A version of this paper was presented at “From Area Studies to Transregional Studies? Contours of Globalization in Asia’s Re-Integration,” an international symposium held at the University of Iowa’s Center for Asian and Pacific Studies in 2010. I would like to thank symposium organizer and host Sonia Ryang for inviting me to participate, and the other participants for their comments.

In 2005, I watched a performance by Osaka rock band Nine at a live music club in Seoul. Between songs, lead singer Shibata Takenori talked about his background, speaking smoothly in Japanese and Korean, while occasional switching to English. He uses all three languages on his website, too, expressing his feelings as a Japan-born person of Korean descent. I mention Nine, not only because Shibata himself represents one type of transnationalism, but also because the audience that night in Seoul was composed almost entirely of young women. The Korean women thronging around the stage were joined by adoring female fans from Japan, all following the handsome lead singer’s every move, applauding and yelling out encouragement at various points. The young women from both countries were dressed in similar clothing, their make-up and hairstyles reflecting shared concepts of beauty. Japan-based indie bands such as Nine usually fly below the radar when it comes to the international “Cool Japan” image promoted by the Japanese government and the corporate culture industry. During Nine’s performance, it was clear, however, that the band enjoyed a solid female support base in at least two countries. In this essay, I hope to draw attention to this minor variety of Asian transnationalism, the cross-border sharing of girl culture.

Girl culture and girl spaces are worthy of interest not only because of their economic potential, but also for what they can tell us about contemporary gendered preoccupations and activities. I do not use the word “girl” to indicate a chronological category, but instead to denote a youth-oriented, feminine cultural focus, a state of mind or “girl consciousness” (Takahara 2006). Scholars who study girl cultures are careful to balance interpretations that recognize both agency and oppression by noting “the power, agency, and complicity of girls in resisting and negotiating oppression and inequality within the matrices of structural forces that constrain, impose limits on and contribute to [girls’] vulnerabilities” (Jiwani, Steenbergen, Mitchell (2006:x). Transnational East Asian girl culture reflects this tension, at times appearing to conform to mainstream values, at other times resisting them.

With my focus in this paper restricted to East Asia due to the limited nature of my own experience, I examine this region as one that includes a variety of girl spaces that enable the creation of new forms of transnational female-oriented cultural expression and activity. I find Michael Smith’s (2005) concept of “transnational urbanism” very useful when thinking about girl culture, which he defines as “the socio-cultural and political processes by which social actors forge connections between localities across national borders that increasingly sustain new modes of politics, economics, and cultures” (Smith 2005:5). I believe that there are several cross-border urban spaces in which girls consume and create a common girl subjectivity. In addition to music clubs, these include neko cafes (with patrons visiting the kittens who live there), purikura (print club sticker booth) arcades, nail salons, aesthetic salons, bead stores, fabric shops, cosplay conventions, fortune-telling booths, tourism venues, and other spaces catering to the interests and aesthetics of female consumers.

My interest lies in looking beyond globalization as an economic or political process to consider how local subjects themselves shape transnational trends. East Asia is dependent on the female consumer, as well as the types of femininity constructed through girls’ consumption of a shared interregional beauty culture that encompasses fashion and the media. I urge scholars to extend their understanding of East Asia beyond the level of political structures, economic organizations, and officially-endorsed notions of coolness to include and acknowledge locally consumed and performed examples of female culture. By considering activities and media forms that are not entirely contained within national borders nor approved of by older male members of particular societies, I hope to raise awareness about the content, creation, and global reach of girl culture.

East Asia as a Region

Some optimistic scholars have put forth a proposal for a “Draft Charter for an East Asian Community” along the lines of the European Union (Nakamura 2008). Tamio Nakamura, for example, claims that, unlike in the case of Europe, “the definition of ‘East Asia’ hinges more on economic and political purposes than on precise geography” (Nakamura 2008: 4). The creators of this charter envision that it will serve as an agreement between nations promoting the resolution of economic and security issues. Apart from failing to include any specific reference to the need to rectify wartime injustices, the charter also reflects a kind of thinking that overlooks unequal power relations between men and women throughout the region. The proposal not only ignores the fact that trafficking in women continues, but also neglects to draw attention to the exploitation of female labor that has enabled economic expansion. Although a well-meaning initiative, the charter is completely gender-blind, leading me to follow the pioneering example of Cynthia Enloe, renowned for her many decades of research in the field of international politics, posing the question, “Where are the women?” As she notes, empires, and, by extension, cultural entities, are not simply forged in the “gilded diplomatic halls, the bloody battlefields, and the floors of stock exchanges” (Enloe 2004: 269-70). Common culture is also found in girl spaces such as game arcades, shopping malls, nail salons, fortune-telling booths, and live music clubs where bands like Nine perform.

Perhaps, in noticing girl culture and girl spaces, we may be able to trace the contours of one manifestation of what might be defined as transnational East Asia. What I am asking is that when we consider transnationalism, we include a hidden or trivialized layer of female consumers who have forged a type of commonality and a shared construction of femininity. Global products are designed and promoted with this group in mind (all of those cute things!) It is also the target for the intense marketing of idealized concepts related to beauty and normative femininity. I am proposing the concept of “girl culture” in order to capture this layer, one that cuts across national borders. I am limiting this preliminary investigation to East Asia, although other scholars have been tracking specific examples of transnational popular culture throughout Asia as a whole. Examples include research concerning the spread and popularity of Korean television dramas throughout Southeast Asia, the consumption of Japanese manga in Malaysia, and the spread of East Asian concepts of beauty to Thailand (Kim 2017; Abraham 2010; Kang 2017). There is also “hijab cosplay,” a form of costume play carried out without the participant having to remove her hijab, commonly found among girl culture fans of Japanese media in Indonesia and Malaysia (Rastati 2015). During my visits to Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, I have often encountered examples of girls creating shared energy, as well as shared aesthetics and values, of a kind typically neglected by scholars when they talk about East Asia as a region. Because these activities are usually denigrated as silly, wasteful or childish, this new variety of transnational girl culture is rarely seen as worthy of attention. Certain scholars or academics might also react in a dismissive manner to this paper’s scholarly focus on girl culture, sneering that this is an inappropriate subject for research. I often face this type of response from academics, especially those from Japan, when I tell them about my research on the beauty industry or the fortune-telling industry. [1]

While girls are a force behind many types of consumption, they are often overlooked due to the feminized nature of the culture industries that are most often associated with them, such as fashion, beauty, craft-making, and fortune-telling. Scholars often talk about the intensive and transregional way in which ideas, goods and technologies are exchanged and communicated throughout Asia, yet they do not always say how this process might be gendered. I want to discuss a few examples of girl culture that, while having been integrated into female life across the region, are rarely seen as elements of a shared culture. This transnational female urbanism sometimes thrives outside male-driven and ideologically-driven notions of Asian “coolness.” Before turning to specific examples, I will discuss problems inherent to the ideology of “Cool Japan,” a concept that differs from my notion of transnational girl culture.

Not Otaku Japan

The ubiquitous nature and narrative power of the “Cool Japan” promotional campaign mean that scholars are obliged to at least wave a hand in its direction, but I want to distinguish my description of East Asian girl culture from its intent and focus. The Japanese government began to seriously promote an in-house version of coolness in 2002, based on the influential concept of soft power – the idea that states are able to use their creative industries as a vehicle for global diplomacy (Nye 1990). The exuberant blitz of “Cool Japan” products and events, with their special focus on anime, manga, game software, and film, led many people to ask questions about the basis for this campaign. What criteria were being used by government bureaucrats in determining suitable cool content for export? [2] Should a government curate creative output and decide what is appropriate for promotion and export? One special problem associated with Cool Japan is that it conceals the gendered nature of contemporary culture industries. Cool Japan is largely dependent on the global male interest in comics, animation, and games featuring girls and women as erotic objects of interest (Miller 2011). The otaku (nerd), once the tarnished symbol of a Japan gone wrong, has become a driving force in the reification of Cool Japan. This type of male-determined nationalism positions the interests and perspectives of the male viewer at the core of the Cool Japan ideology. The genesis of the government-sponsored Cool Japan is usually attributed to Asō Tarō during his period as Foreign Affairs Minister (2005 to 2007; he later served as Prime Minister from 2008 to 2009). Asō is a long-standing member of the ultra-nationalist lobby known as Nippon Kaigi (founded in 1997). Nippon Kaigi is actively involved in the promotion of many right-wing views and revisionist initiatives, including measures aimed at limiting freedoms enjoyed by women (Mizohata 2016).

While some aspects of Cool Japan overlap with East Asian girl culture, especially in the domain of cute aesthetics, the two are undeniably different. Girl culture is typically given very little space in the global promotion of Cool Japan, which is dominated by a male-oriented ethos. Government efforts are paralleled by the activities of fans and private entrepreneurs promoting global consumption. Key images and details thought to be excessively imbued with cultural or historical references are sometimes excised by translators or publishers in the case of media products marketed to non-Japanese consumers. Hired specialists prepare translated versions of cultural products in preparation for their release overseas, scanning them for content that foreign consumers might find offensive or difficult to process. When it comes to the girls of East Asia and the cultural products they seek out and consume, however, anything goes. While the media companies selling Cool Japan (or its Korean equivalent, Hallyu) in other parts of Asia are making decisions about the content of particular products prior to their official export based on their assumptions concerning the intended audience, girls in the region are accessing and consuming cultural forms that have not gone through this sanitizing process. Sharing content on the internet, they move around in a transnational manner, consuming content in urban spaces such as cosplay conventions and amateur manga shops.

The production and consumption of East Asian girl culture often takes place in spaces other than those planned for such activities, as well as in spaces where few might expect such activities to take place. This neglected stratum is manifested in ways that are hard to track, such as in particular kinds of language use, specific types of fortune-telling, graffiti on print club photos, or the creation of homemade costumes. In Korea, while elders tend to focus on historical and political disputes, young women actively borrow not only Japanese cultural forms, but also linguistic terms. Common examples of Japanese-to-Korean loanwords (as well as three-way loans from English to Japanese and then to Korean) include otaku (nerd), koseupeure (cosplay), rorita (Lolita fashion or subculture), nawabari (territory, stomping ground), kao (literally face, in the sense of bluff or show), and kanji (feeling, used to meaning cool style or looking good). I will briefly examine several examples of this phenomenon, considering the role played by each one in the context of transnational girl culture: print club photo stickers (purikura), BL (Boys Love) media, costume play (cosplay), and fortune-telling. [3]

Purikura

Image 1. Purikura arcade in Seoul. Photo by Brian Adler, 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

Purikura, an abbreviated form of purinto kurabu (print club), is a type of “selfie” in which photos are taken in a booth before being edited on a video screen and then printed out as tiny stickers (Miller 2003, 2005). In Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and China, girls manipulate the annotation capabilities of purikura machines in order to compose photo-textual artifacts that are discussed, critiqued and shared. The machines have become quite sophisticated in their ability to allow users to annotate photos with text, icons, decorations and props that reveal a certain level of expertise and creativity. The photo stickers have become an underground form of social commentary, taboo or transgressive words and poses often interspersed among seemingly sweet or innocent imagery. They are a vehicle through which girls are able to freely express their own attitudes or sense of ambivalence. Transnational girls have taken a familiar form of gender commodification, the female photograph used for male arousal, and used it for their own purposes.

The Japanese purikura machine achieved global popularity during the mid-2000s. Some firms outside Japan started manufacturing and selling their own machines, which are now found in train stations, game arcades and shopping malls in major cities throughout East Asia. In Taipei, they are most commonly found in Ximending, a district that is home to many youth culture-related stores and outlets specializing in manga and anime-related products imported from Japan. In Seoul, they are common in Myŏngdong, a shopping area frequented by young people (Image 1).

During a visit to Seoul in 2005, I observed a group of three friends completing a purikura purchase. They stood around analyzing the stickers, laughing and commenting on them. I have seen identical behavior in major cities throughout Japan and Taiwan. A shared culture of purikura production exists among the girls of East Asia. They often decide beforehand on the theme or intent of what they are about to create, deliberately selecting particular icons and text when annotating the photos, later analyzing and sharing the results, all the while planning their future efforts. In a similar manner to anthropologists, designers of purikura machines observe the behavior of users, constantly adding new editing features and icons to the machines.

Image 2. Sega flyer for a Halloween purikura in Taiwan, 2016.

Japanese purikura booth manufacturer Sega has tried to maintain its market share by hosting local websites and Facebook pages for female purikura enthusiasts in Taiwan and Korea. [4] On its Facebook pages, it announces sponsored events, such as holiday cosplay contests and holiday-themed special events (Image 2). The purikura machines found in Asia are most often frequented by two or more girls at a time, using the machines to memorialize their friendships and catch-ups. It is no surprise, therefore, that Sega and the other purikura machine developers place an emphasis on girl culture in their design and advertising.

BL (Boys Love) Media

In 2009, I met a young woman from China who was an exchange student at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. During a guest lecture, I happened to mention a subgenre of Japanese comics that is popular among girls and known as BL (Boys Love) manga. This type of comic, produced for a female audience, celebrates idealized homoerotic relationships between beautiful young men. The exchange student came up to me after my lecture, pressing me for my opinion on BL manga. When I replied that I found BL manga interesting and inoffensive, she breathlessly started recounting all of her favorite titles, explaining how they were read and circulated among many of her friends back in Beijing.

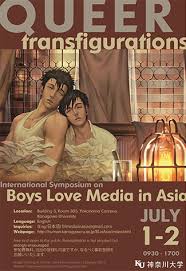

Image 3. Poster for BL conference at Kanagawa University in Yokohama, 2017.

The global popularity of BL media is acknowledged by a large scholarly community that is devoted to its study. Scholars investigate the ways in which BL genres, aesthetics and styles have been consumed and changed by female fans in transnational contexts. The growing body of literature on BL media includes a thesis by Li (2009) that examines erotic images found in Japanese BL manga and how these are appreciated among Mandarin-speaking Chinese communities, as well as research concerning transnational BL culture in Taiwan (Martin 2012). In addition, a comprehensive volume produced by McLelland, Nagaike, Suganuma, and Welker (2015) includes an overview of BL media, including its history and core texts, an exploration of the debates surrounding the genre, as well as fascinating ethnographic material concerning its consumption. In 2017, a scholarly conference entitled “Queer Transfigurations: International Symposium on Boys Love Media in Asia,” was held at Kanagawa University in Yokohama, Japan (Image 3). The conference featured twenty-three scholars from all over Asia who are involved in research related to BL media.

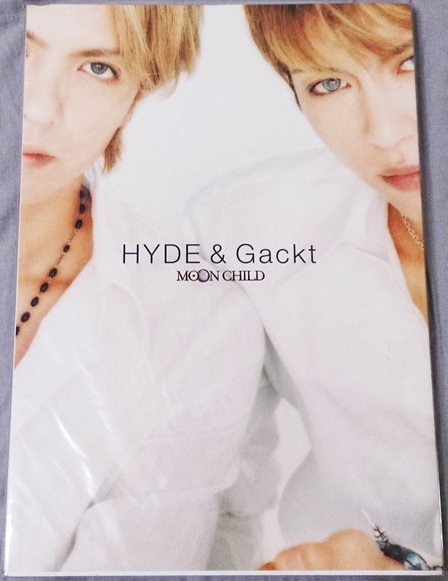

Image 4. Photographs taken of Hyde and Gackt from the set of the film Moon Child (Tsukagoshi 2003).

Female desire for BL content has also driven the production of several feature films that have achieved cult followings among girls throughout Asia. Most of these films were never popular with general audiences, but this does not seem to have been their objective. One, a major feature film called Onmyōji (Takita 2001), is set in the medieval Heian period (794 to 1185 A.D.), and features a Japanese wizard by the name of Abe no Seimei. Despite its lack of commercial success outside Asia, the film was appreciated by female audiences throughout East Asia. Together with a range of Seimei-related media products, including a TV series, anime productions, books, manga, and fan art, it served as the inspiration for thousands of pan-Asian cosplay ensembles and items of fan art. In line with its status as a core girl culture product, the film contains references to homoerotic attraction between the two leading male characters, thereby drawing in female fans of the BL genre. The film is based on a series of light novels by writer Yumemakura Baku, who has made it clear in interviews that he had the girl culture consumer in mind when he penned the stories (Miller 2008). American critics were dismayed that Onmyōji was not just another typical orientalist fantasy action film, failing to detect its purposely homoerotic subtext and intentional campiness.

Another film adored by female BL fans throughout Asia is Moon Child, a transnational vampire/gangster movie directed by Takahisa Zeze (2003). Shot in Taiwan, the movie stars J-Pop artists, Kamui Gakuto (who often uses the name Gackt), Takarai Hideto (a member of rock band L’Arc-en-Ciel who goes by the name Hyde), and Chinese-American actor Leehom Wang. Many scenes in the film suggest a homoerotic relationship between Gackt and Hyde. These scenes were most likely the reason for the film’s genesis, as its plot clearly points to an intention to appeal to BL-hungry female fans throughout transnational Asia. The film led to the production of other forms of popular media, such as a book that has become a transnational fetish item among girls throughout Asia containing 160 color photographs of the two beautiful leading actors taken during the filming of the movie (Tsukagoshi 200, Image 4).

Cosplay

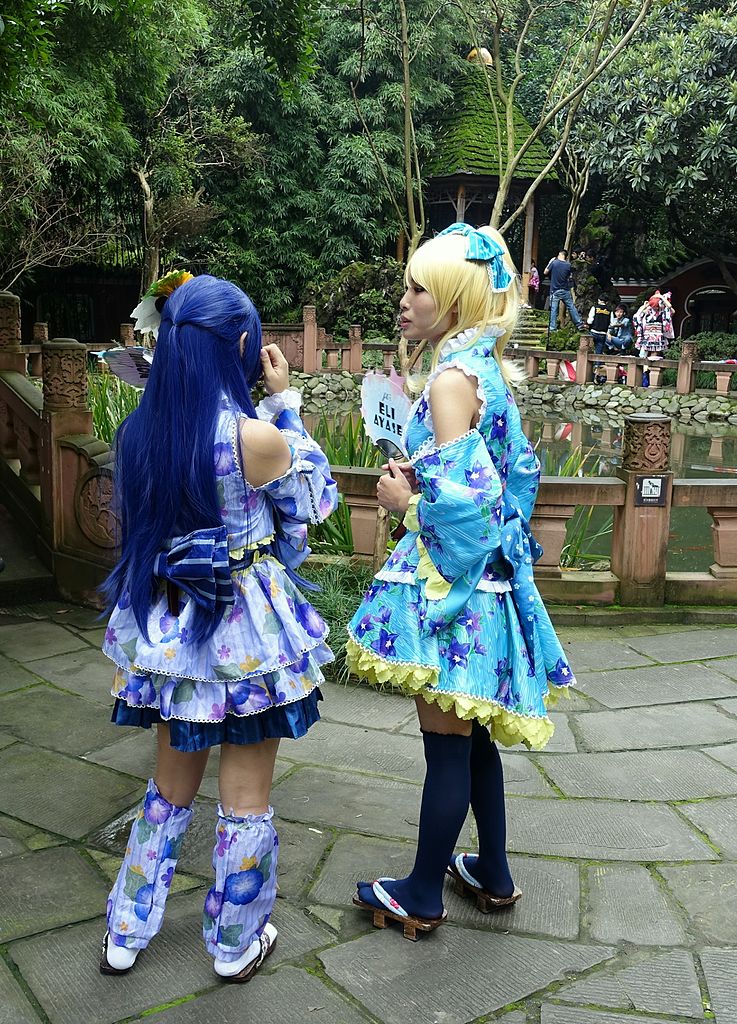

Image 5. Cosplay at Wangjian Lou Park in Chengdu, China. Photo by Daerot, 2015. Wikimedia Commons.

In tandem with the spread of manga, anime, and conventions that bring fans, producers and artists together is the practice of dressing up as a beloved character from the popular cultural media. In Asian girl culture, dressing up as a character taken from anime, game or manga origins has been enormously liberating and satisfying. The creative energy used in shopping for, sewing, embroidering, gluing, and putting together intricate costumes provides a unique sense of accomplishment (Image 5). Wearing the costumes, with their intricate or revealing aspects as well as their often astonishing accoutrements, such as blue wigs, bizarre weapons, and extreme make-up, has enabled productive individual expression of a type often lost under the weight of norms associated with school and workplace socialization.

Image 6. Kosupure Make magazine (Japan and Taiwan versions) (Cosplay Make 2016).

Although its content has been curated and is therefore selective in nature, one online website traces the consumption of girl culture in East Asia through a series of articles, interviews and photographs (Fukuoka Prefectural Government 2010). Young women in Taiwan, Korea, Hong Kong and China are interviewed about cosplay, kawaii (cute) aesthetics, Lolita fashion, J-pop music, manga, and more. A section entitled “Cosplayers Laboratory” includes a profile of each young woman, featuring her photograph, her cosplayer name, her birthday, as well as information concerning where she lives, her hobbies, how long she has been participating in cosplay, and her favorite anime or manga characters. For example, while Rie Rie from Busan in South Korea likes Japanese street fashion, food, and cosmetics, Iris from Taiwan is a Lolita, and Charlene in Hong Kong enjoys reading Japanese magazines and wearing Lolita fashion (Fukuoka Prefectural Government 2010).

Numerous cosplay magazines are published in Japan, with some of them translated and distributed elsewhere in Asia. For example, Taiwan has its own local version of Kosupure Make (Image 6). There are also locally published cosplay magazines, such as Taiwan’s bi-monthly Cosmore. Chang Mio, editor of Cosmore, notes that the magazine’s readers are primarily high school girls (Wang 2007).

Image 7. Flyer for Tenpyō Era (729~749) cosplay experience, Nara, Japan.

One interesting form of cosplay is related to international travel and tourism. Kyoto has capitalized on an interest in apprentice geisha, and numerous photography studios in the city offer cosplay experiences (Bardsley 2011). On numerous occasions, I noticed that many of the customers at one such studio in Kyoto Tower were young women from Korea and China. Capitalizing on its identity as the ancient capital of Japan, the city of Nara has also begun offering participation in a type of historical costume play in which customers are provided with Tenpyō Era (729~749 A.D.) costumes and hairstyling. A service offering participants souvenir photographs is also available (Image 7). The Tenpyō Era was noted for its avid adoption of continental culture, which was a product of immigration as well as a series of diplomatic and cultural missions to China. Chinese tourists visiting local historic sites dating from this period experience them as emblems of their own lost Tang culture. During fieldwork stays in Nara in 2015 and 2016, I noticed that many of the Tenpyō Era cosplay customers were female tourists from China. Groups of Chinese girls adorned in period costume could be seen promenading around the shopping arcades and historic sites of the ancient capital, occasionally trailing entourages of non-costumed family members or male attendants.

Fortune-telling

Image 8. Korean Wave-Inspired Face-Reading (Yanagi 2005).

Japan’s fortune-telling industry entered a period of intensification a few decades ago, occult pursuits becoming dominated by women and girls. This feminization led to girl culture aesthetics and interests coming to the fore, this emphasis manifested in a new range of fortune-telling services (Miller 2011b, 2014, 2017). Traditional fortune-telling practices, such as palmistry, face-reading, and Chinese-style astrology, were reinvigorated or creolized in order to increase their appeal, and an enormous variety of new and hybrid occult genres was also created. In addition, fortune-telling became the basis for a range of social and entertainment activities, including tourism. I will mention a few examples of how fortune-telling has also become part of transnational girl culture in Japan. One involves the introduction of Korean elements into local Japanese fortune-telling genres, while the other concerns the massive growth in fortune-telling tourism from Japan to other parts of East Asia.

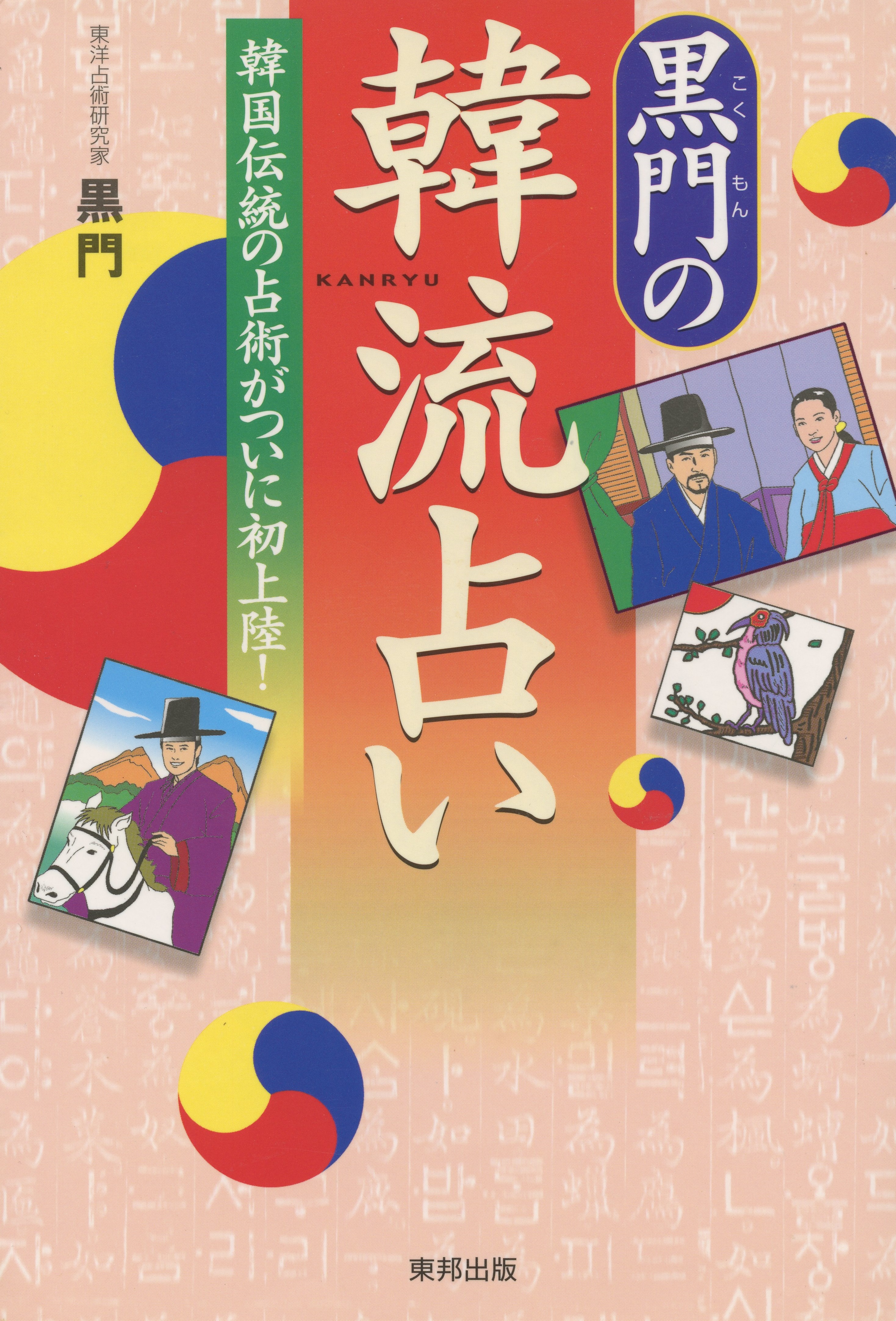

Image 9. Kokumon’s Korean Wave-Inspired Fortune-Telling (Takane 2006).

These new transnational forms of fortune-telling might stem from trends found in other domains of popular culture. For example, the avalanche of Korean TV dramas, films, cookbooks, and other media pouring into Japan from 2003 has been dubbed the “Korean Wave” (kanryū in Japanese; hallyu in Korean). A small but revealing example is the phenomenon of Korean Wave-inspired face-reading, described in a book by Watei Yanagi (Yanagi 2005, Image 8). Face-reading is an ancient practice that originated in China before being transmitted to the Korean peninsula and then Japan. Yanagi’s slim volume presents the faces of well-known Korean celebrities from TV dramas and films as examples of the different facial categories. The back of the book includes a section containing maps and specific information for readers wishing to visit fortune-telling spots in Seoul. Profiles of six different fortune-tellers include descriptions of each one’s expertise and where to find them. Some are associated with “fortune telling cafes” in Seoul, which are popular venues for the consumption of these services.

Takane Setsuo, a prolific writer who goes by the pen name Kokumon (Black Gate), is the author of another book dealing with Korean Wave-style fortune-telling. His book presents forecasts based on traditional Chinese astrology that are illustrated with drawings that remind us of Korean period dramas (Takane 2006, Image 9). Among the many fortune-telling services and products available are some that might be described as humorous or amusing. One example is an online game called Korean Food Fortune-Telling. It figures out each individual’s personality type and predicts their fortune based on an assessment of which Korean dish correlates with his or her birthday, blood type, and Chinese zodiac sign. [5]

Image 10. Fortune Telling Street, an Underground Passage near Xingtian Temple in Taipei, Taiwan, 2006. Photo by Ellery. Wikimedia Commons.

Many Japanese tour companies sponsor or promote fortune-telling tours to Hong Kong, Shanghai and Taipei that come complete with translators and guides. Because several traditional types of fortune-telling have Chinese origins, these tours are pitched as a chance to access more “authentic” versions of fortune-telling than those which are available in Japan. Japanese tourists throng to the famous underground passage known as Fortune Telling Street, located near Xingtian Temple in Taipei (Image 10). When I visited, I noticed many stalls featuring signs marked, “Nihongo OK” ( “Japanese okay.”) Upon overhearing brief interactions with Japanese clients, however, I received the impression that their Japanese language competence was not particularly advanced.

One fortune-telling entrepreneur in Taipei who has been especially successful in appealing to the Japanese girl market is Ryūha (real name: Watanabe Hiromi.) Born in Japan and a graduate of Aoyama Gakuin University, she has lived in Taiwan since 1997 and oversees a few shops, including her flagship fortune-telling salon, Ryūha (Dragon Wing). Ryūha considers Taiwan to be a “top brand” for East Asian fortune-telling. She is often featured in travel segments on Japanese television as well as in other videos (see Watanabe 2013). She attained fame as a karizuma uranai-shi (“celebrity fortune teller”) via four books and numerous articles in Japanese women’s magazines which attracted fans to Taipei to consult with her. She has also created her own deck of oracle cards based on the classic Chinese fortune-telling text, the I Ching (Book of Changes, Watanabe 2015, Image 11).

Image 11. Taiwan Wave-Style Fortune-Telling Cards (Watanabe 2015).

Conclusion

Together with contemporary media forms, cross-border travel, immigration, and the internet, urban spaces and activities enable shared understandings among girls, creating a type of sub-stratum culture that is found throughout the region. This is a layer of culture that, at times, renders national boundaries irrelevant.

When girls in Taipei, Seoul, or Hong Kong enter purikura booths, they are not thinking in terms of nationality. Nor are they thinking in terms of the other types of political structure that typically constitute the central focus of transregional studies. As consumers of popular culture and the feminine, they are not passive recipients of whatever products or images are offered to them, instead displaying a degree of control in the ways that they use and modify them. They also produce their own cultural products. Beyond essentialist notions of cultural identity, they are forging a transnational female urbanism that is located below or above the level of nationality.

References

Abraham, Yamila. 2010. Boys’ love thrives in conservative Indonesia. Boys' Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-cultural Fandom of the Genre, Antonia Levi, Mark McHarry, and Dru Pagliassotti, eds, 44-45. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

Bardsley, Jan. 2011. “The maiko boom: The revival of Kyoto’s novice geisha.” Japanese Studies Review 15: 35-60.

Cosplay Make. 2016. Twitter post, 12 September. Online at https://twitter.com/COSPLAY_MAKE Accessed 25 July, 2017.

Enloe, Cynthia. 2004. The Curious Feminist: Searching for Women in a New Age of Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fukuoka Prefectural Government 2010. Asian Beat Multilingual Pop Culture Website. Asia Youth Culture Center. Online at http://asianbeat.com/en/. Accessed 25 July, 2017.

Jiwani, Yasmin, Candis Steenbergen, and Claudia Mitchell. 2006. Girlhood: Redefining the Limits. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Kang, Dredge Byung’chu. 2017. “Eastern orientations: Thai middle-class gay desire for ‘white Asians.’” Culture, Theory and Critique 58 (2): 1-208.

Kim, Jae-heun. 2017. “China’s ban shifting hallyu to Southeast Asia.” The Korea Times 02 February. Online at http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2017/02/688_223171.html Accessed 25 July, 2017.

Li, Yannan. 2009. Japanese Boy-Love Manga and the Global Fandom: A Case Study of Chinese Female Readers. MA Thesis, Department of Communication, Indiana University-Purdue.

Martin, Fran. 2012. “Girls who love boys’ love: Japanese homoerotic manga as trans-national Taiwan culture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13 (3): 365-383.

McLelland, Mark J., Kazumi Nagaike, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker, eds. 2015. Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. Miller, Laura. 2003. “Graffiti photos: Expressive art in Japanese girls’ culture.” Harvard Asia Quarterly 7 (3): 31-42.

Miller, Laura. 2005. “Bad girl photography.” In Bad Girls of Japan, edited by Laura Miller and Jan Bardsley, 127-141. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Miller, Laura. 2008. “Extreme Makeover for a Heian-Era Wizard.” Mechademia: An Annual Forum for Anime, Manga and the Fan Arts. Issue #3: Limits of the Human, 30-45. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Miller, Laura. 2006. Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Miller, Laura. 2011a. “Cute masquerade and the pimping of Japan.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 20 (1): 18–29.

Miller, Laura. 2011b. “Tantalizing tarot and cute cartomancy in Japan.” Japanese Studies 31 (1): 73-91.

Miller, Laura. 2014.“The divination arts in girl culture.” In Capturing Contemporary Japan: Differentiation and Uncertainty, edited by Satsuki Kawano, Glenda S. Roberts, and Susan Long, 334-358. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Miller, Laura. 2016. “Scholar girl meets manga maniac, media specialist, and cultural gatekeeper.” In The End of Cool Japan: Ethical, Legal, and Cultural Challenges to Japanese Popular Culture, edited by Mark McLelland, 51-69. New York: Routledge.

Miller, Laura. 2017. “Japanese tarot cards” ASIA Network Exchange: A Journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Art 24 (1): 1-28.

Mizohata, Sachie. 2016. “Nippon Kaigi: Empire, contradiction, and Japan’s future.” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 14 (21). Online at http://apjjf.org/2016/21/Mizohata.html Accessed 31 July, 2017.

Nye, Joseph. 1990. “Soft power.” Foreign Policy 80: 153-171.

Nakamura, Tamio. 2008. “A proposed Draft Charter for an East Asian Community: Illustrative Comparisons with the European Experience.” Social Science Japan 38, March.

Rastati, Ranny. 2015. “Dari soft power Jepang hingga Hijab Cosplay” (Cosplay from Japanese soft power to cosplay hijab). Jurnal Masyarakat dan Budaya LIPI 17 (3):371-388.

Smith, Michael Peter. 2005. “Power in place/places of power: Contextualizing transnational research.” City & Society, 17 (1): 5-34.

Takahara, Eiri. 2006. “The Consciousness of the Girl.” In Woman Critiqued: Translated Essays on Japanese Women’s Writing, ed. Rebecca Copeland, 185-198. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Takahisa, Zeze. 2003. Moon Child. Feature film. Tokyo: Shōchiku Eiga.

Takane, Kokumon. 2006. Kokumon no kanryū uranai (Kokumon’s Korean Wave Fortune-telling). Tokyo: Tōhō Shuppan.

Takita, Yōjirō, director. 2001. Onmyōji (The Yin Yang Master). Feature film. Tokyo: Tōhō Studios.

Tsukagoshi, Kenji. 2003. MOON CHILD―HYDE & Gackt. Photographic book. Tokyo: Wani Books Co., Ltd.

Wang, Amber. 2007. “Japanese ‘cosplay’ draws huge following in Taiwan.” Things Asian, 13 November. Online at http://thingsasian.com/story/japanese-cosplay-draws-huge-following-taiwan Accessed 26 July, 2017.

Watanabe, Ryūha. 2013. Taiwan no uranai-shi (Fortune tellers of Taiwan). You Tube clip from Kansai TV. Online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4K_2MMRZos. Accessed 26 July, 2017.

Watanabe, Ryūha 2015. Taiwan-ryū Ryūha ekisen kādo (Ryūha’s Taiwan Wave I Ching Fortune-Telling Cards). Taipei: Ryūha Kokusai Bunka Ltd.

Yanagi, Watei. 2005. Onna o ageru! Hanryū ‘kao uranai’ (Just for women! Korean Wave-style face-reading). Tokyo: Goma Books.

Laura Miller is the Ei’ichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. She has published more than 70 articles and book chapters on Japanese culture and language. She is the author of Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics (University of California, 2006), and co-editor of three other books.

[1] Anecdotes concerning the denigration of girl culture research can be found in Miller (2016).

[2] There was a brief easing in the intensity of promotional efforts associated with the image of Cool Japan after the triple disaster (earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown) faced by the nation in 2011. For a few years, this concept was supplanted with a new soft power keyword, kizuna, a term often translated as “bonds.”

[3] I discuss some transnational forms of beauty treatment, such as the Korean salt scrubs found in Japanese aesthetic salons, as well as Japanese beauty tourism to Korea (Miller 2006).

[4] The Sega website for Taiwan can be accessed at http://purikura.segataiwan.com.tw/. Accessed on 26 July, 2017.

[5]Kankoku fūdo uranai (Korean Food Fortune-telling) can be found online at http://www.k-plaza.com/life/life_uranaitop.html. Accessed on 29 July, 2017.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.