Abstract

In this second of two articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. In these two essays, I provide a descriptive overview of the considerable data derived from this 178-question survey, noting trends and themes that emerge therein, in order to provide a broad orientation before narrowing my scope in subsequent analyses. In Part 2, I explore the remaining survey responses related to the following research questions: (1) How does pathshala help students/teachers navigate their social roles and identities?; (2) How does pathshala help students/teachers deal with tensions between Jainism and modernity?; (3) What is the content of pathshala?, and (4) How influential is pathshala for U.S. Jains?

Key words: Jainism, pathshala, Jain education, pedagogy, Jain diaspora, minority, Jains in the United States, intermarriage, pluralism, future of Jainism, second- and third-generation Jains, Young Jains of America, Jain orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy, Jainism and science, Jain social engagement

Introduction

In this paper, the second of two related articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. In these two essays, I provide a descriptive overview of the considerable data derived from this 178-question survey (Appendix A), noting trends and themes that emerge therein, in order to provide a broad orientation before narrowing my scope in subsequent analyses. In Part 1, I described the history of Jainism and its community of mendicants and lay householders, the role of pathshala in the context of Jain immigration, along with the survey’s methodology and demographics. I explored survey respondents’ views on the goals of pathshala, how the uniform JAINA pathshala curriculum functions as “text,” as well as heightened levels of authority ascribed to teachers, family members, and self-motivated learning.

In Part 2, I explore how pathshala provides multicultural strategies to help Jain students and teachers navigate their identity as Jains in non-Jain diaspora contexts through four remaining research questions: (1) How does pathshala help students/teachers navigate their social roles and identities? (2) How does pathshala help students/teachers deal with tensions between Jainism and modernity?; (3) What is the content of pathshala?, and (4) How influential is pathshala for U.S. Jains? This analysis unfolds through three assertions.

First, following Prema Kurien’s analysis of Hindus in diaspora in her book A Place at the Multicultural Table (2007), I assert that pathshala provides “dual or mixed strategies” for minority Jains in the U.S. to navigate their own multicultural identity. Within a primarily non-Jain U.S. context, pathshala presents several such strategies, such as: (1) presenting Jainism as a universal “Way of Life” for Jains and non-Jains; (2) enabling Jains to flexibly express their values in non-Jain environments; and (3) transmitting Jain-specific practices of diet, fasting, and other rituals while also assisting Jains in creating relationships with other Jains nationwide, and informing marital choices and offspring participation. Second, pathshala supports independent thought in evaluating the truths of Jainism and modern society, and also supports interreligious acceptance. However, pathshala classes are not a significant source for exploring the content of conflicting truth claims, whether between Jainism and science, politics, and culture, or between Jainism and other religious traditions. Students and teachers rely largely on self-learning, social networks, and other personal relations to explore the content of these competing claims. Third, students and teachers are invested in the future development of pathshala, offering suggestions for strengthening classes, including future topics for discussion—such as intermarriage and alcohol use, among others—as well as desired future activities such as community service, learning Jain rituals, yoga, and meditation. Teachers had a strong desire to recruit future instructors, and over one-third of students expressed interest in teaching in the future. At present, a gap in pathshala education exists after high school in which future pathshala programming or online pathshala classes may help keep young Jains connected during transitions into professional life.

Pathshala Provides Minority Jains with Strategies for Navigating Multicultural Identity

U.S. pathshala classes began in the 1980s, often being held in private homes, to serve the growing number of Jains entering the country through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Williams 2000, 213). The act established a prioritized professional skills and family reunification, precipitating a flow of highly trained South Asian professionals, of which Jains were well-suited due to their historic merchant-caste roots in certain “nonviolent” occupations, such as engineering, medicine, and banking (213).[1] Like many South Asian communities recreating versions of “homeland” through socio-economic, political, and cultural institutions (Rai and Reeves 2009, 3), Jains financed and constructed regional temples as their numbers grew, creating brick and mortar centers where many community activities, including pathshala, could be held. As detailed in Part 1, the Federation of Jains in North America (JAINA) formed an Education Committee in 1992 to design a formal pathshala curriculum. This work continues to the present day with the production of eleven JAINA Education Series Pathshala (JES) “blue books” and six additional reference books, all available at very low cost to temples or as free online downloads at the Jain E-library.

Jainism Is a Minority Tradition Unfamiliar to Most Non-Jains

Pathshala exemplifies a “will to survive as a minority by transmitting a heritage” to second- and third-generation Jains in a non-Jain context in which few are familiar with the tradition’s intellectual or ethical commitments (Chaliand and Rageau 1995: xiv-xviii). Indeed, the majority of pathshala students and teachers who participated in the survey had very few Jain peers or colleagues in their work or school environments. Most students reported no Jain peers (23%, n=26) or proportions less than five percent (65%), while teachers similarly had either no Jain colleagues (45%, n=44) or the proportions were smaller than five percent (39%).

As in India, where Jains make up less than one percent of the population, Jains are a small minority in the United States. Because the U.S. Census does not provide “Jainism” as a religious identity option, the Jain population is even more difficult to track. A 2012 Pew Research Center report calculated that Jains accounted for two percent of the Indian-American population, which was just under 3.5 million according to 2016 census estimates, resulting in a U.S. Jain population of approximately 70,000. JAINA claims to represent 150,000 Jains in North America. Many estimates place the U.S. population of Jains between these two figures, near 100,000.

Given the low number of Jain peers, most Jains have very diverse social groups, comprised of people from multiple philosophical and religious traditions. Student respondents described their peer groups as being composed of individuals who identified as Hindu, Protestant Christian, Catholic, Muslim, and Atheist. Teachers’ peers were largely Hindu, Christian, Catholic, Muslim, Sikh, and Jewish. About a third of students (S) and teachers (T) reported having described themselves as a follower of a more recognizable Indian tradition, such as Hinduism or Buddhism, for the sake of ease (S 38%, n=26; T 27%, n=44), and a small minority described themselves as atheist for the sake of ease (S 12%; T 5%), suggesting that many Jains encounter peers unacquainted with their tradition.

In an article written for the YJA Young Minds online platform titled “Jain or Hindu? Finding a Distinct Religious Identity in a Multi-Faith Society,” Nikhil Bumb describes being presented a Religious Identification Form on the first day of college on which “Jainism” was not listed as an option, leaving him to choose between “Hinduism” or “Other.” Reflecting on his dual Jain-Hindu religious identity, Bumb writes:

On that first day of college, while I was disappointed at not seeing Jainism on the form, my dual religious identity was not completely out of place and, as I later discovered, [was] a common confusion for young first generation Jain Americans. I grew up learning both the Jain faith and Hindu culture — I attended a Hindu Sunday school for 13 years, I was (and still am) fascinated by Hindu mythology, and my family celebrates both Hindu and Jain festivals at our local joint Hindu-Jain temple. Yet it was always clear to my sisters and me that our religion was Jainism, not Hinduism or even both. (2010)

Perhaps due to this lack of local and national familiarity with Jain identity, a portion of respondents had experienced being teased or made fun of for their Jain beliefs or practices either rarely (S 50%, n=26; T 30%, n=44) or frequently (S 4%; T 5%), although very few reported being aggressively bullied for their Jain beliefs or practices either rarely (S 8%; T 9%) or frequently (T 2%). A meaningful minority of students found it “challenging to stay a Jain and be part of my peer community” (S 23%, n=26; T 7%, n=44), while a similar minority of teachers agreed that “Sometimes I feel that being a Jain makes me not fit in with my peers” (S 8%, n=26; T 18%, n=44). Likewise, participants were asked if their “Jain beliefs ever led to a clash with a friend or colleague of another religious or philosophical tradition or perspective,” to which some students and teachers responded affirmatively (S 42%, n=26; T 18%, n=44). When asked to describe the “biggest challenge/s that you encounter in being a Jain among your friends or in your work/school environment,” students and teachers described points of disconnect that were primarily focused on diet-related issues (which I will return to shortly), such as vegetarianism, veganism and/or not eating root vegetables, as well as other visible practices of non-harm that are dissonant with the surrounding culture (Table 2.1).

|

Students[2]

|

Teachers

|

Table 2.1 Question: “What is/are the biggest challenge/s that you encounter in being a Jain among your friends or in your work/school environment?” Note: When a specific term was repeated verbatim by respondents, I have listed that term once, and included (2) to indicate its double use.

Within these challenges, many participants described needing to explain a belief, attitude, or practice of Jainism to peers unfamiliar with the community, or “deal with” normative practices of the majority, ranging from meat eating to riding horses, killing insects, using alcohol, and participating in potlucks and business lunches, among others. In the face of these challenges, most respondents felt that pathshala helped them navigate these hurdles in two primary ways. First, it helped Jains to explain their minority tradition in more universal terms to non-Jains, and second, it facilitated the growth of Jain-specific activities and social connections.

Pathshala Strategy 1: Presenting Jainism as a Universal “Way of Life” for Jains and Non-Jains

In her book A Place at the Multicultural Table (2007), Prema Kurien describes the shift of American Hinduism from multiple expressions of “popular Hinduism” that characterize life in India, to a more streamlined and universal “official Hinduism” that can be recognized in the terms of American pluralism (2007). In this context, Kurien explores how Hindu youth organizations help students navigate ethnic identity through “dual or mixed strategies” that may initially appear contradictory, such as heritage pride and preservation, selective acculturation, or reactivity to ethnic segregation or victimization, among other responses (2007, 213-215).

Jain pathshala sits at a similar juncture, perpetuating a more universal image of Jainism while also providing specific tools and strategies for preserving Jain identity in a multicultural context. In an op-ed for the The South Asian Times titled “Pathshala: The Next Generation of American Jains,” JAINA Education Committee Chair Pravin Shah explains that U.S. pathshala curriculum is “primarily based on American culture,” and “aims to teach our kids based on [the] current environment, the message of compassion and nonviolence in all aspects of life” (2017a). Without access to the popular forms of Jainism that one would find in India based on regional languages, sect-specific temples, mendicant guides, and family rituals, diaspora Jainism is condensed in pathshala teaching materials that utilize common cultural terms, stories, and universal themes for Jains in a North American context.[3] Although pathshala blue books retain a connection to the history of mendicant renunciation practices and provide a basic overview of sect differences, they primarily emphasize non-sectarian and universal tools for a “Jain Way of Life,” a path Sabine Scholz describes as the “re-use and reinterpretation” of ancient Jain concepts in modern arenas of consumerism, vegetarianism, environmental concern, and charity available to Jains and non-Jains alike (2012). Likewise, in his book Jain Way of Life, U.S.-based author Yogendra Jain focuses on the three principles of nonviolence [ahiṃsā], non-attachment to goods [aparigraha], and non-one-sided view [anekāntavāda] that are “ideal for Jains and Non-Jains . . . an easy to understand guide for blending Jain practices with a North American lifestyle” (2007).

Marcus Banks describes this universal approach as a “neo-orthodox” tendency among diaspora Jains to recast the “orthodox” mendicant path of renunciation as a universal mode of personal and social improvement removed from its sectarian ascetic roots (1991, 252-257). In addition to scholars who have further developed the “neo-orthodox” paradigm (Vallely 2008, Shah 2014), an institutional example of universalization can also be found in the global spread of Prekṣā Dhyāna, a form of meditational and postural yoga created by Terapanthī monk Mahāprajña in the 1970s (Jain 2016, 236-237). As described in Part 1, Prekṣā Dhyāna is now disseminated globally to Jains and non-Jains by a special class of intermediate mendicant known as samaṇ (male) and samaṇī (female) who received special dispensation to travel in 1980. The Prekṣā Dhyāna centers offer classes and events to help address modern conflicts within society at the personal, national, and global level (236).

Consequently, a picture emerges of U.S. Jains whose identity involves, to a considerable degree, introducing others to and educating them about the Jain tradition and the relevance of its ideals and practices in a non-Jain context. Unlike in India, where Jainism is part of the historical and cultural landscape, U.S. Jains cannot assume that the wider society is familiar with Jainism. Yet, most respondents felt it was very important (vi) or moderately important (mi) for their peers and colleagues to know that they were Jain (S vi 23%, mi 46%, n=26; T vi 36%, mi 32%, n=44).

The vast majority of students (85%, n=26) and teachers (91%, n=44) agreed that “Attending pathshala makes it easier for me to explain my Jain identity to others.” This is a noteworthy point, considering the related survey statement: “I find it difficult to explain to my friends what it means to be a Jain.” Among the choices provided, a significant number of participants selected “I do not find it difficult to discuss Jainism with others” (S 35%, n=26; T 55%, n=44), while an equally significant percentage selected “I find it difficult, but I try to explain basic Jain beliefs the best I can,” (S 42%; T 30%). Those who attempt to explain in spite of the difficulty far outweigh those who try to avoid the topic because of the difficulty (S 4%; T 0%), suggesting that U.S. Jains desire for peers and colleagues to know them in relation to their tradition even when it is challenging to do so, a commitment that pathshala appears to support.

A significant minority of students and teachers also affirmed that they had encouraged their friends to adopt Jain beliefs or practices (S 38%, n=26; T 34%, n=44), though most stated that they did so because they believed the practices were correct, and not necessarily because the practices were Jain (S 58%, n=26; T 41%, n=44). In keeping with trends toward multicultural universality rather than Jain-specific creeds, no respondents asked friends to consider “becoming Jain.”[4]

Pathshala classes (and temple complexes generally) also provide a unique “Jain” location to introduce non-Jains to the Jain tradition and community within multicultural society. Teachers reported bringing non-Jain friends to pathshala and temple more frequently than students did. Regarding pathshala, the frequency with which respondents reported bringing non-Jain friends was as follows: never (S 50%, n=26; T 25%, n=44), one time (S 42%; T 30%), two to three times (S 8%; T 30%), or four or more occasions (T 16%). Regarding the temple, respondents reported bringing non-Jain friends: never (S 42%, n=26; T 18%, n=44), one time (S 38%; T 18%), two to three times (S 15%; T 41%), or on four or more occasions (S 4%; T 23%). The majority of students and teachers were interested in having a special day to invite non-Jain friends to pathshala (S 77%, n=26; T 68%, n=44) or to the temple (S 88%; T 66%).

Pathshala Strategy 2: Enabling Jains to Express Jain Values Flexibly in Non-Jain Contexts

Although “neo-orthodox” trends in Jainism often stress the universal quality of Jain values, the U.S. pathshala curriculum transmits a great deal of Jain-specific teachings. As described in Part 1, the JAINA Education Series (JES) blue books, function as the primary “text” for transmitting Jain beliefs and practices in temple education that is used by the vast majority of national pathshalas and survey respondents (88%; n=69).

Created by lay Jains beginning in 1992, the JAINA curriculum condenses Jain mendicant texts, lay manuals, philosophical concepts, karma theory, universal history, vocabulary, stutis, rituals, and ethical application, additionally including interactive activities and discussion topics. While only rarely referencing canonical or ancient Jain texts, the blue books answer the great questions of existence through a Jain lens, such as “What exists…?,” “How do we know?,” and “How do we act?,” modulated for different learning levels.

For example, the first-level Jain Moral Skits (JES 104) teaches students implicit practices of non-harm (ahiṃsā) toward creatures small and large—from insects to one’s teacher—through interactive dialogs related to respect (64-66). The second-level Jain Story Book (JES 203) develops the earlier lessons by offering a basic framework of Jain knowledge, such as the meaning of ahiṃsā, karma, and the Jain classification of living and nonliving beings according to their possession of one through five senses, each with a unique “soul” (ātmān or jīva) that desires to live. While these concepts derive from various texts and commentaries dating from antiquity through the medieval period (especially the Tāttvārtha-sūtra of Umāsvāti [2nd-5th century CE] that are considered authoritative by Digambara and Śvetāmbara Jains), the JAINA Education Committee does not explicitly reference these technical sources, instead repackaging the content for younger readers in a more personal narrative form.

The higher-level books—such as Jain Philosophy and Practice 1 and 2 (JES 301, 401)—introduce Prākrit and Sanskrit terminology, offer greater enumerations of Jain history, the distinct roles of mendicants and lay people, sect-specific practices, the ethical vows of Jainism, the account of life forms, various kinds of karma, and the role of mental and physical restraints in uprooting violent attitudes and actions that harm oneself and others. These detailed categories of Jain philosophy and ethics are usually tested with quizzes as part of pathshala education.

The majority of pathshala students and teachers described themselves as “very dedicated to Jain beliefs” (S 58%, n=26; T 68%, n=44) or “somewhat dedicated to Jain beliefs” (S 35%; T 32%). The vast majority accepted the Jain concept of the jīva/ātman (or soul) (S 81%, n=26; T 91%, n=44) as well as that of karma (S 88%; T 89%). When asked, “To what extent do you believe in the Jain worldview, philosophy, scriptures and practices as an integrated whole?,” most respondents reported the “highest extent” (S 35%, n=26; T 57%, n=44) or a “high extent” (S 27%; T 27%), with the remaining participants choosing “neither high nor low” (S 19%; T 7%), the “lowest extent” (S 4%), “I don't know” (S 4%; T 2%), or “I have not thought about this before” (S 4%; T 7%).

Beyond imparting a conceptual understanding of Jainism, pathshala assists participants in flexibly applying these lessons within the context of their personal and social lives, although it does not provide prescriptive rules on how to do so. Given the non-Jain contexts that most Jains inhabit, it is understandable that a significant minority of respondents agreed with the statement, “I feel that my work/school life and my life as a Jain are frequently separate” (S 31%, n=26; T 30%, n=44). At the same time, a greater portion affirmed that “Pathshala helps me hold my work/school life and my life as a Jain together” (S 65%, n=26; T 77%, n=44). Relatedly, a number of participants agreed that they “experience problems or questions in [their] personal or professional life that are not addressed by the pathshala curriculum” (S 58%, n=26; T 45%, n=44). Yet, those respondents’ who left additional comments remarked that pathshala provides a grounding in general concepts rather than specific advice. One comment reads: “Ahimsa may be a virtue to cultivate so you can solve your professional life problems, but you need to choose to introspect on it.” Another asserts: “Pathshala is not meant to impart professional education or resolve personal problems. Pathshala education gives one a stability and backbone [for] one’s personal/professional life.”

Bindi Shah explores the flexible application of Jain ideals in her recent analysis of second-generation Jains in Britain and the U.S. (2014). Shah asserts that “neo-orthodox Jainism gives young Jains flexibility to interpret the Jain religious tradition and actively construct their own Jain biography” (2014, 519). Shah describes a “cataphatic reflexivity,”[5] wherein Jains construct their identity as Jains by rationally integrating individually chosen ideals into their personal and professional habits, environments, and relations (521). Pathshala may play a significant role in this reflexivity, according to survey responses.

Consider, for example, that all students (100%, n=22) and the vast majority of teachers (95%, n=42) answered affirmatively when asked, “Does Pathshala help you to understand how you might apply the five basic Jain principles (nonviolence, truth telling, non-stealing, sexual restraint, non-attachment to goods) in your social life (work, school, etc.)?” The majority of respondents also agreed that pathshala helps them understand how to “apply ahimsa to challenges at school or work” (S 85%, n=22; T 84%, n=42) and how to “apply ahimsa to challenges in family or close personal relationships” (S 81%; T 73%).

Further, participants felt that pathshala motivated diverse forms of positive action within their social settings. When asked, “Do you feel that Jain beliefs and practices help you to stand up for what you think is right even when others disagree?,” the vast majority responded affirmatively (S 91%, n=22; T 86%, n=42). Most also agreed that: “My commitment to Jain beliefs and practices enables me to make unique contributions in school or work” (S 77%, n=26; T 80%, n=44). Likewise, the majority concurred when asked: “Do you feel that being a Jain gives you any advantages or insights in your school or work life?” (S 81%, n=26; T 57%, n=44) as well as when asked: “Do you feel that Jain beliefs and practice inspire you to imagine new solutions or innovations in your world or life to curb violence?” (S 82%, n=22; T 83%, n=42).

On the flip side, where ethical “rules” do exist—whether from family or community practices or from historical texts describing correct conduct for Jain lay people (śrāvaka-acāra)—students and teachers do not always adhere to them. For example, most participants confirmed discussing the following prohibitions of ahiṃsā within pathshala: buying cars with leather interiors (derived from animals) (S 69%, n=26; T 66%, n=44); buying leather shoes (S 77%; T 61%); buying leather bags, purses, or belts (S 81%; T 66%); wearing silk (derived from boiling silk worms) (S 65%; T 77%); wearing fur derived from animals (S 73%; T 77%); buying products tested on animals (S 88%; T 80%); and buying products containing varakh (the silver foil on Indian sweets made from animal byproducts (S 77%; T 70%). Yet, when asked if they had purchased any of the products listed above after discussing these particular prohibitions in pathshala class, two-thirds of students (65%), and one-third of teachers (36%) responded that they had done so.

Whether in relation to positive practices or specific prohibitions, pathshala does not appear to produce rule-based adherence so much as it leads teachers and students to seek to independently and flexibly activate their Jain identity and ideals within non-Jain contexts.

Strategy 3: Pathshala Transmits Jain-Specific Practices of Diet, Fasting, and Ritual, and Influences Nationwide Networks, Marital Choice, and Offspring Participation

In addition to helping students and teachers explain and maintain their identity among non-Jains, pathshala nurtures specific cultural practices that strengthen Jain identity within the local, national, and global Jain community.

Diet

One of the most visible core practices for diaspora Jains is adherence to vegetarianism. While some historians argue that early Jain mendicants may have allowed the consumption of meat on certain occasions, such as in the case of meat provided as alms to an ascetic when the animal had not been killed specifically for that purpose, or when a lay person was sick, or during famine (Dundas 2002, 177; Alsdorf 2010/1962, 6-16), lay Jains have continually disputed these arguments (Kapadia 2010/1933). What is absolutely clear is that consuming food of any kind is an inescapable instinct that generates karmic cost in the Jain account of biological and ethical existence (Jaini 2010a, 284-289). Since animals, like humans, are considered five-sensed organisms in the Jain taxonomy of living beings, killing them for any reason attracts the worst karmic costs (Vallely 2018, 6-13). Mendicant manuals prescribe very strict rules for consuming food. According to these rules, for example, only one meal should be consumed per day and it should be comprised of single-sensed life forms (primarily plants and pulses) prepared by lay people. In addition, common foods such a garlic, root vegetables, alcohol, and honey should be avoided, as their consumption involves the destruction of innumerable beings in the plant itself, in the ground, or during the processes of fermentation and harvesting. Lay Jains in diaspora, however, often emphasize the compassionate aspect of not eating animals rather than the karmic cost of eating anything at all (Vallely 2008, 566-570). James Laidlaw summarizes the diaspora approach succinctly, claiming that “. . . as it is presented for external consumption, Jainism is more or less a campaign for vegetarianism” (1995, 99). Moreover, one of the explicit goals of American pathshala, as stated by Pravin Shah (and evident in many of the lower-level blue books), is to “encourage vegetarianism and [a] vegan way of life” (2017a).

It is little surprise, then, that pathshala respondents practiced a vegetarian diet of some kind, with the majority being lacto vegetarian (consuming dairy products, but no meat or eggs) (S 73%, n=26; T 52%, n=44), with smaller percentages being ovo-lacto vegetarian (consuming eggs and dairy products, but no meat) (S 23%; T 9%), vegan (consuming no meat, dairy products, or eggs, and using no leather or fur) (S 4%; T 14%), or Jain vegetarian (consuming no meat, eggs, garlic, onion, or root vegetables) (T 20%).[6] No respondents selected pescatarian (consuming fish), or omnivore (consuming meat, dairy products, and vegetables).

Living a vegetarian “Jain Way of Life” within the U.S. context—where citizens have the second highest per capita meat consumption in the world (200/lb per person in 2013)—is not without difficulty (“Top Meat”). As mentioned above (Table 2.1), when asked to describe the “biggest challenge/s that you encounter in being a Jain among your friends or in your work/school environment,” those who offered open-end responses overwhelmingly referred to dietary issues (S 55%; n=11; T 75%; n=28). A significant minority of students (31%, n=26) had also experienced direct peer pressure to eat meat, primarily between the ages of 4-10 (27%), 10-14 (27%) and 15-18 (15%). A smaller portion of teachers had experienced pressure to eat meat (16%, n=44). primarily between the ages of 10-14 (11%) and 23-30 (11%).

Pathshala is a considerable source of support in relation to Jain dietary commitments. Most respondents agreed that they “learn about diet or food practices in pathshala” (S 86%, n=22; T 88%, n=42), and a majority deemed pathshala “an important source in maintaining my commitment to my dietary ethics” (S 62%, n=26; T 82%, n=44). Bindi Shah describes a pragmatic approach among young Jains, who flexibly interpret Jain food ethics depending on context; for instance, by avoiding root vegetables at home, but not when out with friends (2014, 519). Many young Jains also now advocate a vegan diet as a modern expression of ancient ideals of non-harm in light of the cruelties involved in industrial dairy production (Shah 2014, 519-521; Evans 2012) [7]. This flexible application of Jain food ethics cuts the other way as well, as a significant minority felt that one could be Jain while also eating meat (Yes S 19%, n=26; T 25%, n=44 / No S 65%; T 57% / I don’t know S 12%; T 11%).

Fasting

Most respondents reported that pathshala is a place where they learn about fasting (S 81%, n=26; T 80%, n=44). The practice of voluntary fasting derives directly from ancient Jain mendicant and lay texts that describe fasting as a means of restraining the senses and mind, enhancing subtle awareness, exploring one’s physical and psychological urges, and generating tolerance for discomfort of all kinds (Dundas 2002, 199-200). Nearly all participants had practiced some form of voluntary fasting during the eight to ten-day festivals of repentance known as Paryuṣaṇa and Daśa-lakṣaṇa-parvan (S 92%, n=26; T 93%, n=44), when there is considerable social support for fasts (Jaini 2001/1979, 209-217). Many had practiced fasting on their own outside these holiday periods as well (S 58%, n=26; T 68%, n=44). The majority of respondents who practiced fasting had attempted different kinds of fasts, such as refraining from: eating (S 92%, n=26; T 89%, n=44), or refraining from eating and drinking during certain times, such as before sun-up or after sun-down (S 85%; T 73%). Others had abstained from watching television (S 69%; T 30%), practiced veganism for a set duration (S 42%; T 36%), or refrained from activities such as making purchases (S 38%; T 32%), playing video games (S 38%; T 14%), using the telephone (S 35%; T 16%), gambling (S 23%; T 18%), or speaking (S 23%; T 25%). While pathshala was a significant source of learning about fasting, students listed other sources as well, such as parents (one participant specifically named “mom”)[8] (31%, n=16), grandparents (two respondents specifically named “grandmother”) (12%), family generally (8%), friends (4%), or the Jain Academic Bowl (4%). Teachers additionally described learning about fasting from parents (30%, n=35), family generally (25%), friends (14%), elders and community members (9%), grandparents (7%), JAINA books (5%), visiting Jain scholars (5%), Jain scriptures (5%), monks/nuns (2%), a guru (2%), and the internet (2%), indicating that the tradition of fasting is overwhelmingly transmitted orally.

Rituals

The role of ritual is changing among diaspora Jains. In Pravin Shah’s summary of American pathshala, he states that “Humanitarian services and environmental protection activities take priority over traditional [temple] rituals.” In relation to contexts in which rituals, such as sūtras, are taught, Shah claims that classes “emphasize the meaning of sutra[s] rather than blindly memorizing them” (2017a). Likewise, analyses of “neo-orthodox” diaspora trends are often characterized by anti-ritual attitudes (Banks 1991, 252-253, Shah 2014, 519).

Each of the JAINA curriculum blue books begins with common sūtra texts. Anecdotally, in the dozen pathshala classes that I have attended with students aged 14+ in Houston and Los Angeles, nearly all began with one of these sūtra recitations. Most survey respondents agreed that “Pathshala teaches me the meaning of specific Jain rituals” (S 86%, n=22; T 86%, n=42) and “how to perform specific Jain rituals” (S 64%, n=22; T 88%, n=42). As described in Part 1, and as a counterpoint to the perceived diminishment of rituals, the majority of respondents also answered positively when presented with the statement: “I have a desire to learn to do rituals (such as stutis, samayika, and pratikramana) in an Indian language in pathshala” (S 64%, n=22; T 57%, n=42). Similar majorities had a desire to learn the rituals in English (S 68%; T 65%), and to learn Jain devotional songs in an Indian language (S 72%, n=22; T 69%) even more so than in English (S 45%; T 48%). These answers suggest that pathshala does play a role in transmitting ritual, and could play a larger one in the future.

Creating National Jain Networks and Influencing Marital Choice and Offspring Participation

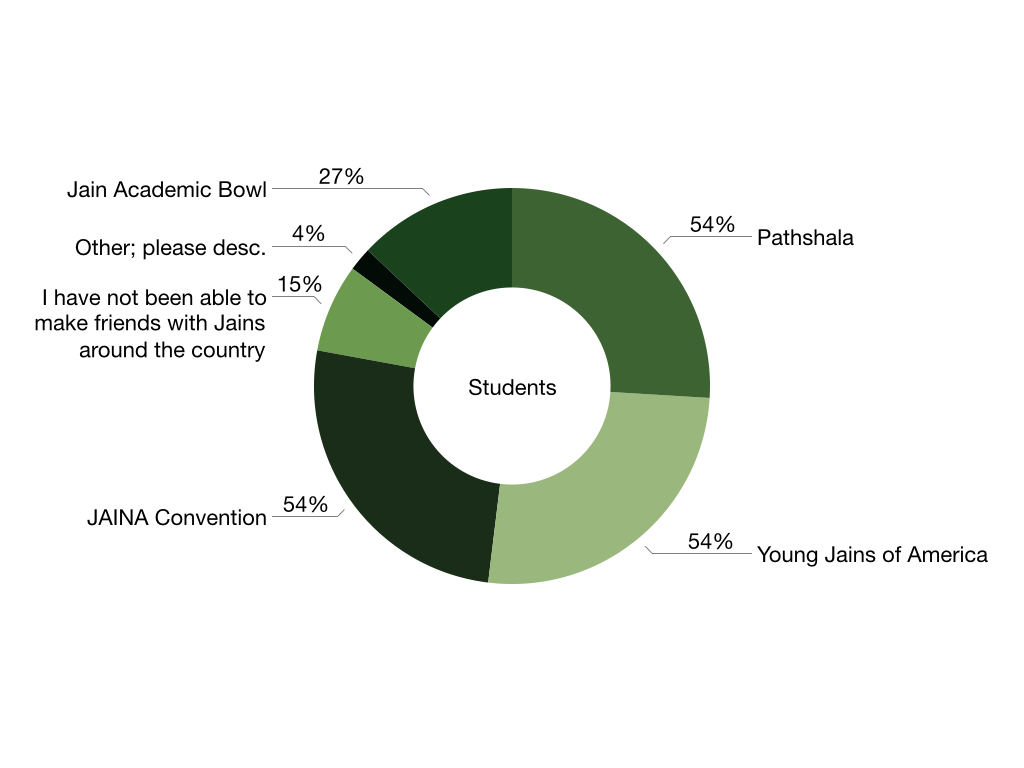

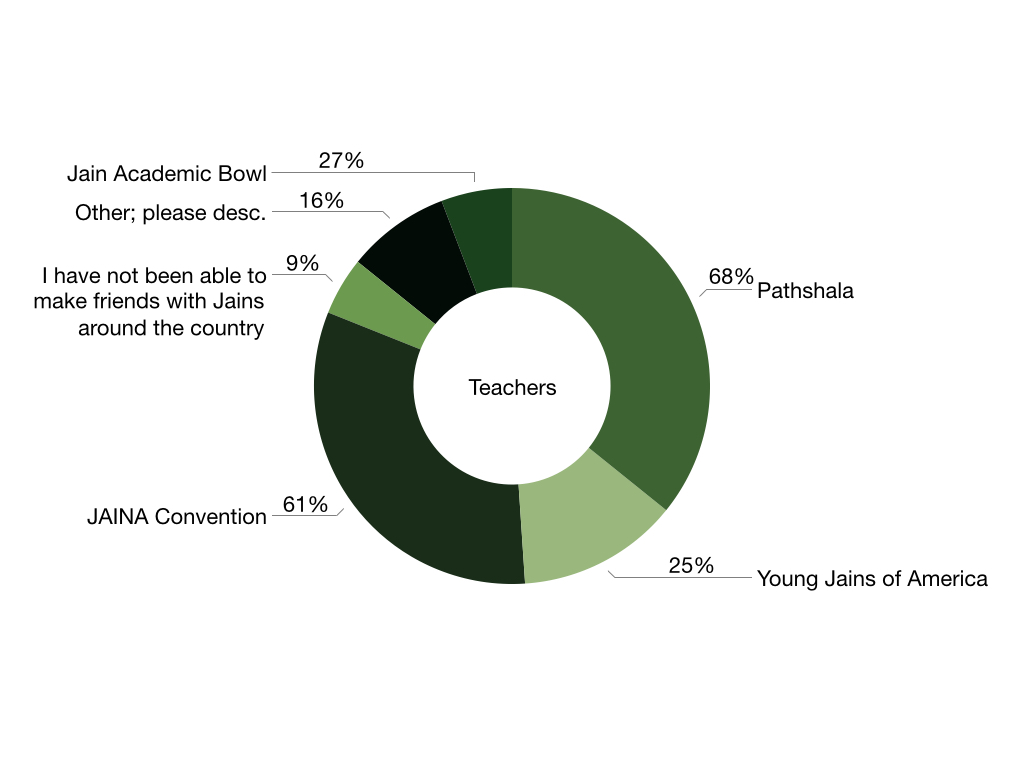

Perhaps more significant than any of these individual practices, pathshala supports Jain cultural identities by generating connections between U.S. Jains around the country, influencing marriage prospects for Jains, and building lasting future identification with the Jain community for individuals and their children. For example, the majority of respondents reported feeling “connected with Jains in different cities in the United States” (S 77%, n=26; T 82%, n=44). Pathshala ranked as the most significant source enabling that connection for teachers (68%, n=44), and tied as one of the three significant sources for students (54%, n=26) alongside JAINA conventions and Young Jains of America (Figures 2.1a and 2.1b).

Figure 2.1a Student responses to the question: “Which of the following have enabled you to make friends with Jains around the country? (Choose ALL that apply):” (n=26)

Figure 2.1b Teacher responses to the question: “Which of the following have enabled you to make friends with Jains around the country? (Choose ALL that apply):” (n=44)

Pathshala also influences marriage prospects among Jains. In Shah’s summary of U.S. pathshala, he reports that 70% of Jain children are marrying non-Jain Americans (2017a). Shah uses this statistic not to deter inter-marriage, but rather to encourage the appreciation of positive qualities of other religions and cultures whose adherents are coming into contact with Jainism as spouses and companions. Survey respondents were not explicitly asked about marrying another Jain, but whether pathshala had or would influence their choice of life partner. Among survey respondents who were already married, the majority of students (83%, n=6) and about half of teachers (44%, n=27) answered “yes” when asked: “Did the pathshala program have any impact on your choice for a life partner or spouse?” For single and/or unmarried participants, the majority of students and over half of teachers answered affirmatively when asked: “In the future, do you believe that the pathshala program may have any impact on your choice of a life partner or spouse?” (S 70%, n=20; T 52%, n=25).

While a subset of participants had “considered joining a different religious tradition or philosophical perspective (such as atheist or agnostic)” (S 14%, n=22; T 10%, n=42) or simply considered “leaving the Jain tradition” (S 14%; T 7%), the vast majority believed they would remain a Jain over the next ten years (S 86%, n=22; T 100%, n=42), as well as over the next twenty-five years (S 86%; T 100%). Beyond retaining their own connection to the tradition, most respondents felt they would have their children attend pathshala. When asked: “If you decide to have or adopt children, would you have them participate in pathshala?,” the strong majority answered positively (S 82%, n=22; T 90%, n=42), suggesting that attending pathshala may build intra-generational and inter-generational commitment to the Jain tradition and community into the future.

Pathshala Encourages Independent Thought, but Does Not Analyze the Content of Conflicting Truth Claims

Alongside these complex strategies for navigating Jain identity in non-Jain contexts, it is less clear how pathshala helps participants navigate intellectual or ethical tensions between truth claims of the Jain tradition when they clash with those of modern society.

Jains Accept Contradictions Between Their Tradition and Society, but Pathshala Is Not a Major Source of Guidance When Dealing with Such Conflict

A characteristic of neo-orthodox Jainism is the accommodation of rationalism, science, and humanist institutions in the West (Banks 1991, 252-253; Donaldson 2019), expressed in what one scholar calls the “scientization and academization” of Jainism (Auckland 2016). Similarly, Shah asserts that, in American pathshala, “No magic, blind faith, and super power help from heavenly gods (Devs) and goddesses (Devis) by reciting mantras are accepted and hence self-efforts and self-initiatives are valued” (2017a).

The majority of students (70%, n=26) and teachers (55%, n=44) agreed that “There are some beliefs of the Jain tradition that are at odds with modern culture, science, or politics.” One-third of students (35%, n=26) described areas of conflict as including vegetarianism, the concept of heavens and hells in Jainism,[9] the presence of life in earth-, air-, fire[-bodies], etc. which, according to one respondent’s comment “cannot be proven through science,” and the injuring of animals in dissection and/or animal testing. Teachers (50%, n=44) also described certain sources of conflict, including economic materialism and success, the Jain universe, non-possessiveness as “the opposite of what most pop culture teaches,” evolutionary theory, the Jain diet and vegetarianism, the Jain claim that the universe has no beginning or end, the claims of other religions regarding divine creation, cultural norms of hunting and fishing, karma and soul in relation to science, the Jain cycle of time versus linear time, and Jain sacred geography.

Relatedly, when presented with the question, “What, if any, contradictions within the Jain tradition would you like to explore further?,” respondents offered open-ended topics that point toward conflicting truth claims, including (S, n=10; T, n=21) (Table 2.2):

|

Students

|

Teachers

|

Table 2.2 “What, if any, contradictions within the Jain tradition would you like to explore further?” Note: Though some topics are repeated by respondents, I have listed them only once here, followed by (2), (3), etc. if that comment was listed more than one time.

Importantly, when respondents were asked how they address such conflicts or contradictions, parents and self-motivated investigation were cited more frequently as sources for reflection than pathshala teachers, pathshala class, or the curriculum blue books. In response to the statement: “When I encounter a claim or idea in school or work, or from science or society that is at odds with Jain belief and practices (Choose top three),” students responded: “I discuss it with my parents” (58%, n=26); “I reason it out in my own mind” (58%); “I explore the issue privately through the internet” (38%); “I discuss is with members of my Young Jains of America community” (31%); “I discuss it with my pathshala teacher/s” (27%); “I discuss it with my sibling/s” (27%); “I discuss it with my pathshala class” (23%); “I usually ignore such tensions” (19%); “I try to explore the issue through Jain Education Series blue books” (12%); or “I read specific sūtras or scriptural texts” (4%). Teachers also reasoned the issue out in their mind (61%, n=44), consulted parents (59%), utilized the internet (39%), discussed with sibling/s (30%), pathshala teachers (23%) or in pathshala class (23%). While pathshala teachers were considerable sources of authority when it came to Jain-related questions, as described in Part 1 of this analysis, they do not retain the same degree of authority when addressing conflicts between the truth claims of Jainism and those of society,

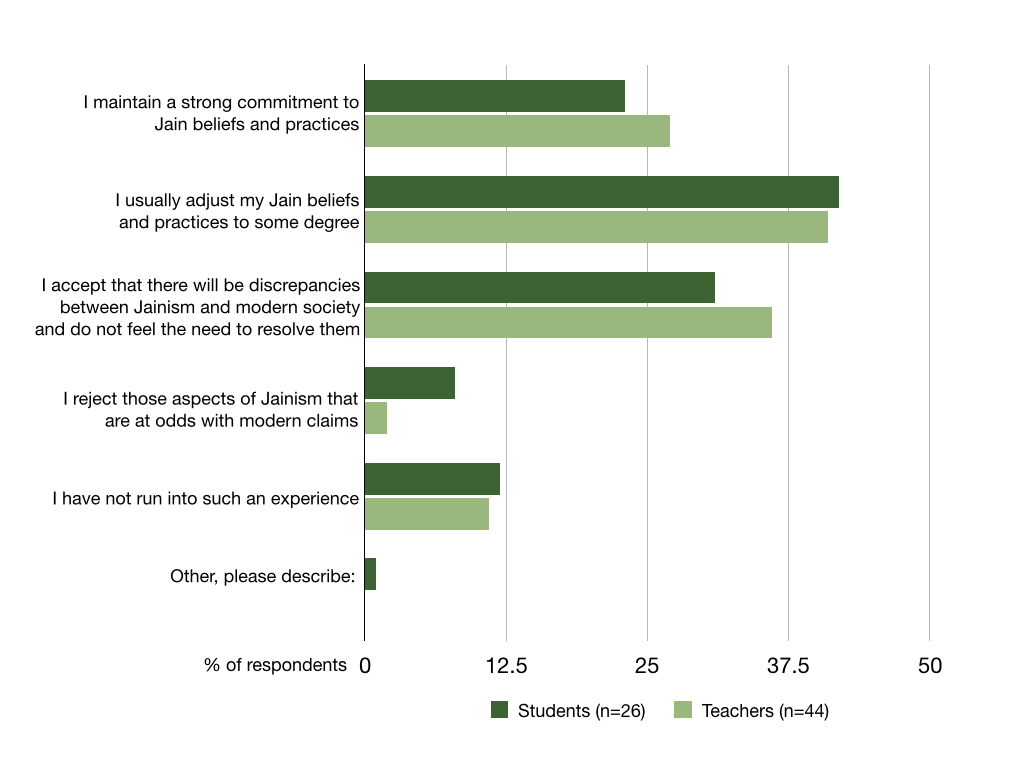

Additionally, a significant percentage of students and teachers also reported adjusting their Jain beliefs and practices to some degree when an aspect of the Jain tradition conflicts with a claim of modern society (S 42%, n=26; T 41%, n=44);. Those respondents who opt to adjust their Jain belief outpace those who “maintain a strong commitment to Jain beliefs and practices” (S 23%; T 27%), as well as those who “accept that there will be discrepancies between Jainism and modern society and do not feel the need to resolve them” (S 31%; T 36%) (Figure 2.2). Pathshala also appears to have limited influence on helping participants consider the ethical dilemmas of their present or future employment specifically (S 45%, n=22; T 45%, n=42).

U.S. pathshala curriculum effectively transmits the inherited history, cosmology, philosophy and ethical practices of Jainism as an ancient tradition relevant to the lives of modern Jains. At the same time, pathshala employs the neo-orthodox emphasis on rational, independent thought. Consequently, one can “believe” in the Jain worldview as valuable and virtuous without articulating a specific creed or assenting to ethical prescriptions. For pathshala students and teachers, “believing” in Jainism may also mean questioning the tradition. For instance, when presented the statement: “Attending pathshala makes me question whether I really follow the beliefs and practices of Jainism,” the majority of respondents agreed (S 54%, n=26; T 59%, n=44), and a significant minority did not know (S 23%; T 10%). In certain respects, pathshala appears to offer a substantive enough education in the Jain tradition such that participants experience conflicting values and truth claims within the various non-Jain social worlds and knowledge frameworks they inhabit. When it comes to competing truths, it may be the case that pathshala raises more questions than it answers.

Figure 2.2 “When an aspect of the Jain tradition is at odds with a claim in modern society (Choose all that apply):” (S, n=26; T, n=44)

Jain Teachings Promotes Tolerance, Although Pathshala Does Not Specifically Engage Other Worldviews

Pathshala students and teachers overwhelming agree that “Jain beliefs and practices help [them] live harmoniously with other religions” (S 91%, n=22; T 90%, n=42). However, pathshala education was also not a meaningful source of knowledge regarding other religious traditions or worldviews, suggesting that participants do not engage a plurality of religious truth claims in temple education. To the open-ended question: “How do you primarily learn about other religious traditions or philosophical worldviews?,” only a small minority of students listed pathshala as a source (S 6%, n=17; T 0%, n=35). Sources for interreligious learning included friends who identify with other views (S 71%; T 40%), reading books or online sources (S 28%; T 49%), interfaith events (S 6%; T 11%), school courses (S 29%; T 9%), travel or visiting other religious communities (T 14%), television/film (T 14%), parents (T 3%), Jain scholars (T 3%), and the JAINA book on world religions (T 3%).[10]

Although participants do not experience interreligious education as a structured part of the curriculum, striving toward interreligious understanding seems to be a contemporary expression of Jainism’s ancient track record of “cautious 'integration'” (Jaini 2001/1979, 287; Vallely 2006, 99) or “opposition and absorption” of elements within the surrounding Indian society (Qvarnström 2000, 117-118). As I will discuss in the next section, interfaith dialog is one of several topics of interest that students and teachers would like to discuss more in pathshala. It is also important to note that the JAINA Education Committee has published one eighty-page supplementary curriculum book on other religious worldviews titled Essence of World Religions: Unity in Diversity which offers a synopsis of the central beliefs, main teachers/founders, scriptures, history, symbols and holidays of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Shintoism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Islam, and Baha’i. Pathshala teachers can use it at their discretion.

Participants Identify Possible Areas of Growth for Pathshala

A majority of survey respondents reported being “very engaged” (S 55%, n=22; T 81%, n=42) or “somewhat engaged” (S 41%; T 14%) in pathshala classes. This is not altogether surprising, considering that some level of investment in pathshala is likely to be required for any respondent to be willing to complete a 178-question survey on the topic. Participants reported being “actively involved in class discussions” (S 62%, n=22; T 82%, n=42), with a lesser number being “actively involved in planning and events” (S 38%; T 48%). Many participants were also involved with a temple youth group (S 62%, n=22) or adult study group (T 39%, n=42) outside pathshala, indicating an additional level of commitment to temple-based social groups.

Active engagement, however, does not mean that participants are fully satisfied with the experience of pathshala. Approximately one-third of participants sometimes found pathshala “boring or repetitive" (S 32%, n=22; T 36%, n=42), and several had suggestions for its future improvement. Current students, for example, had some interest in contributing to a “redesign of the pathshala class” (S Yes 38%, n=13; Maybe 31%). And when asked: “Do you have any ideas presently that you would like to integrate into pathshala classes?,” students suggested adding discussion, having “more meditation/yoga-based days . . . [in order] to practice the skills that we learn,” learning stutis (praise songs), bringing Jain scholars to talk with students, allowing students to bring non-Jain friends to class, and making use of online learning, such as integrating YJA’s online pathshala curriculum. Teachers also had ideas that they would like to see integrated into pathshala, such as making use of online learning, allowing more time for introspection, arranging group discussions among older students, using digital media, carrying out community service, integrating games for learning and play, comparing Jain/Indian philosophy with Western views, learning the meaning of core sutras, storytelling with moral principles, discussing contemporary issues students are facing, providing more examples of people living out Jain principles, providing more instruction in Indian languages, and organizing a teachers’ workshop.

Similarly, when presented with the question: “What might raise your interest level in pathshala classes?,” students suggested an emphasis on “how we live rather than information and facts,” a desire for students to have input in what is taught, a desire for more activities to be organized and visits made to other places of worship in order to explore interfaith dialog, and a desire to discuss more “taboo topics.” One student stated that: “As a college student, I wish it was easier to go to pathshala classes.” Teachers also offered suggestions about what would raise their interest, including improved class structure, more students, round table discussions, greater peer interaction, social activities, Q & A sessions, hands-on learning, revised teaching materials, better trained teachers, and the opportunity to exploring practical life issues.

Future Topics of Interest

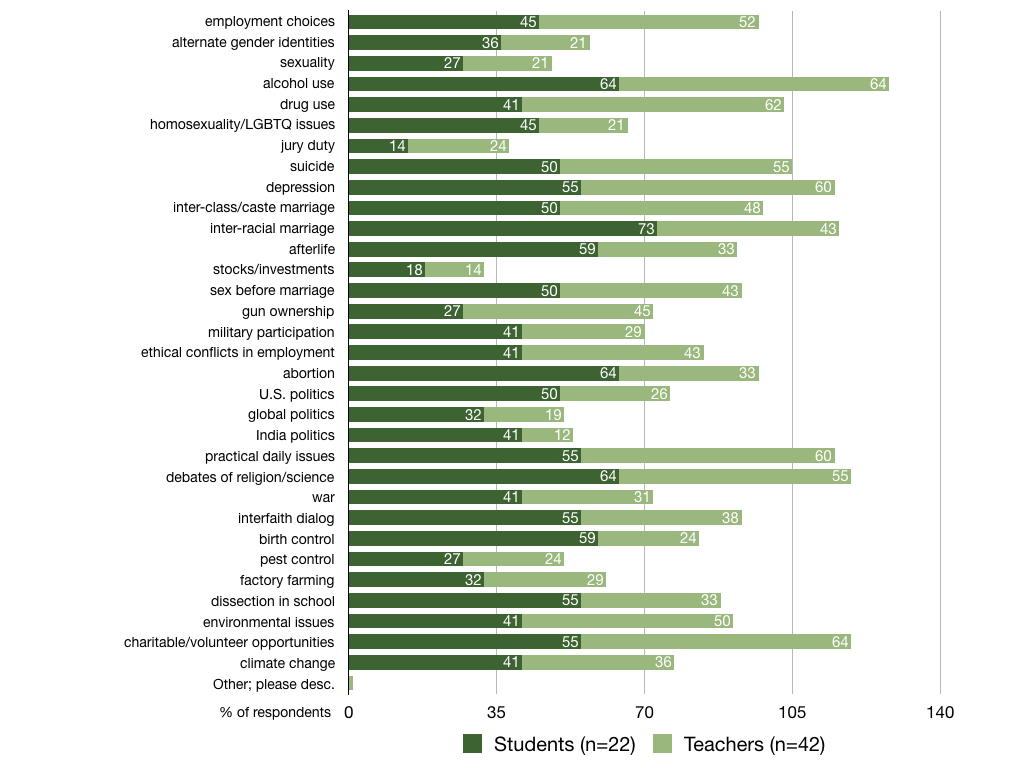

Regarding specific topics that they would like to see covered in pathshala, respondents were asked to choose as many topics as they liked from a list of thirty-two possible issues. For students, the top issues of interest were (Figure 2.3):

- interracial marriage (73%, n=22)

- alcohol use (64%)

- abortion (64%)

- debates of religion and science (64%)

- afterlife (59%)

- birth control (59%)

- depression (55%)

- practical daily issues (55%)

- interfaith dialog (55%)

- local charitable and volunteer opportunities (55%)

- dissection in school (55%)

Teachers prioritized their topics of interest differently, though there are notable areas of overlap:

- alcohol use (64%, n=42)

- local charitable and volunteer opportunities drug use (64%)

- depression (60%)

- practical daily issues (60%)

- suicide (55%)

- debates of science and religion (55%)

- employment/vocational choices (52%)

- environmental issues (50%)

- inter-class/caste marriage (48%)

- gun ownership (45%)

Figure 2.3: “Do you have interest in discussing any of the following issues in pathshala more (Choose all that apply)?” The chart records the percentage of students (n=22) and teachers (n=42) who selected each issue of interest.

Students and teachers had high levels of common interest in discussing issues of alcohol use, charitable/volunteer opportunities, debates of religion and science, depression, marriage (on which more below), and practical daily issues.

On a related open-ended question: “Are there any subjects you would like to discuss more in pathshala classes?,” those students who answered (32%, n=22) desired to: learn about other religions, discuss karma, learn how to shed karma (nirjara), learn stutis and their meanings, discuss current events and how Jainism applies to them, learn about the different life forms described in the Jain universe (jīva vicāra), and learn about the Jain concept of time and universal geography. Those teachers who answered (55%, n=42) desired to discuss: spirituality, ethics, “redesigning Jainism for modern times,” Jain history, the meaning of sutras, current events from a Jain viewpoint, child-related social issues, the Jain way of daily living, global issues, the Hindi language, transitioning to being Jain at college and as an older professional. In addition, they expressed a desire to have a free Q&A time at the end of each class.

Jain Marriage in Diaspora

Although each of these areas of interest could generate productive research, students’ high level of emphasis on marriage (inter-racial, inter-class, and inter-caste) is worth noting here, as it represents a unique diaspora issue that bears on the future survival of the Jain community. Although mendicant initiation requires the eschewal of or departure from marital bonds (Flügel 2006, 338-339), lay Jain householders regularly practice marriage. In Sangave’s sociological analysis of Jains in India, he asserts that marriage among lay Jains is primarily a social convention “based on local customs and not on holy scriptures” (1959, 141); it does not have religious significance akin to Hindu marriage, for example, which aims to beget a son for various ritual purposes (140). These social conventions, however, hold strong sway for Jains, both in and out of India. According to M. Whitney Kelting’s research on Jain wifehood in Maharastra, Jain marriage is still governed by practices of family arrangement based on higher (hypergamous) caste and lateral class, and women often still move into their husband’s family home (2009, 15). While young U.S. Jains are increasingly critical of these traditional practices (“Love and Marriage”), John Hinnells describes pervasive marital pressures among the South Asian diaspora that transcend national boundaries: “However westernized South Asians, young or old, may be, when the time of marriage approaches the force of traditions becomes potent” (Hinnells 6).

The lack of textual and religious significance may be one factor fueling more diverse marriage trends among diaspora Jains that include not marrying at all, marrying later in life, remarrying, marrying non-Jain Indians, or marrying non-Jain Americans. As mentioned above, Shah reports that 70% of Jain children are marrying non-Jain Americans, requiring an increase in social understanding and tolerance among Jain families (2017a). JAINA also reports that “one out of every two Jains will marry a non-Jain” (“Jain Vision 2020”). Although the sources for these statistics are not clear, the acceptance of non-Jains into Jain families seems to be a tenuous trend within “neo-orthodox” Jainism. In a recent book by U.S. Jain layman Sulekh Jain titled An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide, Jain acknowledges that young Jains who did not grow up in insular Jain communities of India “now search for spouses outside the tradition in which they were born and raised” (2016, 193). Rather than condemn this practice, Jain is critical of the conflicts that arise in families due to mixed marriage. “I wonder,” he asks, “how many of us stop and think of ahimsa and anekantavade [the Jain doctrine of many-sided views] here?” (193).

Simultaneously, efforts persist among the diaspora community to foster intra-Jain marriages. Jain Digest, for instance, still offers a section on “Matrimonial Ads,” which runs in conjunction with the website “Jain Milan” that provides “an opportunity for Jain youths between the age of 21 to 42 to meet in person, to make friends, to engage in networking, and to possibly find a life partner” (“About Us”). JAINA also has a “Marriage Information Services Committee” and one of the main purposes of the biennial national JAINA conference is “to provide a platform for young Jains and try to connect them with suitable prospects for marriage” (Mukherjee 2011).

The changing currents of lay marriage can also be seen among mendicant views. Ācārya Tulsī (1914-1997), the ninth mendicant leader of the Terapanthī Ṡvetābara sect initiated the Anuvrat Movement in 1949 to help lay Jains renew their commitment to Jainism in modernity. In one of his books, The Vision of a New Society, Tulsī is adamant that “Times always change,” arguing that Jains too must adapt their philosophies to the present context while maintaining their original spirit (1998, “Personal Testament”); yet Tulsī also strongly defends the joint extended family as a hallmark of Jain marriage (1998, 62-67). A decade later, however, in a book entitled Happy and Harmonious Family, his predecessor, Mahāprajña (1920-2010), emphasizes the need for families and couples to positively co-exist, to harmonize views, and to avoid conflicts over “meaningless conservatism,” without ever mentioning the tradition of joint families, or intra-Jain marriage (Mahapragya 2008, 36). The “who” of the marriage contract is totally absent; only the “how” of negotiated, peaceful relations is stressed.

Pathshala will likely play a role in Jain marriage trends in diaspora. As already mentioned above, many survey respondents claimed that pathshala had or may have an impact on their choice of life partner. JAINA’s “Jain Vision 2020,” describes intermarriage as an opportunity to increase Jain education and outreach. “[W] e want to educate our kids on JWOL [Jain Way of Life]. And if they do decide to marry non-Jains, we want these kids to be so strong, confident and educated Jains,” the statement expresses, continuing:

Through love and care, we want them to teach their non-Jain spouse JWOL. We believe today that only 20% of mixed marriages are living a JWOL and our vision is to expand to 60% of the mixed marriages living a JWOL. To achieve this, we need to come up with specific literature, web-training material for mixed couples so they can appreciate the richness and relevancy of JWOL, without the non-Jain spouse feeling pressured to convert to Jainism. (“Jain Vision 2020”)

In this document, the shared character and ethical orientation underlying a marriage seems more important than the particular ethnicity, class, or caste of either partner. At the same time, the production of materials for mixed Jain couples is an education strategy to keep Jains connected to an already small minority community, to share the Jain Way of Life with others, and to increase the chance of future children being raised with Jain principles, if not cultural traditions.

Future Activities of Interest

When asked to create an open-ended list of specific activities they would like to see offered in pathshala, those students and teachers who responded listed community service (S 57%, n=7; T 48%, n=21) more than any other activity, followed by yoga,[11] game-based learning, and field trips. The relationship between community service and pathshala varied among respondents. A majority of students and teachers agreed that “my pathshala provides me the motivation to pursue community service opportunities on my own” (S 58%, n=26; T 61%, n=44), with such service being defined as “related to people, children, animals, environment, or politics, etc.” However, a noticeably larger percentage of teachers (68%, n=44) than students (50%, n=26) agreed that pathshala provided greater opportunities for local volunteerism . A smaller group felt pathshala offered access to national or international service opportunities (S 31%; T 25%). Some felt the temple, rather than pathshala, offered volunteering possibilities (S 23%; T 14%), while a small minority felt that neither pathshala nor temples offered opportunities for service (S 8%; T 11%). As already mentioned above, many respondents had a desire to learn rituals during pathshala in an Indian language (S 64%, n=22; T 57%, n=42) or in English (S 68%; T 64%), as well as bhajans and stavans in an Indian language (S 72%; T 69%) and, to a lesser degree, in English (S 45%; T 48%). Teachers expressed a greater desire than students that physical yoga practice be integrated into pathshala (S 41%, n=22; T 74%, n=42), while teachers and students both had a high preference for learning meditation in pathshala (S 73%, n=22; T 81%, n=44) (see footnote 11).

Training Future Teachers

Not surprisingly, most teachers believed that it was important to “recruit a new generation of pathshala teachers” (T 81%, n=42). Half of the students agreed (S 50%, n=22), although many had also not considered the question before (27%). Teachers were slightly more interested than students in seeing “a formal certification for newly recruited pathshala teachers” (S Yes 27%, No 36%, n=22; T Yes 45%, No 17%, n=42), although many teachers and students had not considered this option previously (S 36%; T 26%). Those interested in a certification for current pathshala teachers were asked to list “the most important measurements you would like to see assessed.” Students most frequently suggested real life applicability, followed by an energetic desire to teach, willingness to discuss current issues, ability to excite students, and understanding of basic rituals among all Jain sects. Teachers most frequently suggested the ability of teachers to positively connect with students, followed by the extent to which they were knowledgeable, open-minded, and able to offer an example of living Jain principles in their own lives.

The need for more teachers is addressed by respondents throughout the survey in various ways, for instance, via teachers’ comments on what could be improved. The need for future teachers becomes clearer when it is considered that only 3% (n=42) of teachers affirmed that “I would like to be more involved” when asked about their present contribution to pathshala, compared to 31% (n=22) of students. In general, students expressed interest in shaping the future pathshala program. As mentioned above, some have suggestions concerning activities that could be integrated into classes. Of those students who had never taught before (n=13), over one-third stated that they would like to teach in the future (38%).

Maintaining Student Interest through College: The Role of Young Jains of America

One particular concern with the continuity of pathshala is how to maintain student interest during college. The present pathshala curriculum is primarily geared to Pre-K through high school students, with some temples offering classes for adults, although often those with families. Among those who had stopped attending pathshala for some reason, college was listed on an open-ended question by both students (S 44%, n=9) and teachers (T 18%, n=22), with many students describing a lack of access to pathshala during their college years, when they are away from their home communities.

Young Jains of America (YJA), which was established in 1991 as an organization to serve Jains aged 14-29, continues to play a growing role in keeping college-age and early-professional Jains connected to the community. In addition to holding biennial youth conventions, YJA elects a new Executive Board each year to nurture leadership, and runs various online forums such as the new YJA online Pathshala started in February 2017 (“YJA”). The online pathshala is comprised of a growing collection of three-minute videos (addressing nine distinct topics at the time of this writing), a short self-check survey to gauge understanding, and other resources such as flash cards and links to related pop-culture articles.

Among respondents who had participated in YJA events, the following two statements shared equal top ranking among students when asked about the most significant benefits: “I have grown in my personal commitment to a Jain way of life” (35%, n=17), and “I have made friends across the country” (35%). In response to the same question, the most frequent response by teachers was: “I have gained confidence in applying Jain values in my daily life” (18%, n=19), followed by: “I have grown in my personal commitment to a Jain way of life” (16%) and equally “I feel more comfortable in developing my own personal understanding of Jainism” (16%).[12] Current students expressed some ambivalence when asked if they would like to be involved in pathshala in some way after college, with some agreeing, but the majority undecided (S Yes 38%, No 15%, I don't know 46%, n=13). Both temple pathshala, as well as YJA’s online pathshala, may play a critical role in keeping young Jains connected to their communities in the formative years during and after college.

Part 2 Conclusion

Pathshala provides multiple strategies for minority Jains to navigate their multicultural identity in non-Jain contexts. While pathshala perpetuates a universal version of Jainism that is more intelligible and flexible outside of India, classes also offer Jain-specific teaching regarding diet, fasting, and rituals. Pathshala fosters national relationships among Jains, and influences marital choice and the desire to keep children connected to temple education in the future. While pathshala supports independent reasoning, intellectual investigation, and interfaith cooperation, pathshala teachers and classes are not a source for engaging with the content of alternate truth claims of society or the alternate truth claims of other religious and/or philosophical traditions. Students and teachers are invested in strengthening the future of pathshala and have ideas for its success and development. Participants were interested in discussing many topics in pathshala—with overlapping student/teacher interest in issues of alcohol use, volunteer opportunities, debates between science and religion, depression, and marriage, as well as practical daily issues. Marriage trends present a particularly salient area for future research, given the high degree of student interest, its role in Jainism’s survival in diaspora, and the impact that pathshala may have in supporting marriage between Jains and with non-Jains. Participants also had a high interest in community service activities, learning and performing rituals, as well as a desire to integrate yoga and meditation in pathshala classes. Teachers had a high desire to recruit future teachers, while over one-third of students who had not taught before expressed interest in teaching in the future. The period of time after high school offers an opportunity for pathshala to develop programming or online content to keep young Jains connected during college and transition into professional life.

Bibliography

“About Us.” n. d. Jain Milan. Accessed February 9, 2019 at http://www.jainmilan.org/about.php

Auckland, Knut. 2016. “The Scientization and Academization of Jainism.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84, no. 1: 192-233.

Banks, Marcus. 1991. “Orthodoxy and Dissent: Varieties of Religious Belief among Immigrant Gujarati Jains in Britain.” In The Assembly of Listeners: Jains in Society. Michael Carrithers and Caroline Humphrey (eds.). New York: Cambridge University Press: 241-260.

Bumb, Nikhil. 2010. “Jain or Hindu? Finding a Distinct Religious Identity in a Multi-Faith Society.” Young Minds. December 1. Available at https://youngminds.yja.org/jain-or-hindu-finding-a-distinct-religious-identity-in-a-multi-faith-society-656aecfadd85

Chaliand, G. and J. P. Rageau. 1995. The Penguin Atlas of Diasporas. New York: Viking.

Chapple, Christopher Key (ed.). 2016. Yoga in Jainism. New York: Routledge.

Donaldson, Brianne. 2016. “From Ancient Vegetarianism to Contemporary Advocacy: When Religious Folks Decide that Animals Are No Longer Edible,” Religious Studies and Theology 35 (2): 143-160.

_____. 2019. “Jainism and Darwin: Evolution Beyond Orthodoxy.” In Asian Religious Response to Darwinism. C. McKenzie Brown (ed.). Springer, 2019; forthcoming.

Dundas, Paul. 2002. The Jains, 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge.

Evans, Brett. 2012. “Jainism’s Intersection with Contemporary Ethical Movements: An Ethnographic Examination of a Diaspora Jain Community,” The Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography 2 (2). Accessed January 2018. Available at https://ojs.library.dal.ca/JUE/article/viewFile/8146/6982

Flügel, Peter. 2006. “Demographic Trends in Jaina Monasticism.” In Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues. Peter Flügel (ed.). New York: Routledge: 312-398.

Hinnells, John R. 2000. “South Asian Religions in Migration: A Comparative Study of the British, Canadian, and U.S. Experience.” In The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. Harold Coward, John R. Hinnells, and Raymond Brady Williams (eds.). Albany: State University of New York Press: 1-11.

Jain, Andrea. 2016. “Jain Modern Yoga: the Case of Prekṣā Dhyāna.” In Yoga in Jainism. Christopher Key Chapple (ed.). New York: Routledge: 229-242.

Jain, Yogendra. 2007. The Jain Way of Life: A Guide to Compassionate, Healthy, and Happy Living. JAINA.

“Jain Vision 2020: To Live and Promote a Jain Way of Life—Our Vision for North American Jains, Jain Organizations, and Jainism.” n. d. JAINA. Available at https://www.jaina.org/page/Vision

Jaini, Padmanabh S. 2001/1979. The Jaina Path of Purification. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

______. 2010a. “Fear of Food: Jaina Attitudes on Eating.” In Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Padmanabh S. Jaini (ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: 281-296.

______. 2010b. “Is There a Popular Jainism?” In Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Padmanabh S. Jaini (ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: 267-279.

Kelting, M. Whitney. 2009. Heroic Wives: Rituals, Stories, and the Virtues and Jain Wifehood. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kurien, Prema. 2007. A Place at the Multicultural Table: The Development of an American Hinduism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Laidlaw, James. 1995. Riches and Renunciation: Religion, Economy, and Society among the Jains. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

“Love and Marriage.” n. d. Harvard University, The Pluralism Project. Available at http://pluralism.org/religions/jainism/issues-for-jains-in-america/love-and-marriage/

Mahapragya (Mahāprajña), Acharya. 2008. Happy and Harmonious Family. Ladnun, Rajasthan: Jain Vishva Bharati.

Mukherjee, Ruchi. 2011. “Jaina Convention Meets for Networking and, Maybe, Marriage?” Houston Culture Map, July 6. Available at http://houston.culturemap.com/news/city-life/07-06-11-jain-convention-meets-for-networking-and-maybe-marriage/.

Qvarnström, Olle. 2000. “Stability and Adaptability: A Jain Strategy for Survival and Growth,” in Jain Doctrine and Practice: Academic Perspectives. Edited by Joseph T. O’Connell. Toronto: University of Toronto, pp. 113-135.

Rai, Rajesh and Peter Reeves. 2009. “Introduction.” In The South Asian Diaspora: Transnational Networks and Changing Identities. New York: Routledge: 1-12.

Reynall, Josephine. 2006 “Religious Practice and the Creation of Personhood Among Śvetāmbar Mūrtipūjak Jain women in Jaipur. In Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues. Peter Flügel (ed.). New York: Routledge: 208-238.

Sangave, Vilas. 1959. Jaina Community: A Social Survey. Bombay, India: Popular Book Depot.

Scholz, Sabine. 2012. “‘The Jain Way of Life’: Modern Re-Use and Reinterpretation of Ancient Jain Concepts” in Re-Use: The Art and Politics of Integration and Anxiety. Julia A. B. Hegewald and Subrata K. Mitra (eds.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications: 273-287.

Shah, Bindi V. 2014. “Religion in the Everyday Lives of Second-Generation Jains in Britain and the USA: Resources Offered by a Dharma-Based South Asian Religion for the Construction of Religious Biographies, and Negotiating Risk and Uncertainty in Late Modern Societies,” The Sociological Review 62 (3): 512-529.

Shah, Pravin. 2017a. “Pathshala: The Next Generation of American Jains” The South Asian Times. August 7, 2017. Available at http://thesouthasiantimes.info/news-Pathshala_The_Next_Generation_of_American_Jains-180593-Art-Books-37.html

“Top Meat Consuming Countries In The World.” n. d. World Atlas. Available at https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/top-meat-consuming-countries-in-the-world.html

Tulsi, Acharya. 1998. The Vision of a New Society. Churu, Rajasthan: Adarsh Sahitya Sangh.

Vallely, Anne. 2008. “Moral Landscapes: Ethical Discourses among Orthodox and Diaspora Jains” in A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion, 2nd Edition. Michael Lambek (ed.). Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing: 560-572.

_____. 2004. “The Jain Plate: The Semiotics of the Diaspora Diet” in South Asians in Diaspora: Histories and Religious Traditions. Knut Jacobsen and Pratap Kumar (eds.). Leiden: Brill Publishing: 1-22.

Williams, Raymond Brady. 2000. “South Asians in the United States—Introduction,” in The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. Harold Coward, John R. Hinnells, and Raymond Brady Williams (eds.). Albany: State University of New York Press: 211-218.

“YJA Pathshala.” n. d. Young Jains of America. Accessed April 12, 2018. Available at https://yja.org/pathshala

Brianne Donaldson is the Fellow in Jain Studies at Rice University in Houston, Texas. She is the author of Creaturely Cosmologies: Why Metaphysics Matters for Animal and Planetary Liberation (2015), which examines the world visions of Jainism and Whitehead’s process-relational philosophy, as well as the edited collections Beyond the Bifurcation of Nature: A Common World for Animals and the Environment (2014), The Future of Meet without Animals (with Christopher Carter) (2016), and Feeling Animal Death: Being Host to Ghosts (with Ashley King) (2019).

[1] Williams provides the Śvetāmbara list of lay occupations in a hierarchy of desirability as: trade, practice of medicine, agriculture, artisanal crafts, animal husbandry, service of a ruler, and begging. The Digambara list includes: trade, clerical occupations, agriculture, artisanal crafts, and military occupations (1991, 122).

[2] I have made small changes to these sentences to standardize the grammar and make the parts of speech consistent. Beyond these minor alterations, the sentences—here and throughout the Part 1 and Part 2 analyses—reflect the direct responses of participants.

[3] Jaini describes “popular Jainism” as those “practices within Jaina society that can be considered inconsistent with the main teachings of the religion, but so thoroughly assimilated with them now that they are no longer perceived as alien” (2010b, 267).

[4] Question: “If you have ever encouraged a friend/s to adopt Jain beliefs or practices, which of the following apply?” (a) I ask them to consider becoming Jain (0%); (b) I ask them to consider certain practices (such as nonviolence, vegetarianism, or meditation, etc.) because the practices are Jain and because the practices are correct (S 4%, n=26; T 18%, n=44); (c) I ask them to consider certain practices (such as nonviolence, vegetarianism, or meditation, etc.) because the practices are correct, but not necessarily because the practices are Jain (S 58%; T 41%); (d) I have not considered this before (S 27%; T 30%); Other; please describe: (S 12%; T 11%).

[5] “Cataphatic” refers to activities that positively defines what a Jain is or does, rather than a negative definition of what a Jain is not or does not do (“apophatic”).

[6] For a description of Jain food ethics see Jaini 2010a.

[7] A gradually increasing segment of Jains—primarily in diaspora countries—advocates the ethical-political position of veganism as the modern equivalent of Jain food ethics rooted in ahiṃsā. Groups such as U.S.-based Vegan Jains and U.K.-based Jain Vegans host events to educate Jain about the cruelty of modern dairy production in terms of forced impregnation, the removal of female calves, the killing of male calves, as well as the effects on workers and the environment. As of 2018, Young Jains of America serves only vegan meals at their conferences. Likewise, the large Jain Center of Southern California also announced in 2018 that it would only serve vegan meals in their temple kitchen. The majority of respondents responded affirmatively to the statement: “I consider veganism (no meat, dairy, eggs, leather, or fur) an expression of Jain dietary ethics” (S 81%, n=26; T 73%, n=44). See Vallely 2004, Donaldson 2016, Evans 2012.

[8] I note these familial roles in order to mark the role of women in transmitting Jain identity. See Kelting (2009) and Reynall (2006).

[9] In Jain metaphysics, an individual jīva will inhabit a body that is born into one of four birth classes: human, animal, plant, or heaven or hell being. The various layers of heavens and hells are considered part of the karmically-bound universe, meaning that a being can leave these places on subsequent rebirths. While positive or negative karma may result in one being born in heavens or hells respectively, these states of habitation are seen as self-inflicted rather than determined by any outside deity or judge, and the states are temporary, not a final landing place after death. Beings can only achieve liberation from the human-born state, where the mixture of positive and negative experiences requires meaningful karmic choice.

[10] Shah, Pravin (ed.). 1994. Essence of World Religions: Unity in Diversity. Printed by JAINA Education Committee and available free online.

[11] Students did not specify what they meant by yoga or meditation, aside from the one remark describing “physical yoga” mentioned above. From my own observation at Jain pathshalas, “yoga” has a broad range of meanings, including sitting in a physical posture at the start of class, being instructed by a teacher to take a deep breath as the first step of a class, practicing a posture that will be used during the annual Pratikramaṇa ritual during the holiday of Paryuṣana, discussing meditation vows or exercises (sāmāyika or dhyāna), or spending short periods for “introspection” or “quiet reflection.” One class of young Jains also did a group “yoga” activity consisting of “meditators” who were to remain quietly focused while “disturbers” yelled and made a racket to distract them as part of a lesson on mental control and ahiṃsā. Among many other possible meanings, the term “yoga” could also be used to refer to specific teachings by Prekṣā Dhyāna (mentioned above and in Part 1) or to meditational practices within Śrīmad Rājacandra meetings, for example. See Chapple (ed.) Yoga in Jainism (2016). These educational techniques are a rich area for future research.

[12] In response to the question: “If you have participated in events associated with Young Jains of America, which of the following would you say is true? (Choose top three),” the most frequent responses were: “I have learned more about the Jain tradition” (S 19%; T 11%); “I have grown in my personal commitment to a Jain way of life” (S 35%; T 16)%); “I have gained exposure to a diversity of Jain beliefs and practices around the country” (S 15%; T 14%); “I have gained confidence in applying Jain values in my daily life” (S 23%; T 18%); “I have gained confidence in explaining the Jain tradition to non-Jain friends or colleagues” (S 19%; T 11%); “I feel more comfortable in developing my own personal understanding of Jainism” (S 12%; T 16%); “I am able to interpret which Jain values are most important to me and which are less important” (S 15%; T 11%); “I have made friends across the country” (S 35%; T 57%).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.