Abstract

The Gee clan of Houston is the largest and most prominent network of Chinese Americans in Houston. Linked together by a commonly shared last name, Gee (朱), and not always by blood, it is remarkable in that its members actively work to keep the ties strong, especially the younger generation, whose cultural reference is thoroughly American. This article examines how the Gees parlayed the traditional Chinese affinity for associations based on the same surname or place of origin into a hybrid model adapted for maximum efficacy in the new world. Led by a small group of generous and resourceful elders who put down roots in the Bayou city, the Gees rose from humble beginnings, endured the Jim Crow restrictions on non-whites, and attained great social, financial, and political heights. A brief discussion on the migration and assimilation patterns of overseas Chinese offers a conceptual framework with which to understand the settlement process of this remarkable group of individuals. The following stories are derived from interviews in HAAA, and form the basis of a planned in-depth study of the Gee clan.

I. Introduction

Scholars of Chinese migration have referenced classical theories of international migration and created their own syncretic framework to conceptualize the movement of people outward from China. The narrative of classic migration theories begins with E. G. Ravenstein’s seminal “Laws of Migration,” first created to study British migration in 1885. His laws were applied to international migration four years later and inspired the use of neo-classical economic models to explain rural-urban migration.[1] In 1966, Everett S. Lee’s formulated the push-pull theory in an attempt to create a unified model. The push-pull theory of migration proved highly popular, with its emphasis on four elements of migration: factors associated with the place of origin, those associated with the destination, intervening obstacles, and personal factors.[2] Since then, the rapidly changing social, political and economic conditions associated with international migration have spurred on the development of a plethora of migration theories. Scholars have concluded that while no single theory can define the process of migration, each theory has something to contribute in conceptualizing migration.[3]

Wang Gungwu, perhaps the most prominent contemporary authority on Chinese migration,[4] maintains that there are four basic patterns of Chinese movement overseas: merchant activities (huashang 華商), “coolie” labor (huagong 華工), sojourning (huaqiao 華僑), and re-migration (huayi 華裔). Wang considers trade to be the earliest and most enduring or “resilient” pattern, observing that Chinese merchants would either go abroad themselves or send their family members abroad, and once a business had been established there, they would sometimes put down roots locally. The term “coolie” primarily refers to “peasants, landless laborers and the urban poor” who went abroad for relatively short periods in the span of time between the 1850s and the 1920s and generally returned to China. The term “sojourner” usually refers to people who move from one cultural environment to another, but who, like the “coolies” described above, do not plan to stay there.[5]

At times, the term huaqiao has been used to describe all overseas Chinese, past and present, but Wang employs it in a much narrower sense. In his view, huaqiao in the first half of the twentieth century tended to be individuals with strong political feelings who were predominantly concerned either with Chinese national politics and its “international ramifications,” “community politics” in the areas in which they resided, or “the politics of non-Chinese hierarchies, whether indigenous or colonial or nationalist.”[6] The huayi pattern in Wang’s scheme refers to the post-1950s movement of people of Chinese descent from one foreign country to another.[7]

Not surprisingly, Wang’s views have not been universally accepted by other scholars. In the first place, the term “sojourner” has been highly contested. Quite apart from its overly restrictive use in Wang’s interpretive framework, Philip Q. Yang has called into question what he considers to be its tendency to promote a simplistic stereotype of the Asian American as the “perpetual foreigner.” In an article titled “The ‘Sojourner Hypothesis’ Revisited,” Yang argues that the old notion of the “sojourner” reduces the complex motives and experiences of early Chinese immigrants to a single dimension, and that it is particularly inappropriate as a way of describing Chinese immigration patterns in the period after 1965.”[8]

Leo Suryadinata, for his part, has expressed discomfort with Wang’s entire interpretive paradigm, suggesting that it too often “stresses continuity rather than change,” and that the huashang category is “too liberal and inclusive,” blurring “the boundaries between trade and non-trade.” He argues, moreover, that the first three patterns tend to overlap, and that Wang’s quasi-chronological approach is therefore not particularly useful as an “analytical tool.”[9] Adam McKeown, for his part, has called for “a reformulation of the division of Chinese migration into the trader, coolie, sojourner, and descent patterns,” on the grounds that Wang’s conceptions of these “patterns” is not at all clear. He asks, for example, whether Wang’s scheme is “meant to depict social structures or the orientation of individual migrants.”[10] Other scholars have suggested paradigms of understanding that emphasize the multi-faceted way in which immigrant communities develop “around the edges and between gaps” in a given cultural environment.[11]

McKeown’s perspective on Chinese immigration is particularly valuable for its suggestion that concepts such as “transnationalism,” “globalization,” and “the deterritorialized nation state” may provide a more satisfactory way of approaching issues of Chinese movement, organization and identity than the older idea of “streams of people merely feeding into or flowing along the margins of national and civilizational histories.” He argues, in other words, that a “diasporic” approach to immigration can “complement and expand upon nation-based perspectives by drawing attention to global connections, networks, activities, and consciousnesses that bridge these more localized anchors of reference.”[12]

Of course, the very notion of applying the concept of “diaspora” in reference to the transnational movement of Chinese migrants is itself a matter of considerable debate––not least because the term carries the moral weight associated with the long-standing theme of Jewish forced exile. But, in McKeown’s view, diaspora is a “signifier of multiplicity, fluidity, wildness, hybridity and dislocations of modernity.” The term is useful because it highlights diversity and focuses on “links and flows.”[13] As one example of such links, flows and networks, McKeown notes the commodification of Chinese migrant travel, which often involved payment for “steamer tickets, false identities, access to consuls and visas, successful medical exams, citizenships, human smuggling opportunities, and witnesses who could claim to be a migrant’s mother or to have known him when he was a babe in arms.”[14] As McKeown points out, these activities were often subversive to nation states: “They undermined immigration laws and other barriers against mobility designed to preserve territorial and cultural integrity, and introduced residents who might have no interest in loyalty and integration into the locale.” At the same time, however, he acknowledges that diasporic networks cannot be fathomed “without some understanding of the national borders that shaped this movement.”[15]

In short, McKeown attunes us to the ways that the “practices and ideologies of migration are embedded in larger global trends and transnational activities, with different aspects developing and coming to the forefront at different times.”[16] McKeown therefore decides on a mixed vocabulary of “diaspora, transnationalism, and migration, whatever is most appropriate in developing a particular aspect of global perspective.”[17] With this historically-grounded and dynamic approach to immigration in mind, let us now explore chronologically some of the ways that Chinese travelers have made their way to the United States, some of the challenges they have faced, and some of the strategies they have employed in making new lives in a foreign land.

II. Chinese Immigration to the United States: A Brief Overview

As part of a truly global pattern of migration, the nineteenth century witnessed a massive exodus of Chinese to all corners of the world. The greatest outflow of Chinese in this period occurred in the years 1851–1875, as the social and political unrest from the two Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1860) and the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) created massive human misery, impelling people to leave their homes in South China and seek better lives abroad. In response to this situation, as McKeown has indicated, a coordinated system for sending emigrants overseas became available to people in the coastal regions. Recruiters attracted Chinese laborers; forgers supplied fake forms of identification; “witnesses” were hired to vouch for supposed family kinships. In all, about ten million émigrés left the southern regions of Guangdong, Fujian, Hong Kong and Macao, and the majority settled in Singapore and Malaysia.[18] Meanwhile, news of the discovery of gold in California in 1848 reached China in just a few days, and by 1854, approximately 24,000 Chinese had crossed the Pacific Ocean to America’s Western frontier seeking new economic opportunities.[19] They worked in gold mines, supplied labor for industries and infrastructure projects (The Central Pacific Railroad Company employed about fifteen thousand Chinese to construct the Transcontinental Railroad), and, after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, sometimes took jobs that had formerly been assigned to slaves.

When the California gold rush ended and work on the transcontinental railroads dried up, the Chinese found employment wherever they could––in cotton fields, wool mills, and cigar, shoe, and garment factories; they worked in laundry shops and grocery stores, and as houseboys.[20] Their willingness to do menial labor and to work for lower wages caused growing resentment among members of the white male workforce, particularly during the economic downturn of the 1870s. A series of anti-Chinese immigration laws ensued, beginning with the 1875 Page Law restricting the entry of Chinese women, and continuing with the 1880 Angell Treaty suspending the immigration of Chinese laborers as agreed in the 1868 Burlingame Treaty. Ultimately, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barring entry of all Chinese, except for students, businessmen and diplomats, along with its indefinite extension in 1904, virtually ended Chinese immigration to the U.S. for more than sixty years.[21] Yet, despite all the legal and practical obstacles involved, some 175,000 Chinese immigrants passed through Angel Island Immigration Station near San Francisco between 1910 and 1940.[22]

The precarious existence of the Chinese immigrant was dependent on judgments in four legal arenas: federal immigration law, federal naturalization law, state statutes and city ordinances, and proof of citizenship for employment and procurement of certain services.[23]

Aside from children born in America, who automatically became U.S. citizens, Chinese immigrants were denied the possibility of obtaining American citizenship from 1882 to 1943.[24] Deprived of legal status, being neither white nor black, the Chinese immigrants existed in a state of legal limbo. They resorted to time-honored devices for protection and support. The Page Law and subsequent exclusion laws prevented the immigrants from being joined by their families, who would have been the most important source of shelter and aid. But even in the absence of blood relatives, there were mechanisms by which overseas Chinese could advance their interests––namely, relationships based on other types of affiliation. Such ties were known as guanxi.

Guanxi is generally understood as a set of interpersonal relationships that may include either patron-client or peer-to-peer ties, based on mutual interest and benefit. Reciprocity is expected, as “each party can ask a favor of the other with the expectation that the debt incurred will be repaid sometime in the future.”[25] Guanxi relationships extended (and still extend in most Chinese environments) not only to affiliations based on lineage, but also to marriage ties, family friendships, shared areas of origin, and shared educational experiences. Sworn brothers enjoyed a special sort of guanxi, and even people with the same family name felt a certain connection with one another. Most forms of guanxi “implied a superior-inferior relationship in which the ‘junior’ person owed loyalty, obedience, and respect, while the ‘senior’ owed protection and assistance in advancement.”[26]

In an effort to circumvent restrictive immigration policies, many early settlers were moved to help anyone coming from their home villages in China, often without the existence of any blood relationship. This gave rise to the phenomenon of the “paper son,” a person seeking to come to the United States by falsely claiming to be the son of a Chinese American citizen. This phenomenon mushroomed after the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, when local immigration records were destroyed by fire. This event enabled Chinese migrants to assert that they had been born in San Francisco and to claim as fellow citizens “sons” who had actually been born in China.[27]

But the overseas Chinese in America also explored other legal means to gain leverage in an increasingly hostile environment. In 1895, for example, an organization called the Native Sons of the Golden State was formed to help Chinese Americans fight for their civil rights.[28] The U.S. National Archives hold thousands of case files brought in both circuit and district courts during the late 1800s and early 1900s contesting the exclusionary actions of Federal immigration officials targeting the Chinese. Files dealing with such court cases are interspersed among others concerning court cases from civil, criminal, and admiralty courts and court commissioners’ files.[29]

Meanwhile, in large urban Chinatowns, clans/lineages, associations with memberships based upon shared surnames or places of origin, as well as groups with common interests (generically known as huiguan) lent money, mediated disputes, provided housing and educational opportunities, assisted members in gaining and maintaining employment, provided health, funeral and other services, and protected those who lacked family support.[30] Often described as “benevolent associations,” and usually led by successful merchants in the early stages of their development, such non-lineage organizations represented the Chinese community to the outside world, and regulated the economic activities of their members, including the establishment of legal trade monopolies.[31] Illegal activities, such as opium dens, gambling establishments and prostitution rings were generally under the control of sworn-brotherhood associations known as “tong” (lit. “halls”).[32] Lineage groups, for their part, were generally small, and had a less public profile than huiguan.[33]

In time, and especially after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese associations banded together to form larger and more powerful social and economic units. On November 19, 1882, for example, encouraged by the Chinese consul-general, Huang Zunxian, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association was established in San Francisco with the express purpose of combatting anti-Chinese legislation and providing legal assistance to Chinese migrants suffering from discrimination.[34] As in other areas of their lives in America, Chinese immigrants adapted time-honored institutions and mechanisms to new situations.

Official intervention in the affairs of overseas Chinese began with the late Qing dynasty’s establishment of consulates in various host countries in order to protect the interests of its subjects and encourage their continued involvement with China.[35] Ironically, however, a number of overseas Chinese supported revolutionary causes, including the movement that ultimately toppled the Qing dynasty in 1911. Following the 1911 Revolution and the establishment of a constitutional republic, the Guomindang, or Nationalist Party, found overseas Chinese merchants to be a lucrative fundraising source. Barred from engaging in political activities in their new homelands, the overseas Chinese responded to the solicitations of the politicians back home, investing in schools, building roads and houses in their home villages, and in return receiving honorary awards for their efforts.[36] In stages, Chinese migrants began to acquire identities that were not necessarily based on lineage ties or other traditional forms of association. This did not mean, of course, that such ties were no longer important, but it seems clear that an overarching sense of “Chineseness” began to develop over time, in part as a reaction to the growth of Chinese nationalism.[37]

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was finally repealed in 1943––primarily because China and the United States had become allies in the midst of World War II.[38] But it was not until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that migration pathways were opened significantly for non-European immigrants. From that point onward, Chinese immigration patterns and Chinese American lifestyles became ever more complex––not least in terms of “assimilation,” a deceptively simple-sounding term that masks a wide variety of cultural options.[39] To be sure, some aspects of the Chinese American experience have remained more or less constant, including the tendency to rely on guanxi, and the use of what has sometimes been described as ethnic capital––that is, the application of ethnic-specific financial, human and social capital within networks of affiliation.[40] But with the repeal of the Chinese exclusion acts and the removal or lowering of many social and economic barriers after 1965, we see new patterns of settlement and new forms of political, social, economic and cultural activism.[41] For instance, the newer and more affluent immigrants choose not to live in Chinatowns but in Chinese “ethnoburbs,” a new form of suburban middle-class immigrant community.[42] These new ethnic enclaves, their services catering not only to the local co-ethnics, but also to the Pacific Rim, generate distinct structures of political, economic, social and cultural forces that offer an “effective alternative path to social mobility.”[43] And, since the 1960s, changes have taken place in the leadership of Chinese associations as older individuals have been supplanted by “younger, generally better educated” leaders, many of whom “have deeper roots and interests in American society than their predecessors.”[44]

How, we may then ask, do the experiences of the Gee clan of Houston align with this general narrative, and to what extent do they depart from it?

III. Exploring the Gee Family History

Members of the extended Houston Gee clan came to the U.S. in the late nineteenth century, having originated from three counties in Guangdong province, Taishan, Kaiping and Enping. Taishan and Kaiping were part of the “Four Counties” (Siyi), whose residents were on the whole quite poor and who found employment at the time because of the high demand for manual labor in the developing western United States, including Texas.[45] However, contrary to the stereotype of impoverished and helpless immigrants, some members of the loosely-connected Gee family were comparatively well off.[46] In order to survive in the host society, the Gee clan followed the traditional Chinese practice of relying on collective affinity from a shared surname or area of origin to band together (one prominent type of guanxi). They developed a support network involving not only members of the nuclear and extended family, but also others originating from geographically proximate areas, spanning multiple generations.[47] In some instances, in an effort to gain cross-border entry in the face of challenging immigration laws, they constructed myths of “paper” connections, relationships based on a shared last name and shared home base. Inventing “paper sons” and “paper daughters,” as discussed above, was a way to bring hitherto unrelated fellow countrymen into the U.S.

This loosely-structured quasi-kinship network and the Gee Family Association that grew out of it helped its members to advance their immediate financial, social, and political interests, and over time the Gees developed a network of business connections and personal relationships that linked Houston, San Francisco, Hong Kong, and the villages around Taishan and Kaiping. The Gees thus provide one striking example of the complex ways that Chinese migration came to be embedded in larger global trends and transnational activities, with, as McKeown notes, different aspects developing at different times, and in different ways.

The colorful life stories of the extended Gee family contained in HAAA not only embody certain important features of Asian immigrant experiences in America in a general sense; they also reflect Houston’s unique development as a “southern” city. In other words, the specific political, social, economic, legal and cultural landscape of Houston shaped the lives of its Chinese immigrants in ways that have made their stories distinct from those of Chinese Americans in other major cities. On the one hand, the Chinese in Houston faced certain types of racial prejudice that have long characterized the American South; Texas also imposed Jim Crow laws on non-whites, albeit in a laxer manner than was the case in some other Southern states. (For instance, Chinese children could not attend school with white children in Mississippi, but could do so in Houston).[48] On the other hand, Houston is a young and dynamic city, full of possibilities, and a place that has become remarkably cosmopolitan over the last fifty years or so.[49]

In the nine decades of their residence in Houston, the Gees have achieved remarkable success. They began by operating grocery stores and restaurants in segregated neighborhoods of the city, going on to achieve many milestones, such as having a municipal courthouse named after a Gee judge, a Gee being part-owner of Houston’s football team, and a Gee being elected a Texas State Representative with constituents in the wealthiest enclaves of the city. At the same time, the struggle of the Gees against discrimination and their experience of assimilation reflect certain broad patterns in the immigration and labor history of twentieth-century America—and in particular, that of the Southwest. On an individual level, theirs is a tale of survival, grit, intelligent social networking, and wise entrepreneurship accompanied by some good luck. Yet, their stories have hitherto remained lamentably unknown to many, and their memories have risked fading into obscurity.

Aside from the Gee Family Association almanac and a few Chinese American phone directories, there has been little documentation of how the Gee clan developed. In this paper, we use HAAA oral history interviews, letters, menus, and newspaper clippings (some literally rescued from the dumpster), to create family trees for the network of nuclear families, and supplementing and contextualizing these materials with past deed restrictions of Houston neighborhoods, past Texas Civil Statutes, and the 1952 report of an accreditation agency outlining the basic stages of the clan’s development.

Business Networks and Family Associations: The Brothers C.Y. and Wanto Chu

The Gee Family’s success can be attributed in part to three elders who settled in Houston in the early twentieth century: two brothers, C.Y. Chu and Wanto Chu, and Harry Gee Sr., who was not related by blood to the two brothers (Chu and Gee are both alternative transliterations of the same last name, 朱, pronounced Zhu in the Mandarin dialect). C.Y. Chu, or Chu Yu-choi (朱汝才), also known as Chu Gim-sam (朱兼三), was born in 1901 in a village in Taishan County in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong. With a scholarship obtained from Ling Nam College in China, he came to attend Berkeley College in Stanford California, which was a private preparatory institution for business, in 1918. As a newly-arrived Chinese immigrant to the United States, he had at three unusual advantages––a college education, the ability to read, write and speak English, and enough money to live comfortably and to travel.

In a private letter dated 1924, C.Y.’s brother Wanto wrote: “Be sure to work or do business in the United States for three or so years…because only with capital can one plan with ease and establish great authority.” He went on to say, underlining his remarks for emphasis: “Live diligently and frugally, and in several years you will surely earn both fame and fortune.”[50] Such sentiments reflect the Confucian values of Chinese immigrant families that helped them to survive and thrive in a foreign land.[51] After graduation, C.Y. found himself in Texas, where he was hired by a group of Chinese grocers in San Antonio to serve as a Chinese tutor. At the same time, he took courses in bookkeeping at Draughon Business College, which had been established in 1914. Later in 1924 he moved to Houston, opening a grocery store called Quong Yick in the African-American part of the city with a business partner, Mr. Moy. When the long work hours at the store became too much for Mr. Moy, C.Y. bought his partner’s shares and took full ownership of the store.[52]

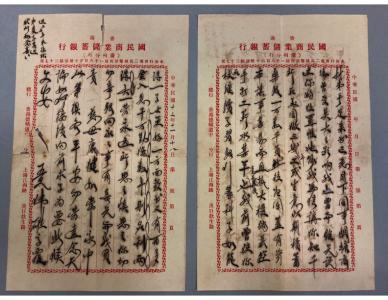

Wanto Chu’s letter to C. Y. Chu

C.Y. had first asked his brother Wanto Chu, who was studying in New York, to come to Houston for a brief visit. Instead, Wanto decided to stay and join C.Y. in business, bringing his family to Houston as well. Together they opened a chain of grocery stores, and welcomed other Chinese newcomers into their homes. Wanto became one of the founders of the Gee Family Association and served as its first president. The initial core membership of the Gee Family Association consisted of young men and their families who were given assistance by the Chu brothers, a testament to how early Chinese migrants relied on both personal and professional relationships (guanxi) to advance and protect their interests.[53] The brothers played a key role in what was essentially an apprenticeship system that involved recruiting Chinese workers from other parts of the United States or directly from China through their various networks. The newcomers would pay the costs incurred through their wages, and eventually C.Y. and Wanto would sell them shares in the grocery chain.

Setting up a grocery store during the 1920s cost about $3000 (equivalent to about $32,000 today), and the Chu brothers’ operations had one Gee member serving as store manager at the front of the shop, and another as butcher at the back.[54] This business model emphasized not only family connections and personal loyalties, but also hard work and accumulated experience. According to Shelton Gee, one of the younger generation of grocers, “[C.Y. Chu] wanted to get the Chinese to start something in, you know, business. But in order to do that, you have to, you know, work your way up.”[55] The combination of apprenticeship and shareholding introduced many new Chinese and Gee members to the grocery business, allowing them, in time, to open their own businesses. For example, the Chu brothers played a key role in aiding Raymond, Henry, and David Gee (see Gee Family Tree) to establish their own individually-owned grocery stores based on an apprenticeship and shareholding model.[56]

Click here for the Gee family tree (in PDF)

Much of the success of early Chinese merchant families such as the Gees depended upon a personal lending network––one that provided immigrants with much-needed capital and resources. As mentioned earlier, such family or “clan networks” expanded beyond strictly kinship and village ties, but remained tightly-knit and based on personal relationships and loyalties. That is to say, sharing of resources and moneylending were not limited to bloodline relatives, or even village associations, but extended to pan-village and semi-regional networks. C.Y.’s personal bookkeeping notes reveal pages of individual transactions involving loans of between twenty and two hundred Hong Kong Dollars (US $10–$100, equivalent to $100–$1000 in today’s money) to individuals who were considered reliable risks by virtue their relationship to him and his networks. Such loans enabled the various Chinese beneficiaries to invest in their own businesses or repay pressing debts. C.Y., Wanto, and a few early Chinese elders thus served as indispensable financiers to the local Chinese population at a time when the Chinese were unable to obtain loans from “white” banks due to unfavorable local regulations.[57]

After the establishment of the first grocery store, Quong Yick, C.Y. and Wanto continued to expand and open up new grocery stores—collectively known as the “Yick Stores” —the names of which, including Jun Yick, Young Yick, and Sun Yick, all shared the word Yick (益), meaning “advantage” or “improvement.”[58] While the word Yick is a popular character for shop names in Canton and Hong Kong to this day, it is hard to imagine that well-educated individuals like the Chus, who were fully conversant with traditional Chinese texts, did not have the following famous saying by Confucius in mind when they made their selection: “There are three types of friends who can improve (益) you: those who are straightforward (直), those who are sincere (諒), and those who have learned much (聞).[59] It is fitting, then, that the Yick Stores became the home base for a community based solidly on the values of straightforwardness, sincerity and abundant knowledge.

Chinese grocers occupied a unique social space and racial niche in the Jim Crow South, which lasted into the 1960s. Living and operating in mainly “colored” areas, the interactions between the Chinese grocers and their African-American neighbors were generally positive. The symbiotic relationship between the new Chinese immigrants and the African-American community was based on several factors. In the first place, neither ethnic group could live or purchase property in the white neighborhoods. Secondly, neither group was eligible for credit from the white-owned banks. Third, African-Americans were generally not allowed to shop in white-owned stores and thus frequented Chinese-owned groceries. Furthermore, Chinese grocers were willing to extend credit to their local customers, whereas the larger grocery stores would not.[60]

As Houston lacked zoning restrictions, and as many people did not own cars, small grocery stores popped up on practically every other block. The start-up capital for a grocery store was relatively small, and such a store could sustain a family if the children worked without pay and the family lived on the premises. A restaurant, however, required much larger operating capital. In 1949, there were forty-two Chinese-owned grocery stores and only about ten Chinese-owned restaurants in Houston, but by the 1980s, there were about one hundred Chinese-owned grocery stores and more than three hundred Chinese-owned restaurants.[61] These statistics reflect the growth of the Chinese population and the increasing affluence of Chinese immigrants over time.

Harry Gee Sr., Entrepreneurship, Network Building and Patterns of Assimilation

A.K.M. Ahsan Ullah, among others, postulates that migrants create networks to decrease the costs and risks of international migration and to enlarge the possibility of movement.[62] As we have seen, the activities of the Chu brothers conform to this basic model. So do the activities of Harry Gee Sr. According to Gordon Gee (his first cousin, once removed), in the 1930s and 1940s, practically “every restaurant” in Houston was opened by Harry Gee Sr.[63] Harry Sr. took care of the Gee “cousins” in his restaurants in much the same way that C. Y. mentored them in the grocery business. His story demonstrates how strong leadership can galvanize an entire community, and how a successful and reputable businessman can rise to lead or establish civic associations to help newly arrived immigrants.

Harry Gee Sr.

Born in Kaiping County in 1895, Harry Sr. came to America at the age of fourteen with money borrowed from a former neighbor, Mr. Gnee Bok, who wired it to him from San Francisco, where Mr. Bok worked as a janitor. Upon his arrival, the young Harry Gee found employment as a dishwasher, needing to stand on a cardboard carton just to reach the sink. Still wearing his hair braided in a long queue, as required of all males by the Qing dynasty, he faced all manner of difficulties and endured all sorts of humiliations, including being attacked by local hoodlums and being called a “Chink.” But he learned English and worked hard. According to Gordon Gee, for the next twenty-eight years, Harry labored twelve to fourteen hours a day, seven days a week, eventually managing to establish a flourishing restaurant business. After spending some time in Michigan, he settled in New Orleans (1919), joining a number of other Gees from the same village. With loans from friends and business associates in the Chinese community, he invested $500 (equivalent to about $7,500 today) in a restaurant large enough to accommodate several hundred patrons and an eight-piece orchestra, in time emerging as a local leader and advocate for Chinese interests in the city.

Harry Gee Sr. felt that any place with an oil industry would be conducive to supporting a restaurant, and so opened a number of restaurants in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and Pampa, Texas. Ultimately, he decided that Houston was a good city in which to put down roots. He urged not only the Gees, but also a number of other Chinese families, to come to Houston, opening up his home to them. As a result, the Joes and the Wongs came from Arkansas and Mississippi at his behest.[64] Harry opened his first restaurant in Houston, the China Clipper, in the 1930s. Located on Milam Street, it eventually closed due to union picketing.

Around the year 1937, he was summoned back to China by his mother in order to marry and continue the Gee family line. During his brief stay there, he married Mar Siu Wah and fathered his only son, Harry Gee Jr. Having fulfilled his filial duties and leaving his wife behind, Harry Sr. returned to Houston and opened more restaurants. The revived China Clipper went on to become one of the largest Chinese eateries in Houston, and the 1952 Dun & Bradstreet Credit Report gave the restaurant an “A1” rating. At the time, it was bringing in an estimated $500,000 in annual revenue.[65] At the China Clipper and at his other restaurants, Harry Sr. provided jobs for his cousins and even for others who were not related by blood, but who bore the same last name or came from the same area of China. Like the Chu brothers, he used family, personal and area-based guanxi to excellent advantage, not only for recruiting purposes, but also as a means of assuring the loyalty and reliability of his employees.

Flyer for Chinese Village

Harry Sr.’s next restaurant, the Chinese Village, was the prototype of a concept restaurant when it opened in the early 1940s. It was one of the few drive-in restaurants in the country, and it employed non-Chinese female carhops clad in short-skirted uniforms. But the enterprise itself was once again a family business. Gordon’s brother Albert was the manager and his other brother Wallace oversaw the kitchen staff. Albert in turn hired his future wife, Jane Eng, as a cashier. George Gee, who moved his entire family to Houston from Arkansas, translated the food orders for the Chinese staff and prepared the trays for the waitresses. Frank Gee, another cousin, worked in the kitchen.[66] At the Chinese Village, the menu comprised mainly of inexpensive American comfort food, fried chicken steak, meat loaf and fried chicken. The restaurant’s fortunes declined when gas rationing was introduced during WWII, but, undaunted, Harry Sr. opened two more restaurants––the China Star and Sun Deluxe––at which he again employed family members, including his daughters, Mayling and Marymay and his son, Harry Jr. Harry Sr. was so successful that he was able to move his family into a two-story house on W. Dallas, a considerable achievement for a Chinese immigrant at the time.[67] His subsequent home on Crawford Street later became a boarding house that rented rooms to Chinese war veterans, some of whom were also members of the Gee family.[68]

With the growth of the Chinese population in Houston during the 1940s, two overseas Chinese organizations were established to serve the interests of local business people––the On Leong Merchants Association and the Hip Sing Merchants Association. Of the two, the On Leong association became by far the most influential. As a reflection of his status in the Chinese community, Harry Sr. was elected president of this organization, a position he held for fifteen years. In the 1940s and 1950s the On Leong Merchants Association seems to have been the center for most social activities involving Houston’s Chinese community.[69] It was an all-inclusive, multi-purpose organization that not only catered to local business interests and city politicians, but also hosted social events, such as dance parties. In addition, the On Leong building became the venue for a certain amount of illicit gambling, the extent of which is unclear. The Houston On Leong association was investigated but never charged by the FBI when the Bureau brought gambling and racketeering charges against the Chicago On Leong chapter in 1991.[70]

By 1952, Harry Sr. had helped raise enough money for a new building for the On Leong association on Chartres Street. The complex also housed Harry’s Sun Deluxe Café, and was only a few blocks away from the Chinese Baptist Church in Houston. Further down the street was the headquarters of the Houston chapter of the Chinese American Citizen’s Alliance (CACA), a local branch of a nationwide civic organization.[71] In the 1940s, the Chinese Baptist Church sponsored a Chinese language program in the summer for Chinese children, but it was not nearly as involved in the lives of the Chinese community as the On Leong association or the CACA.[72] As the younger generation of Chinese in Houston came of age in the late 50s, the CACA began to take over the activities of the On Leong. At the same time, family associations began usurping the social roles of the On Leong association, holding their own New Year celebrations and organizing their own annual picnics.

When Harry Sr. retired, his wife, Mar Siu Wah, and one of his daughters went to work for their cousin and former manager, Albert Gee, in the latter’s Polyasian Restaurant. However, none of Harry Sr.’s children continued in the restaurant business. Their stories seem to fit a pattern of migrant assimilation outlined by the sociologist Milton Gordon in the 1950s. According to Gordon, there are seven stages through which newcomers in a given society can become “fully integrated” into the mainstream society. The first is cultural: immigrants self-consciously adopt the language, dress, and daily customs of the host society. Many also adopt “Western” names. The next step is active engagement with the host environment by joining clubs, churches and other such mainstream social institutions. From this stage, the immigrant may feel a close bond to the host society, an experience Gordon calls “identification assimilation.” Then, there is the phenomenon of intermarriage. The next two rather ambiguous stages, “attitude reception” and “behavior reception,” are marked by a presumed lack of prejudice on the part of both the immigrant and members of the host society. The final step, “civic assimilation,” suggests the obliteration of power differentials between the immigrant and the host culture.[73] Understandably, Gordon is not sure whether the final three stages can ever be fully achieved, but we can see examples of the first four in later generations of the Gee family.

Harry’s son, Harry Jr., was born in Kaiping, coming to Houston with his mother at the age of two-and-a-half. By then, Harry Sr. had already established a solid restaurant business. Harry Jr. worked in his father’s restaurant throughout his high school years, graduating from Rice University, and then from the University of Texas’ law school. As we will discuss below in somewhat greater detail, he is now one of Houston’s most prominent immigration attorneys and has an interracial marriage (Texas repealed its anti-miscegenation law in 1967). All three of Harry’s children attended Rice; two are attorneys and his son works in his father’s law firm. Each is married to a non-Chinese person. As for Harry Sr.’s two daughters, Mayling worked as a school teacher while Marymay manages her brother, Harry Jr.’s law firm. Both married Chinese men.

The Gee Brothers: Reaching Beyond the Chinese American Community

The Gee brothers Albert, Wallace and Gordon, whose grandfather was the brother of Harry Sr.’s father, were all beneficiaries of Harry Sr.’s mentoring. When their father died and they lost the family business, their widowed mother brought them home to China. But before long, she sent them back to the States, one at a time. Albert returned to San Francisco when he was eleven, and when Harry Sr. moved to Houston in 1936, he sent for Albert. Harry Sr. put Albert to work in two of his restaurants. Albert then brought his younger brothers to Houston, soon opening two of his own restaurants, Gee’s Kitchen and the Frying Pan. He married Jane Eng from San Antonio, after which the latter dropped out of Rice University and went to work as a cashier in Albert’s restaurant. Albert went on to establish some of the most popular Chinese restaurants in Houston. He created the Hong Kong Chef, the Chinese Oven, Ding How, the Polyasian, and the Polyasian West. His last restaurant was Albert Gee’s Cuisine of China, where he was credited with having introduced Cantonese haute cuisine to Houston. He brought glamour, fun and exoticism to Chinese restaurants by combining Chinese, Japanese and Polynesian cooking styles, all in the same eatery, and also popularized the concept of the Chinese takeout in two of his restaurants.[74]

Albert Gee in the Houston Chronicle

Outgoing, well-spoken, and entrepreneurial, Albert and his two brothers created a web of political and social connections for the Gees through their restaurants. When the mayor and city council members came to dine, the brothers either discounted the meal or served them free of charge. They did not charge policemen for coffee, because the sight of a parked police cruiser served as a great crime deterrent. Wallace eventually opened a cafeteria within the headquarters of the Houston police.

Albert’s Polyasian restaurant was situated next to the Shamrock Hotel, a hotspot for visiting celebrities and entertainers. The Houston Chronicle’s society columnists, Bill Roberts and Maxine Messinger, would frequently bring celebrities to lunch, and Albert never charged them. Albert was photographed with movie stars such as Bob Hope, Dale Evans, Will Rogers and news anchor Connie Chung, and appeared in the food section of the Houston Chronicle as the local authority on Chinese cuisine. When President Richard Nixon came to visit Texas, Albert and Jane were invited to Governor John Connally’s ranch, and they attended a White House function as well. After Albert passed away in 1978, Gordon’s restaurant became the gathering place for the mayor and city politicians. As a result, Gordon became something of a kingmaker in Houston city politics.[75]

For Houston, Albert Gee left an enduring legacy for the city he loved. Perhaps his most important role was in desegregating Houston restaurants when he served as president of the Houston Restaurant Association in 1961–2. This remarkable feat came about in part due to Albert’s good relationship with Julius Carter, the publisher of the Forward Times and a prominent leader of Houston’s African American community. Together, they achieved the peaceful and orderly integration of the city’s restaurants at a precarious time when desegregation was leading to urban racial tensions in many parts of the country.[76] Albert was also founder and president of the Houston Lodge of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, which, as mentioned above, was an organization that supplanted the On Leong Association in serving a younger generation of immigrants (see also below). He soon rose to become the first person outside the state of California to serve as CACA’s National Grand President. When he died, Mayor Jim McConn and the city council passed a resolution praising Albert as a “civic leader . . . [and] mayor of the Chinese community,” a person “whose warmth and principles were always exerted (..) [for] the advancement and refinement of the entire Houston community.”[77] All three Gee brothers, through a combination of hard work, entrepreneurial acumen, effective networking and political astuteness, were able to elevate the social, political and civic stature of Chinese Americans in Houston, even during the Jim Crow era.

Richard and Pat Nixon, John and Nellie Connally, Albert and Jane Gee

The Gee Women: Between Worlds and Beyond Stereotypes

Without their wives working alongside them, the Gee males would probably not have been as successful as they were. And the Gee women, for their part, may not have had the same degree of social and economic success without the opportunities afforded by their own employment. Unlike their prescribed roles in their countries of origin, women who have migrated to other countries often contribute to the financial welfare of the family, in so doing gaining economic power. Their enhanced power, in turn, often causes a shift in the family dynamics, one that accords them more freedom and authority.[78] In the case of the Gee women, they were able to gain increased agency as they assumed equal roles with their husbands in their business partnerships on the one hand by operating cash registers, managing stores, and directing their children to help out, while on the other hand assuming primary responsibility for establishing the cultural parameters of the family. They spoke Chinese to their children and observed some Chinese cultural traditions (such as celebration of the lunar New Year), but they served American as well as Chinese food at home. They urged their children to learn Western ways at school (while maintaining the traditional Chinese emphasis on high academic achievement), and encouraged them to attend the Chinese Baptist Church, which offered English lessons and a glimpse into Western ways of living. Their strategy held their families together in the face of economic hardship, racial discrimination and the difficult process of adjusting to a new set of religious, social and cultural values.

For the Gee women, direct involvement in the family’s economic activities opened the door to ever wider contacts and ever greater opportunities. The following stories are about three Gee women who shaped their lives in ways that enabled them to make significant contributions, not only to Houston’s Chinese American population, but also to the city of Houston as a whole and the state of Texas as well.

Jane Eng Gee

Albert Gee’s future wife, Jane Eng, grew up working in the family store during the early 1920s. She was one of seven siblings who lived together above the store in a Hispanic neighborhood of San Antonio. Her parents placed great emphasis on education, and Jane was able to attend Rice University as a pre-med major in 1940. As it happened, she met Albert Gee, fell in love and dropped out of Rice to marry him. Although she regretted never finishing her degree, Jane found great satisfaction in managing Gee family enterprises and contributing to the civic life of Houston. She claimed that her work ethic was shaped by her grandfather, who used to admonish his grandchildren at the dinner table: “If you don’t work hard and save your money, you won’t even have watermelon peel to eat someday!” And that, “scared the heck out of me,” said Jane.[79] After their marriage, Jane ran Albert’s grocery store and takeout restaurant while raising their daughters, Janita and Linda.

When Albert became president of the CACA, Jane helped him write many speeches. She, herself, was elected president of the Women’s Auxiliary of the CACA. The organization encouraged voter registration among the Chinese, and also helped Chinese grocery storeowners obtain their health cards––a state requirement for operators of food-related establishments. Four years after Albert’s passing, Jane became the first woman president of the CACA. She was also asked to chair the Miss Chinatown pageant, which had begun informally in the 1960s. Jane agreed on the condition that she had full rein in running the event. Laughingly, she admitted, “I was a pretty tough cookie in those days!”[80]

Jane chaired the Miss Chinatown Pageant for fifteen years before passing the baton to her daughter, Linda Wu. Jane laid the groundwork for the pageant by lining up sponsors and advertisers. She found contestants by approaching young ladies at Chinese community events and prevailed upon a friend, Cookie Joe, to donate her time training the contestants to sing and dance. The pageant offered young women the opportunity not only to earn a scholarship, but also to receive lessons in grooming and social etiquette––another form of cultural assimilation. After Albert died, Jane sold the restaurant business and turned to real estate. She founded the Jane Gee Realty Company, counting many restaurant and grocery store colleagues among her clients. When she turned 65, she took up competitive ballroom dancing, and was once judged by the movie star Juliet Prowse.[81] Through a process of radical reinvention, and yet without completely abandoning her cultural heritage, Jane Eng became, in every sense of the word, a model for Houston’s Chinese-American community.

Martha Jee Wong

Martha Jee Wong’s family (Jee is an alternative transliteration of the same Chinese surname, Gee) hailed from Kaiping county. Her parents initially settled in Ruleville, Mississippi, but later moved to Houston so that their children could attend a segregated “white” school.[82] Although Asians were able to go to school with white children in Texas, they were not allowed to buy property in white neighborhoods, nor to find employment in most “white” professions. Consequently, Martha lived as a renter in the back of a store in a blue-collar white neighborhood. Later, however, Martha’s father persuaded a loyal customer to buy a house for him. Her dad served as president of the On Leong Merchant Association and the Gee Family Association, as well as a volunteer air raid warden for his neighborhood. So seriously did he take his civic responsibility that he would close down his store, a rare occurrence, to cast his vote—an act that left a deep and lasting impression on young Martha.

At the University of Texas, Martha joined an all-white sorority and was elected president in the following year. She later attempted to integrate the sorority but was unsuccessful. Upon graduation, she held a succession of jobs as a teacher, a school administrator, an associate superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, a professor at Baylor University, and an administrator in Houston’s Community College system. A chance opportunity allowed Martha to run as the first Asian American woman on the Houston City Council, and she won the run-off by tapping into her vast network of local support. Later, Martha was elected as the first Asian American woman in the Texas State House of Representatives, ironically representing those same districts that had previously denied residency to Asians. In addition to being a trailblazer for Asian Americans in politics, she co-founded the Asian American Coalition, became deeply involved with the Asian/Pacific American Heritage Association, and served as the first female president of the Gee Family Association.

In a 2011 HAAA interview, Martha underscored the importance of guanxi to her distinguished career: “Relationships,” she said, “are so important, in everything that you do.” She pointed out that personal connections were crucial, not only for getting the jobs that she did, but also for the politics she engaged in and the money she raised for political purposes. She went on to say: “The more that you include people, the bigger your network becomes, and then they will introduce you to somebody else, and then you’ve another whole new network.” Her advice, then, for becoming a leader in any organization or enterprise was first to demonstrate leadership qualities and then, “when you get ready to run,” you have “all these people to call upon” for help.[83]

Rogene Gee Calvert

Rogene Gee Calvert’s father, David Sep Yeul Gee, was one of the Gee cousins who learned the grocery trade under C.Y. Chu’s tutelage at the Jun Yick (later renamed Asia Food Market). His store was located in Houston’s Third Ward, a predominantly African-American neighborhood. He came to the United States illegally as a “paper son,” using the last name of Hom. Like many such individuals, he lived in perpetual fear, not of arrest by U.S. law enforcement officers, but of blackmail on the part of Chinese criminals. After a general amnesty for “paper” sons and daughters was declared in 1961, Rogene’s father became a U.S. citizen and recovered his real last name of Gee. Eventually, the entire family did the same. According to Rogene, in her early days, relations between the Chinese and the African-Americans were relatively peaceful, but as the neighborhood deteriorated, the store was held up many times. Eventually, Rogene’s family sold the store to Vietnamese buyers, who in turn sold it to Middle Easterners. Profits for such mom-and-pop stores amounted to between $30,000 and $50,000 annually if family members staffed the store and worked for free.

Graduating from UT with a degree in political science, Rogene has spent most of her career in non-profit organizations, public policy groups and local politics. In her travels, she discovered that cities smaller than Houston already had community and health care centers for Asians, so Rogene co-founded the Asian American Family Counseling Services (later known as the Asian American Family Services) and the Asian American Health Coalition, which established the community health center HOPE Clinic several years later. Houston’s HOPE Clinic has since grown into a federally-funded multi-million-dollar operation. Rogene also co-founded the Houston chapter of the 80-20 Political Action Committee and has been active in the Organization of Community Advocates (formerly known as the Organization of Chinese Americans), both of which promote Asian American interests.[84] Rogene has received many awards and honors for her community leadership, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Award for Health Equity for 2017. She says of her selfless dedication to good causes: “I like to solve problems, connect resources with needs and make things happen. So, if it materializes in an agency, then that is good. But, I’ve also found that the best legacy is that it continues after you’re gone so that it isn’t about you.”[85]

Other Trajectories, Different Stories

In this final section, we briefly explore the lives of a few additional male Gee family members who, like the Gee women discussed immediately above, began their lives in difficult circumstances, but went on to distinguish themselves in areas that were sometimes far removed from their roots. All benefitted directly from the patronage of Harry Gee Sr., and all experienced some form of prejudice, but each valued education and each carved out a significant niche in the larger professional world. Most importantly for our purposes, all of them did their best to give something back to the Chinese American community from which they came or to which they moved. This is one of the most significant themes to emerge from our analysis of the Gee family history.

In Sakowitz Drawing Cubicle, Beck Gee Self-Portrait

Beck Gee

Beck Gee, born in China in 1922, arrived with a “paper brother” and spent thirty days alone on Angel Island.[86] His parents sent him to study in the United States and to live with his grandparents, who were already in Mississippi. Barred from attending public school with white students once he reached the age of thirteen, Beck worked in the family grocery store for the next seven years. During World War II, he was drafted into the U.S. Air Force, serving as a photographer in the Air Corps and meeting his wife during his tour in England. After his discharge, Beck and his wife opened a grocery store in Houston, which operated for nine years. During that time, he obtained a Bachelor of Applied Art from the University of Houston and was subsequently hired by the Sakowitz department store to work in their advertising department. For the next thirty-one years, he designed and produced newspaper advertisements for various department stores in Houston. Looking back on his life, he wondered what his life might have been like if he had gotten a “regular education” in Mississippi. “I might have been some kind of engineer,” he mused.”[87] The people of Mississippi, he opined, “were not bad.” The problem was “just the laws.” Beck served as president of the Gee Family Association for one year and set up a scholarship in his name and in the name of his deceased wife and son. He was a charter member of the Chinese Professional Club, and he was also involved with CACA.

Henry Gee

Henry Gee’s grandfather was a railroad worker on the transcontinental railroad, and he obtained his papers after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[88] Henry was born in China and brought to live in Mississippi at the age of sixteen. Because he could not attend school with white students, Henry was invited to Houston by Harry Gee Sr. The two were only distantly related, “maybe six or seven generations back,”[89] but the tie was strong enough. Henry worked in Harry’s Chinese Village restaurant and lived in the quarters behind the restaurant. After high school, he joined the Navy, where the only racial incident he recalls was when a barber refused to cut his hair. Upon discharge, he attended the University of Texas in Austin on the GI Bill. Because of his status as a war veteran, Henry was hired by the Texas Highway Department, circumventing the discriminatory hiring practices that were prevalent at the time. He pursued his career as an engineer and retired at age sixty-five. With a group of friends, Henry started the first Chinese school in Houston, called the Institute of Chinese Culture, which operated out of borrowed classrooms at Rice University for the first eighteen years of its existence.

George Gee

Growing up in Arkansas, George Gee remembered being called names, barred from places that proclaimed “Whites Only,” and finding it necessary to wear a badge stating “I am Chinese,” in order to distinguish himself from the Japanese after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. As with Henry Gee, George’s father, Yum Gee, moved his entire family of twelve children to Houston at the invitation of Harry Gee Sr. in search of a more favorable working environment. Yum had lent money to Harry Sr., and Harry, in turn, hired George and his siblings to work in his restaurant, the Chinese Village. Soon George’s family opened several grocery stores, and eventually George attended the University of Houston on a scholarship. George tried his hand at various ventures, such as the snow cone business and the import trade, but none of them succeeded. Between jobs, he worked as manager of Albert Gee’s Polyasian restaurant. George later became chairman of the United Food Stores, a coalition made up of three hundred Chinese grocery stores. He did the advertising for the group and found his calling when he sold insurance to them.

After selling insurance for eighteen years, George founded his own insurance agency and became the first to hire Asian women as insurance agents. He was perspicacious in realizing that Asian women, who were proficient in different dialects of Chinese, could sell insurance to the Asian community and “opened the door to another thirty million potential [clients].”[90] Many of George’s customers were members of the Chinese mission at the First Baptist Church, where George served as the Chinese Sunday School Superintendent. George was one of the founders of the Chinese Baptist Church, as well as a founding member of the CACA. He served as chairman of the board of the Chinese Community Center, as well as a member of the Chinese Professional Club, and in 2004, was awarded the AARP Voice of Civil Rights Award.

Harry Gee Jr.

As previously mentioned, Harry Gee Jr., son of Harry Gee Sr., worked forty hours a week in his father’s restaurants from the age of thirteen until he left Houston to attend the University of Texas Law School after graduating from Rice in 1960. Four months after graduating from law school, Harry obtained a job in the state Attorney-General’s Office through a cousin’s political connections. He said that the only time he felt discrimination was in East Texas, where he was not welcomed, despite his role as a representative of the Attorney-General’s Office, and where people bluntly asked him what he was doing there, and if he was in the right place.[91] Following this stint, in 1966, Harry found that he could not find a job with any of Houston’s large law firms: no one was hiring any minorities – Asians, Hispanics, African-Americans, Jews, or women.[92] He sent out thirty applications, but received no responses. So he opened his own practice and today remains one of the most successful immigration lawyers in town.

Harry has long seen his profession as a kind of community service, inspired by his father’s example. As was the case with his father, Harry always wanted to make sure that “the people in the community would be well treated and get a fair break.” A legal career, especially in immigration law, would give him “the opportunity to go ahead and do that.”[93] In his effort to raise the visibility of Asian Americans, Harry was instrumental in the formation of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and served as its president. This organization now numbers over fifteen thousand attorneys. Harry was the first Asian elected to the Board of Directors of the State of Texas Bar Association and the first individual belonging to a “minority” group to receive the Leon Jaworski Award for Community Service from the Houston Bar Auxiliary.

Concluding Remarks

What can the story of the Gee family tell us about the more general patterns of Chinese American migration to the United States? In some important ways, the experiences of the Gees conform closely to generalizations made by scholars of Chinese American migration in the past. The two perspectives on the same phenomenon are thus mutually reinforcing. Based on academic studies of traditional Chinese culture and our own investigation of the Gee family, for example, it is clear that certain “Confucian” values and institutions helped to shape the early history of the Gees in America. We see, for instance, an emphasis on diligence, education, loyalty to family and friends, frugality, and self-sacrifice in multiple generations of the Gees. We can also detect a deep appreciation for, and a systematic exploitation of, personal relationships (guanxi), whether based on “family” (blood ties, fictive blood ties and marriage), or linkages based on shared surnames, shared backgrounds, and shared places of origin. In later generations of Chinese Americans, including the Gees, we can surmise that some points of affinity with traditional Chinese culture may have become attenuated. For instance, institutionalized guanxi may not be viewed as important to the collective well-being of Chinese American communities as these communities become more well off and more closely connected to non-Chinese networks. This topic deserves more systematic study.

The history of the Gee family also tells us something about the general patterns and processes of Chinese American assimilation. For instance, the progressive integration of the Gees into the Houston community over time seems to reflect at least some of the stages of assimilation outlined by Milton Gordon. Further research would certainly reveal other ways in which the Gee family self-consciously aligned itself with American culture. At the same time, such research might tell us more about the specific features of traditional Chinese culture that the Gee family continues to celebrate and why. There is much still to be learned.

The Gee story suggests the family’s effective application of “ethnic capital,” which took several forms. One was, of course, access to opportunities for employment and advancement that were based at least in part on ethnic identity and personal connections. Another was the cultural expectation of high levels of obligation and trustworthiness within Chinese American social and economic networks. Yet another, itself a product of bicultural education, was the ability on the part of many Gees to communicate in both English and Chinese. Also, by the latter half of the twentieth century, Chinese entrepreneurs had overcome earlier negative stereotypes, and established a reputation for honesty, integrity and intelligence. Reputation can be a powerful form of ethnic capital.

Finally, we see in the history of the Gees evidence of the way in which their particular experiences in America and elsewhere reflect what McKeown refers to “larger global trends and transnational activities,” and various kinds of “diasporic networks.” Overseas migration is, by definition, a transnational phenomenon, but there is more to the matter than this. At various times, international channels of communication and travel were more open or less open, depending on variables such as war and peace, and the domestic policies of individual nation-states. The Gees made all kinds of strategic and tactical choices based on their perception of relative advantage in the global marketplace. None of them had to go to America, especially in the late nineteenth century, when, after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the environment was in many ways extremely unfavorable to Chinese interests. And yet they came. In terms of more personal choices, Harry Gee Jr. married a woman of German descent and Beck Gee met his future wife in England. All three of Harry Gee Jr.’s children married non-Chinese, bringing significantly different personal experiences and cultural influences into the family mix. And we know that in a few cases, Gee children in America were shipped back to China, only to return to the States under different circumstances. Moreover, at least two Gee family members saw duty in the U.S. military. One member of the Gee family tried his hand at international trade, and we can assume that closer investigation of other Gee business ventures might well reveal other instances of transnational interactions.

But our brief discussion of the Gee family raises as many questions as it answers. Beyond the generalizations offered above, how typical were the experiences of the Gees in their particulars? Are there, or have there been in the past, Chinese American families in Houston that faced challenges and opportunities similar to the Gees, but who did not do as well? Why? Are there other success stories in Houston that follow a different trajectory? What about Chinese American families like the Gees in different parts of the country? How similar and how different were their experiences? From a transnational perspective, why did the Gees choose America over other destinations? From an “ethnic capital” standpoint, how, when and why did the early Gees learn English? We may also ask other kinds of questions, such as whether the Gees fit Wang Gungwu’s conception of “sojourners”?

The Gee family story also opens up all sorts of cross-cultural comparative questions. To take just one of many examples, it is often asserted that, on the whole, Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants are far more successful than other Asian immigrants in American schools. Some authorities claim that a crucial variable in the equation is the “Confucian” heritage of both cultures (which is absent in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar).[94] There may well be something to this thesis, but it needs to be more rigorously tested. How do we do this? A productive start in this direction would be to develop more interview-based case studies of the sort that the HAAA project encourages.

APPENDIX: Edward C.M. Chen

One additional Gee family member deserves mention here: Edward C.M Chen, related to the Gees by marriage. Although his background and career are unlike those of the other Gee family members we have discussed, Ed played a pivotal in documenting the lives and times of Chinese-Americans in Houston.[95]

Ed was one of the earliest Chinese born in Houston. He attended Rice University, and upon graduation worked in the petroleum industry and in NASA’s space program. He became a professor of chemistry at the University of Houston, Clear Lake, and has published over one hundred scientific papers.[96] On his own volition, Ed researched the early arrival of Chinese in Houston, and wrote a column on the subject in the Southwest Chinese Journal titled “The Golden Mountain on the Gulf.”[97] He also penned an unpublished booklet titled “Into the Future Together: 136 Years of Progress, 1862-1998,” which contains extremely valuable information on the early settlement of Chinese in Texas. Ed gained permission from the Texas Historical Commission to establish a historical plaque commemorating his father, Ed K. T. Chen (henceforth K.T.), who saved the Chinese American community in Texas from possible internment during the Korean War.

K.T. was born in San Francisco and attended Columbia University in 1928. Upon graduation, he worked for a Chinese newspaper and, in 1932, he became secretary to the Vice Consul for the Republic of China in Galveston. In 1937, he and Mrs. Rose Wu of San Antonio lobbied to defeat a Texas land bill that would have prevented Chinese from owning land in Texas. K.T. became a professor of languages and political science at the University of Houston. He also taught Chinese to FBI agents, and translated FBI intelligence information from Communist China. During the McCarthy era, in order to prevent Chinese from being interned, he volunteered to find the Chinese American Communist sympathizers in the community, who were subsequently deported to China. He wrote a white paper for the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover that helped identify many Communist sympathizers in the U.S.[98] K. T. was the founding president of the Houston lodge of the CACA. He adroitly used his elite status, that of a diplomat and an intellectual, to improve the well-being of the Chinese Americans in Houston in the days of Jim Crow.

[1] Graziano Battistella, “ Migration in Asia: In Search of a Theoretical Framework, “ Ch. 1, in Global and Asian Perspectives on International Migration (Cham: Springer, 2014), 1. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.rice.edu/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-08317-9, accessed Oct. 6, 2018.

[2] Everett S. Lee, “A Theory of Migration,” Demography, 3:1 (1966): 47-57 and Guido Dorigo and Waldo Tobler, “Push-Pull Migration Laws,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 73.1 (March 1983): 1–17.

[3] Battistella, 2. See the special issue on migration in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36:10 (2010): 1531-1711.

[4] See Jianli Huang, “Conceptualizing Chinese Migration and Chinese Overseas: The Contribution of Wang Gungwu,” Journal of Chinese Overseas, 6 (2010): 1–21.

[5] For a “classic” but sharply debated definition of the term, see Paul C. P. Siu, “The Sojourner,” American Journal of Sociology 58.1 (July,1952): 34–44. Siu considers the “essential characteristic” of a sojourner to be an attachment to “his own ethnic group” rather than a more “bicultural” orientation. The sojourner, he claims, is an immigrant who “clings to the culture of his own group” and is unwilling to organize himself as a permanent resident in the country of his sojourn.” Siu, 34. Cf. Philip Q. Yang, “The ‘Sojourner Hypothesis’ Revisited,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 9.2 (Fall 2000): 235–58.

[6] Jianli Huang, 10. Cf. the discussion of “diasporic nationalism” in Adam McKeown, “Conceptualizing Chinese Diasporas, 1842 to 1949,” in Hong Liu, ed., The Chinese Overseas, Vol. 1 of 4: Conceptualizing and Historicizing Chinese International Migration (London: Routledge, 2006), Ch. 4, 98-136.

[7] For another more broadly-based diachronic overview, see Guohong Zhu, “A Historical Demography of Chinese Migration,” in Hong Liu, ed., The Chinese Overseas, Vol. 1 of 4: Conceptualizing and Historicizing Chinese International Migration (London: Routledge, 2006), 143–144.

[8] See Philip Q. Yang, “The ‘Sojourner Hypothesis’ Revisited,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 9.2 (Fall 2000): 235–58.

[9] Leo Suryadinata. Understanding the Ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007): 65–68.

[10] McKeown, 105.

[11] Kyeyoung Park, “A Rhizomatic Diaspora: Transnational Passage and the Sense of Place Among Koreans in Latin America,” Urban Anthropology, 43:4 (2014), 481.

[12] McKeown, 99.

[13] McKeown, 101.

[14] McKeown, 114.

[15] McKeown, 115.

[16] McKeown, 100.

[17] McKeown, 105.

[18] Guohong Zhu, Ch. 5 “A Historical Demography of Chinese Migration” in Hong Liu, ed., The Chinese Overseas, Vol. 1, 157.

[19] Peter Kwong and Dusanka Miscevic, Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Community (New York: The New Press, 2005), 6; Monique Avakian, Atlas of Asian-American History (New York: Facts on File Inc., 2002), 27.

[20] For an illuminating discussion of Chinese employment patterns from the early 1870s to the early 1970s, see Haitung King and Frances B. Locke, “Chinese in the United States: A Century of Occupational Transition,” The International Migration Review, 14.1 (Spring, 1980): 15–42.

[21] For a useful summary, see National Archives, “Chinese Immigration and the Chinese in the United States,” no pagination. URL: https://www.archives.gov/research/chinese-americans/guide, accessed 9/26/2018.

[22] Library of Congress, “Chinese Immigration,” no pagination. URL: https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/chinese9.html, accessed 10/6/2018.

[23] For an in-depth look at the legal treatment of the early Chinese immigrants , see Gilbert Thomas Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law (New York: AMS Press, 1969), Angelo N. Ancheta, Race Rights and the Asian American Experience (New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 1998), Charles T. McClain, Jr. “The Chinese Struggle for Civil Rights in Nineteenth Century America: The First Phase, 1850-1870,” California Law Review, 41:3 (Sep. 2007), Paul Finkelman ed., Milestone Documents in American History: Exploring the Primary Sources that Shaped America (Dallas: Schlager Group Inc., 2008, and Paul Finkelman, Controversies in Constitutional Law: Collections of Documents and Articles on Major Questions of American Law (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2001).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Thomas Gold, Doug Guthrie, and David Wang, eds., Social Connections in China: Institutions, Culture, and the Changing Nature of Guanxi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 7. See also Ambrose Yeo-chi King, “Kuan-hsi and Network Building: A Sociological Interpretation,” Daedulus, 120:2 (Spring, 1991), 70.

[26] For historical background on guanxi, see Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture (Lanham, MD., New York and London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), 120–21.

[27] Avakian, 101–2.

[28] “Chinese American Citizens Alliance” URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_American_Citizens_Alliance accessed 3/3/2018. See also “Chinese American Citizens Alliance” http://www.cacanational.org/htmlPages/history.html, accessed 9/26/2018.

[29] See National Archives, “Chinese Immigration and the Chinese in the United States,” no pagination. URL: https://www.archives.gov/research/chinese-americans/guide, accessed 9/26/2018.

[30] Edgar Wickberg, “Overseas Chinese Adaptive Organization, Past and Present.” Ch. 23, in Hong Liu, ed., The Chinese Overseas, Vol. 2 of 4: Culture, Institutions and Networks, 87–103. Adam McKeown, 115, notes that these organizations also allowed members to maintain contact with their home villages and towns, and enabled them to have “their bones shipped back after they died.”

[31] Organizations of this sort, known in Chinese as huiguan (native-place guild halls), had powerful antecedents in traditional China from the Ming dynasty onward. See Smith, The Qing Dynasty, 165–66.

[32] These clandestine organizations had their antecedents in the secret societies of Chinese tradition. See Smith, The Qing Dynasty, 167–68. Tongs did not always engage in illegal activities, however.

[33] H. Mark Lai, “Historical Development of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association/Huiguan System” 13–50. The Him Mark Lai Digital Archive, Chinese Historical Society of America. URL: https://himmarklai.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Historical-Development-of-the-Chinese-Consolidated-Benevolent-Association.pdf?9388f2, accessed 9/26/2018.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Wickberg, 92.

[36] Wickberg, 91.

[37] See Jianli Huang, “Conceptualizing Chinese Migration and Chinese Overseas,” 1–21.

[38] Of the thirteen thousand or so Chinese American soldiers who served during the war, almost half were not U.S. citizens, still barred by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Library of Congress, “Chinese Immigration,” no pagination.