [11]

Eastern Jin character appraisal appropriated Perfected-Person qualities in its evaluation standards. The Person’s capacity to “foresee the future and make ensuing judgments” (nijian 逆鑒) naturally became an indispensable component of the ideal personality portrayed in the Shishuo. In classifying the thousand-plus Shishuo episodes into thirty-six personality types, the Shishuo authors devoted the category “Technical Understanding” (Chapter Twenty) primarily to mantic practices, with similar cases sporadically spread throughout the entire work, especially in the chapter titled “Recognition and Judgment” (“Shijian” 識鑑), which focuses on character-appraisal activities. Divinatory practices in these cases not only displayed a person’s mantic talents, but also served as a means of recognizing and judging the character traits of others, and how they might respond to situational changes. Contextualized by the Shishuogenre as a form of character analysis, divinatory practices were never purely techniques (shu 術); rather, they always interacted with insightful perceptions and deep understandings of human personalities.

In a more general sense, character appraisal was a way of divining that predicted a person’s future by synthesizing all sorts of divinatory methods and theories, trespassing between the natural and supernatural orders (which were actually inseparable from the standpoint of traditional Chinese cosmology), and observing a person and/or a situation from multiple perspectives. Later Shishuo imitations invariably followed this taxonomic scheme (see Appendix), with modifications to fit the particular socio-political and cultural circumstances of each Shishuoti work.

The opening episode from the chapter “Recognition and Judgment” can serve to showcase the Shishuo’s deceptively simple anecdotal approach:

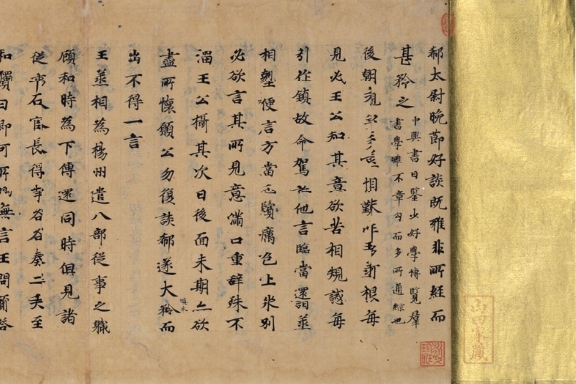

When Cao Cao [155–220] was young, he had an interview with Qiao Xuan [fl. late 2nd cent.]. Xuan told him, “The whole realm is now in disorder, and all the warriors are struggling like tigers. Aren’t you the one who will control the situation and get it in order? . . . You really are [i.e. can be] an intelligent hero [yingxiong] in an age of disorder, and a treacherous rebel in an age of order. I regret that I am old now and won’t live to see you come to wealth and honor, but I will entrust my sons and grandsons to your care.” (7/1 [Chapter 7/Episode 1]) [12]

曹公[操]少時見喬玄,玄謂曰:“天下方亂,群雄虎爭,撥而理之,非君乎?然君實是亂世之英雄,治世之奸賊。恨吾老矣,不見君富貴,當以子孫相累。”

This episode exemplifies an enduring character-appraisal practice that amounted to a form of divination: Qiao Xuan as a “diviner” predicted Cao Cao’s political future in terms of two radically different possibilities available to a person of his particular character. The episode does not detail the mantic methods that Qiao employed; his prediction may have resulted from a combined set of factors: Cao Cao’s facial structure (mianxiang面相; a type of divination known generically as “physiognomy” [fengjian風鑑, kanxiang看相, kanren看人, xiangren相人, etc.]), his remarks, his body language, and information about Cao’s background, behavior, and character gathered from other sources. In other words, the evaluative methods he employed may have ranged from the explicitly mantic to a variety of social, political and psychological variables.

There is no indication of Cao Cao’s reaction to this appraisal. But judging from Qiao’s decision to “entrust” his offspring to Cao’s care, we may surmise that both he and Qiao must have been comfortable with both possibilities – whether Cao became an “intelligent hero” or a “treacherous rebel.” According to Liu Jun’s 劉峻 (462–521) commentary on the Shishuo, when Cao heard a similar remark about his character on an earlier occasion, he “laughed out loud,” for what clearly mattered to Cao Cao was capability, not morality. [13]

The Shishuo characterization of Cao Cao is consistent with his image in conventional historical accounts. Cao lived through the collapse of the Han 漢 (206 BCE–220) dynasty, at a time when the Yellow Turban Rebellion (184–188) had torn the entire empire asunder, and contending warlords were keeping it divided. The times desperately required capable officials to help restore order. In the fifteen years of the Jian’an 建安 reign (196–220), Cao Cao, as the regent/prime minister of the declining Han and the founder of the future Wei 魏 regime (220–265), ordered a search for talented persons on four separate occasions. [14] His view was that “a time of peace and order honors moral behavior, whereas a time of anarchy and disorder values contributions and ability” (治平尚德行,有事賞功能). [15] Accordingly, he openly advocated abandoning moral standards in favor of “selecting only those who possess ability” (唯才是舉), [16] seeking to employ individuals who were “neither benevolent nor filial, but capable of ordering the state and commanding military troops” (不仁不孝,而有治國用兵之術). [17]

The relationship between divination and character appraisal is clearer in another Shishuo episode in the chapter titled “Admonitions and Warnings” (“Guizhen” 規箴):

He Yan and Deng Yang had Guan Lu construct a hexagram for prognostication, saying to him, “We don’t know if our status will reach the Three Ducal Offices or not.”

When the hexagram was completed, Lu quoted the ancient interpretations, warning them gravely. Deng Yang said, “This is the usual talk of an old scholar.”

But He Yan said, “‘To know the springs of action – how divine!’ This is what the ancients considered difficult. Distant in friendship, yet still sincere in what one says. This is what men of today consider difficult. Today, in one stroke, you have satisfied the requirements of both difficulties. This is what is meant by the statement, ‘Illustrious virtue is a far-reaching fragrance.’ Isn’t there a line in the Book of Songs which goes: ‘In my utmost heart I’ve hid it, / What day could I forget it!’” (10/6) [18]

何晏、鄧颺令管輅作卦,云:“不知位至三公不?”卦成,輅稱引古義,深以戒之。颺曰:“此老生之常談。”晏曰:“知幾其神乎,古人以為難;交疏吐誠,今人以為難。今君一面,盡二難之道,可謂‘明德惟馨’。詩不云乎,‘中心藏之,何日忘之!’”

Here, the Shishuo authors have omitted the details of Guan Lu’s divinatory use of the Book of Changes, focusing instead on a character appraisal process that exposes the personalities of all three participants through their mutual evaluations. Clearly aware of the current political situation, Guan Lu draws upon ancient interpretations of the Changes to caution He Yan and Deng Yang against imprudent ambition. In their responses, Deng and He each place a judgment on Guan’s character and in turn reveal their own. Deng appears arrogant and frivolous. He quickly dismisses Guan’s sophisticated interpretation as “the usual talk of an old scholar,” showing his disappointment because he has posed a question revealing the political aspirations of the two men. He Yan, unlike Deng, appears modest and grateful. He posits the question because he has sensed threats to his otherwise promising career. He recognizes Guan Lu’s divine talent and appreciates Guan’s sincerity, showing himself to be, like Guan, a sensitive adept of character appraisal. [19]

The following Shishuo episode from “Technical Understanding,” revolving around Guo Pu’s 郭璞 (276–324) exalted reputation as a practitioner of geomancy (zhan zhongzhai 占塚宅, kanyu 堪輿, fengshui 風水, etc.), is similarly revealing with a rather humorous touch:

Emperor Ming of Jin [Sima Shao, r. 323–325] understood how to make geomantic divinations concerning tombs and houses. On hearing that Guo Pu was undertaking someone’s burial, the emperor went in mufti to watch and took the opportunity to ask the head of the household, “Why are you burying him at the dragon’s horn? This way you’ll bring about the termination of your entire clan.”

The head of the household replied, “Guo Pu told us, ‘This is a burial at the dragon’s ear, and in less than three years there will come a Son of Heaven.”

The Emperor asked, “Does this mean the family will produce a Son of Heaven?”

He replied, “It’s not that they’ll produce a Son of Heaven. It’s just that there could come a Son of Heaven asking questions, that’s all.” (20/6) [20]

晉明帝解占塚宅,聞郭璞為人葬,帝微服往看,因問主人:“何以葬龍角?此法當滅族!”主人曰:“郭云:‘此葬龍耳,不出三年,當致天子。’”帝問:“為是出天子邪?”答曰:“非出天子,能致天子問耳。”

This episode considers the two personalities through the lens of an implicit rivalry or tension between them. Guo Pu, a famous diviner well versed in both geomancy and character appraisal, is aware that Emperor Ming, a mediocre diviner, has kept a close scrutiny of Guo’s geomantic activities out of personal jealousy. He thus instructs the head of the household about how to address the emperor’s possible query, as well as how to correct the emperor’s mistake without offending his imperial authority. Although Guo does not actually appear in the scene, his witty and humorous personality steers the conversation.

The divinatory practices in the Shishuo, which reveal the social, political, and intellectual circumstances of the times in which they were employed, consisted not only of physiognomy, use of the Book of Changes, and geomancy, but also time-honored techniques such as dream interpretation and the analysis of sounds. At least some of these practices, as applied during the Later Han and Wei periods, were documented and theorized in the Wei scholar Liu Shao’s 劉卲 (fl. 168–172) Treatise on Personalities (Renwu zhi 人物志).

From the beginning of recorded history in China (the Shang 商dynasty, c. 1600–c. 1046 BCE), dream interpretation (jiemeng解夢, mengzhan 夢占, etc.) was a prominent feature of Chinese mantic practice. Not surprisingly, then, the Shishuo took dreams very seriously. Here is an example:

When Wei Jie [286–312] was a young lad with his hair in tufts, he asked Yue Guang [252–304] about dreams.

Yue said, “They are thoughts (xiang 想).”

Wei continued, “But dreams occur when body and spirit aren’t in contact. How can they be thoughts?”

Yue replied, “They are the result of causes (yin 因). No one has ever dreamed of entering a rat hole riding in a carriage, or of eating an iron pestle after pulverizing it, because in both cases there have never been any such thoughts or causes.”

Wei pondered over what was meant by “causes” for days without coming to any understanding, and eventually he became ill. Yue, hearing of this, made a point of ordering his carriage and going to visit him, whereupon he proceeded to make a detailed explanation of “causes” for Wei’s benefit. Wei immediately began to recover a little.

Sighing, Yue remarked, “In this lad’s breast, there will never be any incurable sickness.” (4/14) [21]

衛玠總角時問樂令[廣]“夢”,樂云“是想”。衛曰:“形神所不接而夢,豈是想邪?”樂云:“因也.未嘗夢乘車入鼠穴,擣齏噉鐵杵,皆無想無因故也。”衛思“因”,經日不得,遂成病.樂聞,故命駕為剖析之。衛既小差,樂歎曰:“此兒胸中當必無膏肓之疾!”

Here, Yue Guang’s response to Wei Jie draws upon the hallowed text known as the Zhou Rituals (Zhouli 周禮), which lists six types of dreams, all related to one’s conscious thoughts. [22] The prodigy Wei Jie, however, questions this explanation, arguing that dreams evolve inside of one’s brain, which is part of one’s body (xing 形), beyond the control of one’s spirit (shen 神). Yue Guang thereupon adduces another explanation, namely yin, or cause. But the real point of the episode is, of course, that a sophisticated discussion of dreams gives Yue the opportunity to evaluate Wei Jie’s character, revealing the boy’s precociousness and stubborn pursuit of answers to his well-informed questions.

Another episode addresses some specific characteristics of Chinese dream interpretation:

Someone once asked Yin Hao [306–356], “Why is it that

[When one is] about to attain office,

One dreams of coffins;

[When one is] about to gain wealth,

One dreams of filth?”

Yin replied,

“Office (*kuân 官) is basically ‘stinking decay,’

So someone about to attain it,

Dreams of coffins (*kuân棺) and corpses.

Wealth is basically ‘feces and clay,’

So someone about to gain it

Dreams of foul disarray.” (4/49) [23]

人有問殷中軍:「何以將得位而夢棺器,將得財而夢矢穢?」殷曰:「官本是臭腐,所以將得而夢棺屍;財本是糞土,所以將得而夢穢汙。」

This explanation weaves together a web of interdependent, correlated, and interrelated causes. It instigates a variety of senses – homophones are caught by the ears and their similar written forms are caught by the eyes, and the “stinking decay” and “feces and clay” are smelt by the nose and seen by the eyes. The interpretation also touches on different dimensions of experience and intellectual life, including linguistic, psychological, ethical, and philosophical. Yin Hao’s answer to the query about dream symbolism reflects, in part, the oppositional logic that was central to certain kinds of dream interpretation, [24] but more fundamentally, his explanation reveals Yin Hao’s position as a Xuanxue scholar, who engages both Zhuangzi and Confucius’ disdain for rank and wealth. [25]

III. Shishuo Imitations in China

Imitation of the Shishuo began in the Tang 唐 (618–907) dynasty. Various bibliographic records reveal three Shishuo ti works from this period: Continuation of the Shishuo xinshu (Xu Shishuo xinshu 續世說新書) by Wang Fangqing 王方慶 (d. 702), Feng’s Memoirs (Fengshi wenjian ji 封氏聞見記) by Feng Yan 封演 (fl. 742–800), and New Account of the Great Tang (Da-Tang xinyu 大唐新語) by Liu Su 劉肅 (fl. 806–820). [26] Two points are especially significant. First, although these works might have added to, or deleted some categories from, the ur-text, their authors always retained the chapters on “Recognition and Judgment” and “Technical Understanding,” showing their appreciation of “character appraisal” as the focal theme of the genre.

Secondly, unlike the original text, Tang Shishuo tiworks introduced strong Confucian ethical overtones into the genre. As Liu Su put the matter in concluding his New Account of the Great Tang, his goal was “to hail the ruler and to humble the subject, and to expel heterodoxy and to return to rectitude” (尊君卑臣,去邪歸正). [27] The movement from the Shishuo’s relatively neutral classification of human character types to a differentiation between “rectitude” (zheng 正) and “heterodoxy” (xie 邪) marked a dramatic shift from aesthetic to ethical concerns. As a result, the mantic practices discussed in the Tang Shishuo ti works sometimes reveal a self-conscious effort to support political leaders. A good example, as we shall see below (Section V), was an effort to establish the authority of Empress Wu Zetian 武則天 (r. 684–704), whose rise to power was marked by considerable controversy.

Only two Shishuo ti works from the Song 宋 (960–1279) exist today: Kong Pingzhong’s 孔平仲 (fl. 1044–1111, js 1065) Continuation of the Shishuo (Xu Shishuo 續世說) and Wang Dang’s 王讜 (fl. 1086–1110) Tang Forest of Accounts (Tang yulin 唐語林). As is well known, the Song was a period of enormous philosophical energy and diversity – one that witnessed, among many other things, a surge of scholarly interest in the Book of Changes and other mantic works. [28] It was also a time when fierce debates raged about the place and purpose of literature in the dynasty’s political, social, intellectual and cultural life.

As members of an intellectual circle headed by the famous scholar-official Su Shi 蘇軾 (1036–1101), Kong, Wang and Su had similar ideological, historical, and literary interests and concerns. [29] Perhaps the most important of these was a great esteem for the power and potential of literature. Some prominent thinkers of the early Song period, like Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤 (1017–1073) and Cheng Yi 程頤 (1033–1107), felt that literature might work at cross purposes with the pursuit of “truth” as they understood it. They argued that writing (wen 文) was, in a relatively narrow sense, simply “a vehicle for the Way” (wen yi zai dao 文以載道), not a means of actually accessing the Way itself. But individuals like Kong, Wang and Su believed that writing, as a creative, individual, subjective endeavor, offered the only true means by which to “become one with the Way.” [30] In the eyes of Kong and Wang, the Shishuo genre, embracing a kaleidoscopic range of intellectual interests and bringing together diverse literary modes, provided a path to constructing and understanding the authentic “self.”

The category “Technical Understanding” in Kong’s Continuation of the Shishuoreflects not only the author’s literary preoccupations, but also the more general explosion of interest in metaphysics and mantic methods during the Song period. The number of entries in this category increased from eleven in the original Shishuoto thirty-eight in Kong’s imitation, and the methods now included astrology and astronomy (zhan tianwen 占天文; #1, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 26, 38), the analysis of animal sounds (waming蛙鳴, niaoming 鳥鳴, etc.; #2, 25), Changes-related divination using oracle bones and/or milfoil stalks (bushi 卜筮; #3, 5, 17, 35), physiognomy (xiangshu 相術; #4, 6, 7, 14, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37), yin-yang and five agents mantic methods (yinyang wuxing 陰陽五行; #8, 21), numerology (busuan 布算; #15), musical analysis (xuangong 旋宮; #18), fate extrapolation based on cosmic variables (tuisuan 推算; #19), medicine and divination (yishu 毉術; #27), and talismanic writing (fulu符錄; #33). [31] These amplified records of mantic practices reflect not only the greatly enlarged intellectual territory of the Song dynasty, but also, and especially, the increasing interaction between elite and popular culture that marked this dynamic period. [32]

As is apparent from the above breakdown, Kong devoted a great deal of attention to physiognomy, which is hardly surprising, given the emphasis on personal characteristics in the Shishuogenre. Here is one example. Jia Ziru 賈子儒 (fl. mid sixth cent.) divined whether the Eastern Wei generalissimo Gao Cheng 高澄 (d. 549, posthumously titled Emperor Wenxiang 文襄 of the Northern Qi) could ascend the throne, saying: “[To tell one’s fate] by looking at one’s seven-foot tall body is not as accurate as observing one’s one-foot face, which, in turn, is not as accurate as observing one’s one-inch eyes. The generalissimo has a thin face and a quick gleam of the eyes – not the appearance of a ruler!” (人有七尺軀,不如一尺面;一尺面,不如一寸眼 大將軍臉薄盼速,非帝王相也) (#14). [33] As it turned out, Gao, who was considered able but arrogant and licentious, was assassinated by his servant Lan Jing 蘭京 before he could seize the throne. [34]

Like Kong Pingzhong, Wang Dang adopted the original Shishuomodel, but expanded it into fifty-two taxonomic categories. Although the extant version of the Tang Forest of Accounts consists of only the first eighteen chapters, we can see in Chapter Seven, “Recognition and Judgment,” a number of physiognomic cases (#4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 18). Moreover, in his accounts of Tang literati life, which contributed to the flourishing of Tang poetry, Wang recorded numerous instances of divination based on poetic creativity (#1, 15, 16), as well as several involving music-related mantic methods (#5, 7, 14). [35] Although both developments had been foreshadowed in the original Shishuo chapters on “Literature and Scholarship” (“Wenxue” 文學) and “Technical Understanding,” the Tang Forest of Accounts made divination a more explicit theme.

The trend of tying mantic practice to one’s literary/artistic accomplishments was linked directly to the flourishing of the Tang civil examination system, which paved the way for talented men to enter officialdom. Thus, we encounter stories in the TangForest of Accounts such as the following – this one recorded in the chapter on “Recognition and Judgment”: Li Jue 李玨 lost his father in his early years and became known for his filial devotion to his widowed mother. He was subsequently recommended by the local authorities to take the mingjing 明經 examination, which tested one’s elucidation of the Confucian classics. When Li Jue went to see the Huazhou Governor Li Jiang 李絳, the governor looked at him and made the following comments: “With a forehead as illustrious as the sun and as pure as a pearl, you are not an ordinary person. You will be able to obtain the jinshi 進士 degree. As for the mingjing exam, it is too ordinary a foundation for your glorious future” (日角珠庭,非常人也,當掇進士科。明經碌碌,非子發跡之地). Later Li Jue passed the jinshi examination (which required poetic creativity along with knowledge of the Confucian classics) and had a successful career, serving not only as governor-general of a few strategic states, but also as prime minister (#18) [36].

Most Chinese Shishuoimitations emerged in the late Ming and early Qing periods, from the 1550s to the 1680s. The authors of these works, primarily from the lower Yangzi delta, followed Song Shishuo authors, taking literature as the means to reach the Way. This approach became intensified in their sharply negative reaction to the ideas of Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) – known as the School of Principle (Lixue 理學) – which had become state orthodoxy in the Yuan 元dynasty (1279–1368) and continued to enjoy state support during the Ming 明 (1368–1644) and Qing 清 (1644–1912) dynasties. In their effort to rid themselves of the Lixue confinement, they acquired a sense of cultural and intellectual distinctiveness not unlike that of their Wei-Jin predecessors. Thus, they naturally sought to transmit their well-wrought discourse of literati spirit through the Shishuo genre, including using mantic practices for character appraisal. [37]

The Ming scholar He Liangjun 何良俊 (1506–1573) inaugurated a frenzy of Shishuo imitations with his book titled He’s Forest of Accounts (Heshi yulin 何氏語林). In it, he theorized the Shishuo taxonomy by attaching a preface to each of the thirty-six original categories, in addition to two of his own invention. The preface to his chapter on “Recognition and Judgment” reads:

Generally speaking, human feelings are deep, difficult to fathom, and worldly situations are mutually dependent, hard to judge. Is it not even more difficult to predict one’s future at a young age, and to know the features of something before it takes shape? The Book of Documents says: “Knowing people is wisdom – even the Sage Kings found it difficult”; and the Book of Changessays: “To know the springs of action – how divine!” These are not empty words! […] The Sage has a heart/mind like the luminous mirror; therefore the Sage can comprehend a person in [his/her] entirety. […] The Book of Changes also states: “[The Changes] are quiescent and do not move. But if they are stimulated, they penetrate all situations under Heaven.” [38] Buddhists, too, maintain: “Eternal quiescence leads to eternal illumination.” Both follow the Dao. Later scholars are far away from the [models of the] ancient Sages and worthies, whose evaluations and characterizations of people and their extrapolation and discernment of things and events were often wondrously accurate. […] Why? It is because scholars after the Later Han favored Daoism and Buddhism, and the Song scholars liked to debate about principles and human nature. Alas, how can one slander the achievements of pure and abstruse learning! [39]

夫人情深阻而莫測,事勢倚伏而難定。況乎人方幼而審其終,事未形而能知其著,可不謂尤難哉!《書》曰:“知人則哲。維帝其難之”《易》曰:“知幾其神乎!”不虛耳!. . . 蓋聖人者,心如明鏡,遇物便了. . . .《易》稱:“寂然不動,感而遂通。”釋氏所謂“常寂常照”,皆此道也。後世去古聖賢甚遠,然觀其品校人物,推測事幾,多奇中. . . 何耶?蓋東漢以後尚老釋,宋世好談理性,嗚呼,清虛澄汰之功,又焉可誣也!”

Here, He Liangjun affirms that character appraisal and the extrapolation of situational changes have both been central intellectual concerns since the beginnings of philosophy in China, and that their importance had not only been discussed in the major Chinese classics, but had also been validated by certain ideas derived from Daoism and Buddhism.

In the chapter on “Technical Understanding,” for example, He evinces a particular interest in music-related methods (eighteen out of 49 accounts), followed by physiognomy and medicine (seven accounts each). He also provides information on Buddhist esoteric magic (four accounts), as well as more regular divinatory techniques such as astronomy/astrology, numerology, and so forth. A remarkable account concerning music tells about the wretched life of the Tang crown prince Li Xian李賢 (654–684, posthumously titled Zhanghuai 章懷). The story goes like this: Li Xian composed the “Melody of Precious Celebration” (“Baoqing qu” 寶慶曲) during the reign of his father, Emperor Gaozong of the Tang (r. 649–683), and presented it at the Daoist Abbey of Grand Purity (Taiqing guan 太清觀). Upon hearing this melody, Li Sizhen 李嗣真, a courtier, made the following comments to Abbot Liu Gai Fuyan 劉概輔儼:

[Among the Five Tones of the pentatonic scale (gong-shang-jue-zhi-yu宮, 商, 角, 徵, 羽, equivalent to do-re-mi-sol-la)], the gong tone in this melody is not in harmony with the shang tone, hence there is opposition between ruler and subject; the jue tone is in conflict with the zhi tone, hence father and son do not trust each other. Moreover, the music abounds in the sound of death and is full of sadness. If this bad omen does not afflict the state, then it will bring misfortune to the crown prince” (宮不召商,君臣乖也; 角與徵戾,父子疑也。死聲多且哀。若國家無事,太子任其咎).

Before long, the crown prince was demoted to the rank of commoner and exiled by his mother Wu Zetian (#32). [40] He Liangjun very likely adopted this story from the New Account of the Great Tang by Liu Su, which, however, did not indicate Li Xian as the composer. [41] By adding Li Xian’s name, possibly drawn from some other sources, He Liangjun reinforced the mantic dimensions of this story, showing that the poor prince was destined for his tragic ending.

Jiao Hong 焦竑 (1541–1620, js 1589) was among a number of followers of He Liangjun to compile a Shishuo ti work. His chapter on “Technical Understanding” in the Jiao's Taxonomic Forest (Jiaoshi leilin 焦氏類林) is comprised of forty-eight entries, about the same length as in He Liangjun’s book. Jiao, however, spreads his accounts of mantic methods more evenly in the fashion of Kong Pingzhong’s Continuation of the Shishuo. For instance:

Emperor [Shizong of the Jin, 金世宗r. 1161–1189] asked his prime-minister, Heshilie Liangbi 紇石烈良弼 [1119–1178], why it was that “every morning and every evening the sun turns red.” Liangbi responded: “That the sun turns red in the morning should correspond to what happens in the east, so Goryeo [Korea] should take the blame. That the sun turns red in the evening should correspond to what happens in the west, so the Tanguts should take the blame. I wish Your Majesty could cultivate your virtue in response to Heaven. That way, any disaster would disappear by itself.” Soon afterward, Ren Dejing rebelled in the Tangut Empire and Zhao Weichong rebelled in Goryeo, affirming Liangbi’s prediction (#48). [42]

帝[金世宗]問紇石烈良弼:“每旦暮日色皆赤,何也?” 良弼曰:“旦而赤色,應在東,高麗當之。暮而赤色,應在西,夏國當之。願陛下修德以應天,則災變自弭矣!”既而夏國有任德敬之亂,高麗有趙位寵之難,其言皆驗。

Another important late Ming Shishuo ti work was Li Shaowen’s 李紹文 (fl. 1600–1623) Imperial Ming Shishuo xinyu (Huang Ming Shishuo xinyu 皇明世說新語). Its chapter on “Technical Understanding” focuses on what may be called dynastic destiny – that is, the perceived link between early predictions by diviners and the actual fate of the Ming state (1368–1644). A prominent mantic method displayed in Li’s work was the technique known as “fathoming” or “dissecting” characters (cezi 測字 or chaizi 拆字). Here is an example based on the early career of Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋. Zhu eventually became the founder of the Ming dynasty (r. 1368–1398), but at the time of this story he was merely a rebel opposing the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368).

When the future Emperor Taizu [Zhu Yuanzhang] first crossed the Yangzi River, he consulted a diviner whom he encountered on his way, asking: “Now that the whole world is in turmoil, who will become the ruler of all under Heaven?” Zhu told the diviner that he wanted to write a word for him to analyze, and pulled out his sword to draw a line (which stood for the Chinese character “one” [yi 一]) on the ground. The diviner immediately kowtowed to Zhu, saying: “A line on top of dirt (tu土), it can only mean that you will be the King (wang 王)!” [43]

太祖初渡江,遇一術士,問曰:“天下擾擾紛紛,屬之誰?”與士曰:“願書字占之。”上即拔劍畫“一”字於地。士俯伏拜曰:“土上一畫,臣獨知為王也!

The last Shishuo ti work to be produced in China was Yi Zongkui’s 易宗夔 (b. 1875) New Shishuo (Xin Shishuo 新世說), compiled during the tumultuous New Culture Movement (a.k.a. the May Fourth Movement; c. 1915–1925). This period was marked by an assault by iconoclastic Chinese intellectuals on virtually every aspect of traditional Chinese culture, from Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism to the family system, from classical literature to divinatory practices. At the same time, these intellectuals embraced new Western ideas and values, including such essentially alien concepts as constitutionally protected freedom, equality, individualism and democracy. Standing in this temporal and spatial border zone, with a clear view of both the past and the present, and of both China and the West, Yi grappled with how to describe and understand a society that had undergone unprecedented changes in the span of little more than two decades. [44] These developments included the fall of the Qing dynasty and the destruction of the entire imperial system as a result of the Republican Revolution of 1911–12.

Not since Kong Pingzhong’s Song dynasty compilation, Continuation of the Shishuo, do we find such a preoccupation with divination, with such a wide range of mantic practices discussed. The chapter on “Technical Understanding” in Yi’s New Shishuo is comprised of thirty-two entries [45] The methods include: Changes-related divination using oracle bones and/or milfoil stalks (bushi卜筮; #1, 3, 10, 11, 18, 25), deciphering covered objects (shefu 射覆; #2), fathoming or dissecting characters (cezi 測字 or chaizi 拆字; #4, 13), combining medicine and divination (yibu 醫卜/毉卜; #5), employing geomancy or siting (fengshui 風水or kanyu 堪輿; #5, 6), detecting wind patterns (fengjiao 風角; #5, 7, 22), calculating “six waters” (divination) and “wondrous gate evasive techniques” (liuren 六壬 and qimendunjia 奇門遁甲; #7, 14, 15, 21, 25), interpreting the “eight military diagrams” (bazhen tu 八陣圖; #8), practicing physiognomy (xiangshu 相術; 9, 16, 27, 28), analyzing music (xuangong 旋宮; #12), reading the eight [natal] characters (bazi八字) (#17), correlating the five agents (wuxing 五行); #17), employing secret spells from the West (Xiyu mimizhou 西域秘密呪; #23), practicing numerology (shuxue 數學; #24, 31), engaging in spirit-writing (fuluan扶乩, fuji 扶箕 or fuluan 扶鸞; #26, 32), consulting the “heavenly eye” (tianyan tong 天眼通; #29), and hypnotizing people (cuimian shu 催眠術; #30). [46] Several factors may have contributed to there being such an extensive discussion of these mantic methods: (1) the prevalence of these practices in the Qing, especially at a time of uncertainty, when the dynasty was in decline; (2) the introduction of new divinatory techniques from the West; and (3) a heightened awareness of divination because it was the object of so much criticism during the New Culture era.

In any case, three features of Yi’s discussions of divination are worthy of note. The first is the author’s preoccupation with dynastic destiny. One story concerns the Manchu Prince Dorgon 多爾袞 (1612–1650), who inquired about the future of his military campaign against the Ming dynasty. The diviner predicted good fortune, adding, however, that the regime “would be gained by a Prince Regent and lost by a Prince Regent” (得之者攝政王,失之者亦攝政王也). The diviner also indicated that the throne would be “acquired by a widow and an orphan and lost by a widow and an orphan” (寡婦孤兒得之,寡婦孤兒失之). Although Dorgon had planned to become Emperor of China after conquering the Ming, he eventually decided to surrender the crown to Fulin 福臨, the six-year old son of his late brother Hong Taiji 皇太極 (1592–1643). Fulin subsequently ruled as the Shunzhi 順治emperor (r. 1644–1661) with Dorgon as a co-regent, thus fulfilling the prophesy. And when the Qing dynasty fell, it was in the hands of the Prince Regent Zaifeng 載灃 (1883–1951), who ruled together with Empress Longyu 隆裕 (1868–1913), widow of the Guangxu 光緒 emperor (r. 1875–1908), and their adopted son Puyi 溥儀 (1906–1967; #3). [47]

The Shunzhi emperor, for his part, consulted with a Tibetan lama about the destiny of the Qing dynasty. The lama’s cryptic answer was, “As long as my body is intact, my dynasty will not be exterminated” (我身不缺,我國不滅). A semantic reading might have put the emperor at ease, for all he and his successors had to do, presumably, was not to endanger their persons. But a word analysis (chaizi 拆字) of the prediction suggests a more ominous outcome. When the three-year old Puyi 溥儀 ascended the Qing throne, his name, including the character yi 儀, became taboo, and had to be modified by the elimination of the last stroke of the radical wo 我 (I, me, my). With the initiation of this policy, his “body” was mutilated and the Qing dynasty fell (#4). [48]

A second important feature of Yi’s discussions of divination in the New Shishuo is that they include a great many prominent Qing intellectuals – not just professional diviners or clerics. Yi’s work is full of accounts of high-level scholars, including such noted individuals as Lu Qi 陸圻 (b. 1614), Sun Zhi 孫治 (fl. 1661), Jiang Yong 江永 (1681–1762) Lü Liuliang 呂留良 (1629–1683), Shi Kuijiang 史夔江 (fl. 1681), Ji Huang 嵇璜 (1711–1794), Ma Yan 馬嚴 (js. 1796), Zeng Guofan曾國藩 (1811–1872), and even the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor (r. 1736–1795). [49] Here is an example of Yi’s approach, which cites a physiognomic manual reportedly written by Zeng, a famous late Qing scholar-general:

To know if one is evil or righteous, look at one’s eyes and nose, and to determine true or false, look at one’s lips. To predict one’s success in an official career, look at one’s aura, and to determine wealth, look at one’s spirit. To decide if one possesses independent ideas, look at one’s fingernails, and if one can stir things up, look at the veins in one’s heels. If we want to know if one is well organized, that’s all in one’s spoken words.

Also, if one looks dignified and solemn, such is the sign of a noble person; the same is true if one looks humble, modest, and restrained. If one is good in management, this is the sign of a wealthy person; the same is true if one possesses a merciful heart/mind and is willing to help others. (#28) [50]

邪正看眼鼻,真假看嘴唇,功名看氣概,富貴看精神,主意看指爪,風波看腳筋,若要看條理,全在語言中。”又云,端莊厚重是貴相,謙卑含容是貴相,事有歸着是富相,心存濟物是富相。

Significantly, Zeng’s physiognomic techniques are extremely popular in today’s China, where divinatory methods of all sorts have experienced a comeback after decades of government suppression. [51]

One divinatory practice that proved especially appealing to scholars in the Qing dynasty was “spirit-writing,” a Tang-Song innovation. Early spirit possession in China did not generally involve literacy, but by the Song period it had come to be associated closely with the scholarly elite, merging over time with the traditions of “morality books” (shanshu 善書) and “precious scrolls” (baojuan 寶卷) in Chinese popular religion. Its particular importance to Qing intellectuals was its presumed value as a means of providing guidance to examination hopefuls. For instance, in 1843, during the Daoguang 道光 reign, a group of Huzhou 湖州 candidates used spirit-writing to divine the test topic for the upcoming provincial examination. The spirit descending on the altar wrote down two lines: “Between white clouds and red leaves” (在白雲紅葉之間), and “I do not read the Spring and Autumn Annuals” (吾不讀《春秋》).

No one was able to figure out the meaning of the two lines until the release of the topic, which required candidates to write essays on a pair of verses taken from the Analects of Confucius (Lunyu 論語). These two verses were located between one that ended with fuyun 浮雲 (floating clouds) and one that began with Shegong 葉公 (Lord She). Because the character she 葉 was also pronounced ye, meaning “leaves,” it should have been circled in red ink to draw the reader’s attention to it. Hence, the topic was indeed between “white clouds” and “red leaves”! In addition, the two verses assigned in the topic mentioned four of the five Confucian classics, leaving out only the Spring and Autumn Annuals (Chunqiu春秋), which the spirit had indicated he “would not read” (#26). [52] Whether this was a true story or one made up as a joke after the examination, the episode exemplifies the kind of Chinese cultural practices involving divination that prized erudition and wit.

IV. Shishuo Imitations in Japan

Although Japanese versions of the Shishuo ti tended to reflect time-honored Chinese themes and categories, they also expressed distinctly Japanese cultural traits, psychological attitudes, and philosophical positions as they evolved over time. Written in a form of classical Chinese known as “Han writing” 漢文 (pronounced Kanbun in Japan, Hanmunin Korea, and Hán văn in Vietnam), they were more than simply the extended products of Chinese culture. Rather, they were the products of a complex, sophisticated and continuous process of cultural interaction, exchange, domestication and transformation that had been taking place in East Asia for many centuries. [53] During the Tokugawa 徳川 (1603–1868) period, when all extant Japanese versions of Shishuo ti were compiled, the process of transmission and transformation had yielded a number of different perspectives on China, from the Sinophilia of scholars such as Kumazawa Banzan熊沢蕃山 (1619–1691) and Kaibara Ekken貝原益軒 (1630–1714) to the nativist assertion of Japan’s cultural equivalence or superiority to China expressed by writers such as Yamaga Sokō山鹿素行 (1622–1685) and Kamo Mabuchi賀茂真淵 (1697–1769). [54]

Among the eight Japanese Shishuo ti works I have located, four devote a chapter to mantic practices (see Appendix). The Tales of the World in This Dynasty (Honchō Sesetsu 本朝世說), compiled by Hayashi Yoshio林怤士 (preface dated 1704), is the earliest Japanese Shishuo imitation that I have found so far. The author’s life awaits more research. Significantly, it seems that he compiled this work in order to demonstrate, among other things, that Japan’s cultural achievements were no less impressive than those of China. In his words: “The flourishing of our sacred morality, the completeness of our ritual system, the outstanding qualities of our people, and the intelligence of our Way of governing – what is there in any of this that would cause us to be shamed by China?” (神德之盛,禮典之備,人物之傑,政道之明,何以恥中華乎哉?) [55].

Hayashi Yoshio collected 127 episodes, dating from the Japan's antiquity to the Hōgen保元 reign (1155–58) in the Heian 平安 period (794–1185). Although he divided them into only ten categories, he made sure to include one titled “Occult Techniques” (“Fangshu” 方術), a variant of the original Shishuotitle of “Technical Understanding” (“Shujie” 術解) – thus underscoring his appreciation of the importance of divination in Japanese culture. This chapter consists of eleven episodes, presenting a mixture of supernatural legends and divinatory practices. Among the supernatural stories included is the following one from the famous Records of Tango Province (Tango-no-Kuni Fudoki 丹後國風土記). It details a love story involving Mizunoe no ura no Shimako 水江浦島子, a refined young man from Tango, and a beautiful fairy girl who, after transforming herself into a turtle, meets Shimako at sea, taking him to visit her fairy island (#1). This same group of records also includes stories concerning Daoist and Buddhist immortality (#3, 4, 6). The divinatory stories include various mantic activities, such as oracle bone divination (#2), astrology (#5, 10, 11), word analysis (#8, 9), and dream interpretation (#9).

One word-analysis story recounts an episode during the reign of Emperor Ichijō 一條 (r. 980–1011) in the Heian 平安 (794–1185) period in which a dog delivers its puppies inside the empress’s inner chamber just as the empress is about to give birth to her own child. Her father, Regent/Chancellor Fujiwara no Michinaga 藤原道長 (966–1027), consults Ōe no Masahira 大江匡衡 (952-1012) about this incident. Masahira tells his lordship not to worry:

The [Kanbun] character ‘dog’ (犬) has a dot by its side. Move this dot from the side to the top and you have the character for ‘Heaven’ (天), and move the dot below it and you have the character for ‘great’ (太). [Combined with the character for new-born ‘son’ (子)], you have the ‘Son of Heaven’ (天子, meaning “emperor”) and the ‘Great Son’ (太子, meaning “crown prince”). Extremely auspicious! Treasure this omen!” (“犬”字旁點,加之于上,則“天”字也;加之于下,則“太”字也。天子也,太子也,大吉珍重!).

The baby boy born to the empress subsequently became the crown prince and assumed the throne (#8) [56].

Four decades after Hayashi Yoshio produced his Tales of the World in This Dynasty, Hattori Nankaku 服部南郭 (1683–1759) published Account of the Great Eastern World (Daitō Seigo 大東世語), an expansive Shishuo imitation comprising over eight hundred accounts divided into thirty-one Shishuocategories and featuring a painted scroll of Heian 平安 (794–1185) and Kamakura 鐮倉 (1185–1333) personalities. As a prominent disciple of Ogyū Sorai 荻生徂徠 (1666–1728), a passionate admirer of China (although a critic of Mencius 孟子), and the founder of an unorthodox Japanese Confucian school of learning known as Soraigaku 徂徠學, Hattori Nankaku steadfastly championed Sorai’s well-known hypothesis concerning the immutability of human dispositions. [57] Precisely because each person maintains his/her natural status, Ogyū Sorai argued, the free development of individuality and the diversity of human personalities make the world work. [58]

Clearly Hattori’s compilation of a Shishuo imitation that elaborates the Daoist idea of each person “being one’s self” was designed as a means by which to advocate his mentor’s ideas about human nature. Seen in this light, it made perfect sense for Hattori to locate Heian and Kamakura personalities within a Shishuo frame, since the former provided the most illustrious examples of Japanese personalities in history, and the latter helped to highlight the diverse qualities of these “natural” human beings. [59] Consistent with the Shishuo, mantic practices served to characterize Daitō personalities.

Among the seven “Technical Understanding” episodes in AnAccount of the Great Eastern World, four are on physiognomy, two on astrology, and one on medicine. [60] From these cases we can see how Hattori reconciled a the Chinese cultural model with the distinctive “Japanese” features of Daitō life. In two of these stories, the objects of physiognomic attention are not people, but hunting falcons, revealing the warrior traditions of Heian life that were far from the experience of most Chinese elites. [61] In another episode, we learn that after the death of Emperor Kanna’s 寬和 (a.k.a Kazan Tennō 花山天皇, r. 984–986) favorite concubine, the grief-ridden ruler decides to abandon the throne and leave the palace secretly one night. As he passes by the house of Abe no Seimei 安[倍]晴明 (921–1005), Seimei happens to look up at the sky and sees an astrological sign indicating an “escape from the position of the Son of Heaven” (天子避位) (#4). [62] Under normal circumstances, it would be unthinkable for a Chinese sovereign to abdicate, but in Heian Japan, as we learn from reading An Account of the Great Eastern World, the Heian emperors lost their power to the Fujiwara regency (ca. 858–ca. 1158) and were relegated to mainly ceremonial and cultural activities. [63]

Discussions of other Japanese mantic methods in AnAccount of the Great Eastern World shed further light on Japan’s cultural distinctiveness. One story tells us that the Provisional Captain of the Right Division of Bureau of Horses, Fujiwara no Munetada藤[原]致忠 (fl. 947–957), [64] once had a candid discussion concerning astrology with a friend in the man’s room. An arrow suddenly enters the premises and hits a wooden pillar. Alarmed, Munetada says: “I have gone too far! I should not have talked about Heaven in a filthy place and so caused the Star of Fire (Yinghuo 熒惑, a.k.a. Huoxing or Kasei 火星, the planet Mars) to shoot at me! Luckily, this year I have the Star of Wood (Muxing or Mokusei 木星, the planet Jupiter) assisting me, so the arrow hit the wood instead of me.” [65] Once again, the warrior tradition of the samurai class seems to provide the dominant framework for interpreting this event.

Another case concerns Fujiwara no Nobunaga 藤原信長 (1022–1094). Nobunaga divines his future by looking into a well, discovering that the reflection of his face bears the omen of a prime minister. He then looks into a mirror in his room but does not see the same sign. After several attempts to obtain the same result, he sighs: “The mirror is near and the well far away. My ascending to the position of prime minister should naturally be in the far future” (鏡近井遠,吾拜相自當遠爾). This prediction, which later proved to be true (he became Dajō-daijin 太政大臣 or Chancellor of the Realm at the age of 58), links physiognomy to locations in ways that are uncommon in Chinese works of the Shishuogenre. [66]

Inspired by An Account of the Great Eastern World, Tsunoda Ken 角田簡 (a.k.a. Tsunoda Kyūka 角田九華, 1784–1855) compiled Accounts of Recent Times (Kinsei sōgo 近世叢語) (1828), and then Continued Accounts of Recent Times (Shoku Kinsei sōgo 續近世叢語) (1845). Both works reflect late Momoyama 桃山 and Edo 江戶intellectual life from approximately 1568 to 1840. [67] Not surprisingly, two figures that loom especially large in Tsunoda’s works are Hattori Nankaku and his mentor, Ogyū Sorai.

Tsunoda’s accounts of Edo mantic practice appear in six entries of the Accounts of Recent Times and seven of its sequel, ranging from astronomy/astrology to physiognomy, musical analysis, five agents calculations, and even the tasting of prepared food to reveal the origins of its ingredients and the gender of the cook. [68] In one entry, Tsunoda applauds Asada Gōryū’s 麻田剛立 (1734–1799) achievements in astronomy and calendar-making. Asada studied these difficult subjects by poring over all kinds of books and then testing this written knowledge against the results from his personal observations. He worked so hard that “for nine years his head did not not touch the pillow” (頭不觸枕九年). After another ten years of fine tuning, the calendar he constructed had reached such levels of refinement that it could forecast astronomical phenomena “without the slightest deviation” (毫髮無爽). Later, some Chinese merchants brought him two Western calendars, the contents of which fit Asada Gōryū’s system in "perfect harmony" (若合符節). Still, there were two separate methods, one for extrapolating the “waxing and waning [of the moon]” (shōchō 消長) and the other for “forecasting eclipses [of the sun and the moon]” (kyūshoku 求食), which only Asada Gōryū was able to master. Even Westerners could not reach his depth of understanding. [69] Nonetheless, as Tsunoda Ken notes, Asada Gōryū contributed primarily on the technical level, and he had to wait for another astronomer, Hazama Chōgai 間長涯 (a.k.a. Hazama Shigetomi 間重富, 1756–1816), to offer theoretical interpretations that explained his methods. [70] These accounts all suggest a tendency in Japan to combine traditional mantic practices with more modern scientific knowledge, a growing intellectual trend in the Edo period.

V. Women, Gender, and Divination

The Shishuo covers six hundred or so historical figures, from the Late Han to the end of the Wei-Jin period (from approximately 150 to 420 CE). Of these individuals, about one hundred are women, most of them portrayed in the chapter titled “Worthy Ladies” (Xianyuan 賢媛). Zhuangzi’s notion of the Perfected Person served as the model and spiritual resource for the xianyuancategory, exemplified by Wei-Jin women who possessed literary and artistic talents, broad learning, intellectual independence, moral strength, and good judgment. These women, as the Shishuoindicates, were full participants in character appraisal, whether they were evaluating others or being evaluated themselves. In this capacity, xianyuan often assumed an inordinate influence over both family and state affairs.

For example, Lady Han 韓, wife of the Jin gentleman Shan Tao 山濤 (205–283), was highly regarded at the time for “possessing the ability of recognition” (you caishi 有才識). [71] Here shi (識) is obviously a contraction of renlun jianshi (人倫鑒識) or character appraisal. The following episode, taken from the chapter “Xianyuan,” reveals Lady Han’s talent in this respect:

The first time Shan Tao met Ji Kang [223–262] and Ruan Ji [210–263], he became united with them in a friendship “stronger than metal and fragrant as orchids.” Shan’s wife, Lady Han, realizing that her husband’s relationship with the two men was different from ordinary friendship, asked him about it. Shan replied, “It's only these two gentlemen whom I may consider [true] friends [during] my mature years.”

His wife said, “In antiquity, Xu Fuji’s wife also personally observed Hu Yan and Zhao Cui. [72] I’d like to take a peep at these friends of yours. Is it all right?”

On another day, the two men came, and Shan’s wife urged him to detain them overnight. After preparing wine and meat, that night, she made a hole in the wall, and it was dawn before she remembered to return to her room.

When Shan came in, he asked her, “What did you think of the two men?” His wife replied, “Your own [talent and taste (caizhi 才致)] are in no way comparable to theirs. It’s only on the basis of your [recognition and judgment of human character types] (shidu 識度) that you should be their friend.”

Shan said. “They, too, have always considered my judgment to be superior.” (19/11) [73]

山公與嵇、阮一面,契若金蘭。山妻韓氏,覺公與二人異於常交。問公, 公曰:“我當年可以為友者,唯此二生耳!”妻曰:“負羈之妻亦親觀狐、 趙,意欲窺之,可乎?”他日,二人來,妻勸公止之宿,具酒肉。夜穿墉以視之,達旦忘反。公入曰:“二人何如?”妻曰:“君才致殊不如,正當以識度相友耳。”公曰:“伊輩亦常以我度為勝。”

Here we see that Lady Han is clearly an extremely capable exponent of Wei-Jin character appraisal. In the case quoted above, the persons evaluated by Lady Han were none other than the three leading figures of the Wei-Jin gentry: Ji Kang 嵇康, Ruan Ji 阮籍, and Lady Han’s own husband Shan Tao. Significantly, Shan Tao was considered to be the most prominent scholar of character appraisal of his time, and, for this reason, he was appointed to head the personnel selection bureau. [74] Yet, even he sought his wife’s judgment concerning the character of his friends.

As evaluators, women’s competence also appears in their use of explicitly mantic methods to assess personalities. For example, when Wang Ji 王濟 (ca. 240–ca. 285) is seeking a good match for his sister, his mother, Lady Zhong (Zhong Yan, 鍾琰; mid-third century), [75] demands to see the candidate. Thereafter, she comments:

This boy’s ability is adequate to raise him above the crowd. However, his background is humble, and if he doesn’t have a long life, he’ll never get to exercise his ability or usefulness. Observing his physiognomy and [bone] structure (xinggu 形骨), it’s evident that he won’t live to an old age. You may not contract a marriage with him.

此才足以拔萃,然地寒,不有長年,不得申其才用。觀其形骨,必不壽,不可與婚。 (19/12)

To Lady Zhong’s credit, the Shishuo recounts that “as it turned out, in a few years, the [boy] died.” In this case, and in many others, Shishuo stories about the participation of Wei-Jin women in character appraisal involve some form of physiognomic analysis in the ontological and metaphysical quest for knowledge about human nature. [76]

As mentioned previously, the mantic practices in Tang Shishuoti works often had to do with augmenting or invigorating imperial authority. In the New Account of the Great Tang, Liu Su provides a revealing illustration of the principle of “hailing the ruler and humbling the subject,” referencing the case of Empress Wu Zetian – the only woman in Chinese history ever to declare herself an emperor. Later historians have usually portrayed Wu Zetian as an aggressive, self-indulgent, and self-promoting woman, accusing her of usurping the divine imperial throne, like “a hen crowing at dawn” (pinji sicheng 牝雞司晨). [77] Liu Su tells us that her ambition was in fact predicted and encouraged by Tang gentlemen from the very beginning.

When Wu Zetian was barely a toddler, a gentleman named Yuan Tiangang 袁天綱 (ca. 583-ca. 665) who was skilled in physiognomy, paid her family a visit:

At that moment, Zetian, dressed like a boy, was carried out by her wet nurse. Tiangang was astonished to see her, saying: ‘This young boy’s spirit and expression look profound and pure, not easy to fathom.’ He asked her to try walking [xing 行], saying: “He has dragon eyes and a phoenix neck, extremely distinguished.” He then observed her from various angles, saying: “If this were a girl, she would become the Son of Heaven.” [78]

則天時衣男子服,乳母抱出,天綱大驚曰:“此郎君神采奧澈,不易可知。”試令行,天綱曰:“龍睛鳳頸,貴之極也!”轉側視之,“若是女,當為天子。”

Gender ironies suffuse Yuan Tiangang’s observations of the future female sovereign. He mistakes Wu Zetian for a boy but notices something unfathomable about her. After evaluating her face, body and movements, he detects in her one feature common to royal males – dragon eyes – and one common to royal females – a phoenix neck. Hence, he pronounces this androgynous being to be “extremely distinguished,” suggesting that if she were a female and would "act," she would become an emperor. [79]

Throughout the New Account of the Great Tang, Liu Su overlooks gender differences, equating Wu Zetian with other Tang emperors, always referring to her by her imperial title, Zetian, or simply shang 上 – Her Majesty. In Liu’s accounts of the conversations between the empress and her subjects, she uses the royal pronoun zhen 朕, and her subjects address her as tianzi 天子 (Son of Heaven); jun 君 (My Lord); bixia 陛下 (Your Majesty); and so forth.

Later Shishuo ti works continue to feature strong-minded, self-sufficient literate women who participate in mantic practices primarily through their evaluation of men. Among the numerous Ming-Qing Shishuo tiworks, two are devoted exclusively to women, and both are titled Women’s Shishuo (NüShishuo 女世說). The two authors, Li Qing 李清 (1602–1683), a man, and Yan Heng 嚴蘅 (1826?–1854), a woman, each endeavored to establish an explicitly female value system. At the center of this joint venture were two pivotal symbolic elements associated with the female body, the “milk” of women’s nurturing virtue and the “scent” of women’s literary and artistic talents. [80] Yan Heng’s unfinished work does not discuss women’s divinatory practices, but Li Qing registers thirty-two related episodes in his chapter on “Omens of Strangeness” (“Zhengyi” 徴異), which he considered to be equivalent to the category of “Technical Understanding.” [81]

Li Qing opens this chapter with a combination of milk and scent values in a story about Meng Jiang 孟姜. This brave young woman embarks, we are told, on a ten thousand-li (roughly three thousand-mile) journey to look for her husband among the slave-laborers drafted by the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (Qing shi huangdi 秦始皇帝) to build what would become the Great Wall. In the process of preparing to make winter clothes for her husband, Meng Jiang touches the bamboos in her courtyard with a needle and their leaves emit silk (#1). [82] Bamboo is associated explicitly with the “Bamboo Grove aura” 竹林風of the Shishuo tradition, and it serves in particular as a trope for xianyuan (although used by Li Qing here in an achronological way since the historical Qin shi huangdi lived much earlier than the Wei-Jin period). [83] That bamboo leaves could miraculously produce silk manifests the will of Heaven to assist the virtuous and talented Meng Jiang in her efforts to protect her husband from the effects of the brutal policies of the First Emperor. This episode frames the entire “Omens of Strangeness” chapter as a collective gallery of virtuous and talented women who protect people and culture with Heavenly blessing and help.

The following three stories of divination, dreams and omens reflect Li Qing’s effort to link the capacity of talented women to generate cultural products with their role in bearing children:

Once, Ren Fang’s [460–508] mother, née Pei, was taking a nap during the day, and dreamed of a five-colored canopy with bells hanging from its four corners falling down from Heaven. One of the bells dropped into her belly. Startled, she thus [became] pregnant. The diviner predicted, “You’ll certainly bear a talented son.” Later, she gave birth to Ren Fang, indeed a person of talent. (#9) [84]

任昉母裴氏,常晝臥,夢有五色彩旗蓋,四角懸鈴,自天而墜。其一鈴落入懷中,心悸,因有孕。占者曰:“必生才子。”後生昉,果有才。

Niu Su’s [fl. early 9thcent.] daughter Yingzhen used to dream of making books and then eating them. Every time she dreamed of this, she would eat several dozen volumes (juan 卷), and her writing style would change after she woke up. After several dreams like this, she became well versed in rhyme-prose, eulogy, and literary essays. (#24) [85]

牛肅女應貞嘗夢製書食之。每夢食數十卷,則文體一變。如是非一,遂工賦、頌、文。

A daughter of the Ding family was good at womanly work. On every Double Seventh Day, she would celebrate [the legend of the Weaving Girl] with wine and fruit. Once, she saw a meteor fall onto the ceremonial table. On the following day, she saw a golden shuttle for a weaving loom on a melon, and her ingenious ideas became much improved. (#27) [86]

丁氏女精於女紅,每七夕,禱以酒果,忽見流星墜筵中。明日瓜上有金梭,自是巧思益進。

All three stories share a similar omen-related narrative structure, and all three suggest Heaven’s special favor for talented women.

Although a rigorous cult of chastity existed in late imperial China (which, among other things, strongly discouraged remarriage by widows), Li Qing recorded two such remarriages, each of them provoked by a peculiar omen. In the first case, Née Yin’s 尹 husband passed away and her father advised her to remarry. Yin pointed to the iron rail of a well, swearing: “I’ll do so only if yellow orchids grow on it!” This indeed happened three years later (#7). [87] In the second case, under similar circumstances, Wu Shuji 吳淑姬 swore that she would not remarry unless her broken jade hairpin could be restored into a single piece. One day, after reading the poetry of a scholar named Yang Ziye’s 楊子冶, she decided to buy a volume of his poetry for herself. Preparing to go out, she opened her jewelry box and saw that the two pieces of the broken hairpin had already come together. She sent the hairpin to Ziye, and the two became husband and wife (諷而愛之,購得一卷,啓匲視簮,已合,遂以寄子冶,結爲夫妻) (#26). [88]

In these two episodes, flowers and a jade hairpin are metaphors for talented women who yearn for the companionate love life denied to most widows in Qing China by the strict and “unnatural” rules imposed by the so-called cult of chastity. Their implicit wishes are granted by Heaven, showing that this cosmic entity, as the Shishuo affirms, embraces the Way (Dao) of the Natural. Wu Shuji’s case in particular highlights the theme of a woman who seeks happiness on her own terms, and whose wish for a companionate marriage finds its expression in the couples’ common love of poetry.

By the same token, Heaven favored aesthetic values to such an extent that it would break the very bottom line of gender segregation, allowing a woman to visit a man at night for poetic and artistic communication and cooperation. [89] Li Qing records several such cases. One story tells of the famous Liang 梁 (502–557) poet Shen Yue 沈約 (441–513) sitting alone on a rainy night. Suddenly,

the wind blew open the bamboo door. A woman with a reeling tool walked in and sat down [without being invited]. The wind blew the rain like silk threads. The woman reeled the rain threads ceaselessly with the wind. Whenever the thread was broken, she would use her mouth to tie it up as if tying real silk. Before the candle burned out, she had reeled several ounces. She then stood up and gave the silk to Yue, saying: “This is called ice silk, for you to make ice brocade.” Suddenly, she disappeared. Later, Yue wove the silk into a piece of brocade. Fresh, pure, and luminous, it looked no different from ice. (#11) [90]

風開竹扉,有一女擕絡絲具,入門便坐。風飄細雨如絲,女隨風引絡,絡繹不斷,斷時亦就口續之,若真絲焉。燭未及跋,得數兩,起贈約曰:“此謂冰絲,贈君造為冰紈。”忽不見。 約後織成紈,鮮潔明淨,不異于冰。

Although this story is not concerned with divination or omens, it reveals a woman who could serve as an agent of Heaven in the interest of nurturing a male poet. The mysterious visitor reels the quintessence of nature – synthesizing it with her own saliva, the female essence – into a silk yarn, then asking a talented male to continue the woman’s job, weaving the silk into a piece of fabric. This mysterious act, freely crossing the boundaries between heavenly and human worlds, male and female, womanly work and men’s literary creation, produces an ice brocade that resembles in its magical and ethereal beauty the Spiritual/Perfected Person in the Zhuangzi.

In another Women’s Shishuo episode, a young lady pays a nighttime visit to a male musician in order to teach him a zither melody long lost after Ji Kang’s execution by the Simas during the Wei-Jin transition (See Shishuo 6/2). Upon taking her leave, the woman tells the man that the melody is not for entertaining a vulgar audience, but for him to enjoy by himself in seclusion (#14). [91] In this episode, the woman operates as an agent of culture, trying to fill in a missing piece that men have brutally severed from history. Although an unmarried woman was not supposed be alone with a man, much less spend the night with him, a shared love of poetry and art, as well as a common appreciation of pure spirit, might justify such an intimate gender-crossing relationship.

This female tradition of mystical experiences and unorthodox practices continues to appear in later Shishuo ti works. One story in the chapter on “Technical Understanding” in the New Shishuo involves Huang Jiangang 黃建剛, a late Qing “Confucian” who acquires the ability to hypnotize people while traveling in Europe. Returning home, he tries out the technique in order to exploit women for immoral purposes, and is chased away from his hometown. He settles down with his wife in a Miao minority region in southwestern Hunan, where he resumes his exploitation of women. Representatives of the Miao people travel all the way to Guizhou province to seek help from a local patriarch, who in turn sends a female disciple to oppose Huang. Hearing this, Huang laughs, remarking: “I come from a civilized country; what is there to fear from these [Miao] barbarians?” (我自文明國來,奚憚此野蠻者). But

one morning after Huang got up, and his wife was applying her makeup, a handsome youth waved to her and she absent-mindedly walked [off] alongside him. Huang urgently followed them, only to see the two, hand-in-hand, walking as fast as the wind, whereupon they soon disappeared without a trace. Huang came back feeling despondent, and found the two of them in each other’s arms in the room. Extremely angry, Huang pointed his finger at the youth and the youth looked back at him [in a threatening way]. Huang felt the youth’s chilly glare penetrating into his hair like an arrow and making him dizzy. Knowing that he was about to fall into a trap, Huang tried hard to maintain himself. He noticed the youth’s eyes had dimmed, as if they had encountered heavy layers of barricades. The two thereupon competed with each other for about an hour. Finally, the youth clapped his hands and laughed, saying: “Your skill is indeed outstanding, but now what?” Huang retreated to a couch, unable to speak. While the youth was laughing, Huang saw dimples emerge on the youth’s cheeks, giving the appearance of a girl. Huang suddenly realized [that it was, indeed, a girl]. No longer able to stand up, Huang could only watch the young woman leave, [an experience from which he] did not recover until noon. (#30) [92]

一日,晨起,妻方曉妝,有美少年向之招手,妻不覺從之行。黃亟逐之,兩人挽臂行如風,頃刻不見。喪氣而歸,則妻方與少年交頸於室也。大忿,急以手指少年,少年亦以目視黃。黃覺少年目光,冷射毛髮,幾欲眩暈,知將中術,爰力持之,手不能擧,勉為支持。視少年亦目光黯淡,如嬰重困者。於是彼此互競,若一時許,少年拍手笑曰:“君術真高,今如何?”黃不覺退居榻下,口噤不能聲。少年笑時,梨渦生頰,儼然一女郎也。黃大悟,然不能起,目送其去,日午乃蘇。

This episode epitomizes the kinds of conflict that occurred with increasing frequency during the tumultuous late Qing period – struggles between the self and “the other,” between China and the West, between “civilization” and “barbarism,” and between women and men. Ironically, in Huang’s situation, China and the West came to be conflated in a certain limited sense. On the one hand, he was a Confucian patriarch, a representative of China’s civilized culture. On the other hand, he had traveled to Europe, where he had learned a powerful foreign technique, hypnotism, which in turn empowered him.” [93] With this doubly “civilized” self, Huang dared to bully women – firstly Han Chinese, and then Miao people. But, in this case, the “barbarians” had the last laugh: a young Miao girl first humiliated Huang and then she defeated him in “battle.” [94]

Not surprisingly, JapaneseShishuo imitations record women’s participation in mantic practices. One “Technical Understanding” episode in AnAccount of the Great Eastern World tells the story of a woman physiognomist. Before the Heian aristocrat Fujiwara no Michiaki 藤[原]道明 (fl. early 10th century) rose to statesmanship, he once went to the market with his wife. They disguised themselves as commoners and walked separately. At one point, they encountered an old lady. She saw the wife first. Looking at the face of the wife, the old lady predicted that the woman would be the wife of a vice prime-minister. The old lady then looked at Michiaki. She pointed at him, saying to the wife: “You should marry this man, because he has distinguished facial features” (亦[宜]配此人貴相也) (#6) [95].

The Continued Accounts of Recent Times includes in its chapter on “Worthy Ladies” a story about another woman physiognomist – the elder sister of the Edo Confucian scholar Nakanishi Tan’en 中西淡淵 (1709–1752). According to this tale, a man who had declared that he would avenge his father’s death came to visit Tan’en. Observing the visitor, the sister commented to her brother: “This man is not one capable of revenge. I see that he has long fingers and wears untidy shoes” (此必不能復讎者。吾見其爪長,置履不整). As predicted, the man never fulfilled his promise, and lived a rather mundane life selling tobacco (#9) [96].

VI. Concluding Remarks

More work remains to be done on the relationship between elite literature and popular divination in China and Japan (not to mention the rest of East Asia), but, as I have tried to indicate in this preliminary study, the subject is rich with possibilities. And even if we focus solely on works of the Shishuo genre, it is clear that mantic practices in both cultures constituted an integral part of the longstanding social and psychological phenomenon known in Chinese as renlun jianshi 人倫鑑識, or character appraisal. Although character appraisal originally grew out of the very specific circumstances of social and intellectual life in Wei-Jin China, it evolved over time and across space in revealing and significant ways.

To be sure, many of the general categories of concern in Shishuo ti remained the same, but a number of new ones were invented in response to the values and sensibilities of different authors. Moreover, even within the older categories, important changes took place over time – changes inspired by different political, social, intellectual and cultural circumstances. This was particularly true, of course, when the Shishuo genre traveled to Japan from China and became domesticated in various ways.

Finally, because the genre was founded on the ideal of the androgynous Perfected Person, gender equality was always a central concern of the Shishuo ti. As we have seen, focusing on these works helps us to appreciate that even under circumstances of social discrimination or difficulty (such as the problems created by the onerous cult of chastity in late imperial China), women, invariably informed by skill in character appraisal, played multiple and often unconventional roles in both China and Japan, divining in a great many creative ways and giving valuable advice to both men and women (often facilitated by divination). When necessary, they also proved to be worthy adversaries of men.

Nanxiu Qian, M.A. Nanjing University, Ph.D. Yale (1994), Professor of Chinese Literature at Rice. Her research interests focus on classical Chinese literature, women and gender studies, and the Sinosphere studies. She has published broadly in English and Chinese, including such as Politics, Poetics, and Gender in Late Qing China: Xue Shaohui (1866-1911) and the Era of Reform(2015), and Spirit and Self in Medieval China: The Shih-shuo hsin-yu and Its Legacy (2001).

[1] This article is revised from my paper for the Conference on “Divinatory Traditions in East Asia: Historical, Comparative and Transnational Perspectives,” Rice University, February 17-18, 2012. Great thanks to Professor Richard J. Smith for his thorough comments and suggestions, and to Ms. Amber Szymczyk for her editorial help. Unless otherwise stated, all translations are mine.

[2] Richard J. Smith, Mapping China and Managing the World: Culture, Cartography and Cosmology in Late Imperial Times (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), 151.

[3] For this term and its significance in East Asian culture, see the report on the international conference “Reconsidering the Sinosphere: A Critical Analysis of the Literary Sinitic in East Asian Cultures,” Rice University, March 30–April 1, 2017 at http://sinosphere.rice.edu/.

[4] For background, see Liu Yiqing, Shishuo xinyu [jianshu] 世說新語箋疏 ([Commentary on the] Shishuo xinyu), commentary by Yu Jiaxi 余嘉錫 (1884–1955), 2 vols. (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1993); trans. Richard B. Mather, A New Account of Tales of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976). For the connections between the Wei-Jin Xuanxueand the Shishuo xinyu, see Nanxiu Qian, Spirit and Self in Medieval China: The Shishuo hsin-yü and Its Legacy (Honolulu: The University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), chapters 1–3.

[5] E. Zürcher, The Buddhist Conquest of China, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 1959), 1:46.

[6] See ibid.

[7] For the connections between Wei-Jin Xuanxue and character appraisal, and a study of the Shishuo ti tradition, see Qian, Spirit and Self in Medieval China.

[8] See Zhuangzi [jishi] 莊子[集釋] ([Collected commentary on the] Zhuangzi), “Xiaoyao you” 逍遙游 (Free roaming) commentary by Guo Qingfan 郭慶藩, 4 vols. (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1961), juan1A, 1:17; trans. see also Burton Watson, The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968), 32.

[9] Ibid., juan 1A, 1:28; trans. Watson, The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, 33, modified. Cheng Xuanying’s 成玄英 shu 疏 commentary on the Zhuangzi“Xiaoyao you” points out that the zhiren, the shenren, and the shengren 聖人 (Sage) “are in fact one” (qishi yiye 其實一也); ibid., juan1A, 1:22.

[10] Zürcher, The Buddhist Conquest, 1:123.

[11] Zhi Dun, “Da Xiao ping duibi yaochao xu” 大小品對比要抄序 (Preface to a Synoptic Extract of the Larger and Smaller Versions [of thePrajñāpāramitā]), in Seng You僧祐 (445–518), Chu Sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集 (Collected bibliographic records of Buddhist scripts and treatises) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1995), juan 8, 300–301. For Wei-Jin understanding of the function of shen, see Qian, Spirit and Self in Medieval China, 152–55. Zhi Dun may also have incorporated the quality of the Confucian Sage from the “Zhongyong” 中庸 (the mean), which maintains that the Sage, being the “most sincere” (zhicheng至誠), is capable of predicting the future (qianzhi 前知) - the rise and fall of the state, and the good and the bad fortune of a person; see Liji [zhengyi] 禮記[正義] ([Orthodox commentary on] The record of ritual), “Zhongyong,” zhu 註 commentary by Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200), shu 疏 commentary by Kong Yingda 孔穎達 (574-648), in Ruan Yuan 阮元 (1764–1849) ed., Shisanjing zhushu 十三經註疏 (Commentaries on the thirteen Chinese classics), 2 vols. (1826; rprt. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1979), juan 53, 2:1632.

[12] Citation of the Shishuo xinyu will be quoted from the Shishuo xinyu [jianshu] and marked by chapter number/episode number; trans. Mather, A New Account of Tales of the World, 196, modified.

[13] Liu Jun’s commentary on Shishuo xinyu, 7/1.