Pierre Berton: You’ve lost me!

Bruce Lee: [laughs] I have, huh? …I mean here is the natural instinct, and here is control. You are to combine the two in harmony. Not—if you have one to the extreme, you’ll be very unscientific. If you have another to the extreme, you become all-of-a-sudden a mechanical man—no longer a human being.

[…]

Pierre Berton: Do you still think of yourself Chinese, or do you ever think of yourself as North American?

Bruce Lee: You know what I want to think of myself? As a human being. Because—I mean, I don’t wanna sound like, “as Confucius, sayyy....”—but under the sky, under the heaven, man, there is but one family. It just so happens, man, that people are different.

— Interview on The Pierre Berton Show, 9 December 1971[1]

Bruce Lee did not set out to be a hero; he wanted to be an actor, a human being of action. Basically, he wished to be somebody: a human being who genuinely expressed himself in the kinetic language of martial arts, and one who helped others, likewise, to express themselves. And yet, despite his untimely death in 1973 at the age of 32, Bruce Lee posthumously became an international hero, a person who exerted a profound influence on global culture, providing a transcultural model of what it means to be truly human. With his lightning-fast kicks, incredible physique, and almost universally-recognizable kung fu battle cry (“Whoooeeeaaaaah!!!”, variously spelled), Bruce Lee became not just somebody, but rather the body that transformed Asian and American cinema: martial arts, body expression, fitness, masculinity, race, class, and anticolonialism. Mette Hjort wrote that “The transnational is prompted by economic necessities but the overarching goal is to promote values other than the purely economic: the social value of community, belonging, and heritage…and the social value of solidarity in the case of affinitive and milieu-building transnationalism.”[2] Bruce Lee embodied those values and inspired millions around the world of all ages and ethnicities. He was, I would argue, not only the first truly transnational Asian man of his age, but also a fighter for our age.

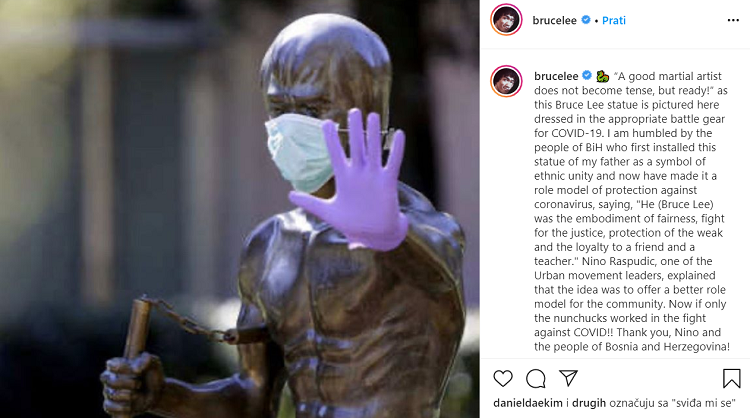

“We will always be Muslims, Serbs, or Croats. But one thing we all have in common is Bruce Lee,” said Veselin Gatalo of Urban Movement Mostar in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a country that was ravaged by civil war and the horrors of attempted genocide in the 1990s. Mostar was a city divided between Catholic Croats and Muslim Bosniaks. After hostilities ended, the people of Mostar chose to erect a peace memorial. Of the nominees, Bruce Lee was chosen even over the Pope and Gandhi, because polls revealed “he was the only person respected by both sides as a symbol of solidarity, justice, and racial harmony.”[3] It was the world’s first Bruce Lee statue. I include a photo of the bronze statue (Figure 1 below; screen-captured from Instagram, 8 April 2020), worth its weight in gold during the current coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic with its noticeable “upgrade,” a thoughtful reminder from the Mostar community that we are all in this together.

Those famous “nunchucks,” plainly visible in Bruce Lee’s right hand, while not exactly medical-grade “personal protective equipment” (PPE), might lift spirits enough to help just a little in fighting the pandemic! Joking aside, however, what does Bruce Lee have to do with coronavirus, cyberpunk, and our collective transnational future?

The year 2020 has been one of widespread economic disruption, sickness, and death. I need only briefly remind readers of the extent of the continuing disaster: in the United States alone, repeated lockdowns, businesses gutted, a peak of forty million jobless claims and a national unemployment rate exceeding fourteen percent, the highest since the Great Depression. At the time of writing (January 2020), American hospitals were overwhelmed, with over twenty-four million cases of infection and over 400,000 deaths having been reported. Globally, the infection toll had exceeded ninety million, while the death toll had passed two-million mark. As numbers continue to rise, the situation is grim. Although currently far less lethal in total mortality than the catastrophic influenza pandemic (commonly referred to as the ‘Spanish Flu’) of 1918-1920, almost exactly a century ago, the coronavirus pandemic has wreaked appalling damage worldwide.[4]

2020, a year that had been “sort of canceled,”[5] and certainly a year of heartbreak, outrage, suicide, street protests, and general despair in America, Asia, and the world, was one of great confusion, fear, hate-mongering, misinformation, and outright lies. The lights on Broadway are out; so are the lights of over 100,000 restaurants, small businesses, schools, and offices across the U.S. Amid this growing compendium of woe, the United States government, led by President Donald Trump, engaged in a trade war and a cyberwar with China, both sides taking actions and manipulating information in ways that have led to serious talk of a new Cold War. Most germane to this essay is the fact that U.S. President Donald Trump chose this moment of crisis to insult Bruce Lee, kung fu, the Chinese, and, by extension, Asian people generally, using much the same strain of mob-rousing racist, xenophobic rhetoric that historically infected America—you guessed it—exactly a century ago.

Calling COVID-19 the “China virus,” the “Chinese virus,” “Wuhan virus” and “kung flu,” Donald Trump loudly and repeatedly blamed China and the Chinese in thinly-disguised racial vitriol for crossing the Pacific bearing the coronavirus. At a political rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma (20 June 2020), he decided to make a “joke” about the deadly pandemic. The “Chinese virus” or coronavirus, he remarked, “has more names than any disease in history. … China sent us the plague . . . [and] I can name [it] ‘kung flu.’” Trump told the audience, “I can name 19 different versions of names,” and the crowd laughed appreciatively.[6] The Asian-American community immediately objected, but Trump uttered the phrase “kung flu” again in Phoenix, Arizona, while his supporters chanted the term as a sort of rallying cry.

Buzz Patterson, a Republican political candidate, supported Trump’s utterance with a shameless rhetorical question: “If ‘kung flu’ is racist, does that make Bruce Lee and ‘kung fu’ movies racist?” This provoked the ire of Bruce Lee’s daughter Shannon Lee, who retorted, “Saying ‘kung flu’ is in some ways similar to someone sticking their fingers in the corners of their eyes and pulling them out to represent an Asian person. It’s a joke at the expense of a culture and of people. It is very much a racist comment...in particular in the context of the times because it is making people unsafe.”[7] Coronavirus-fueled harassment and verbal/physical abuse of Asian-Americans, which were already rising in 2020, were repeatedly stoked by the racist pronouncements of President Trump and many of his followers.[8]

As early as February 2020, a man in New York City hit a woman wearing a face mask, “who appeared to be Asian,” calling her a “diseased bitch,” and in a Los Angeles subway during that same month, a man called the Chinese people “filthy,” claiming that “Every disease has . . . come from China because they’re f****** disgusting.”[9] In March 2020, a near-fatal hate crime took place in Texas, when a man stabbed members of an Asian family (including boys aged two and six, one of whom he wounded in the head) inside a Sam’s Club, believing the family to be Chinese and diseased “carriers” of the coronavirus. Dr. Kevin Nadal, who serves as a national trustee for the Filipino American National Historical Society, said of the incident, “The president’s insistence on referring to COVID-19 as the ‘Chinese Virus’ has emboldened anti-Asian bias. The increase in anti-Asian hate crimes is, without a doubt, a result of the racially charged rhetoric of COVID-19. Words matter.”[10]

A much-acclaimed new documentary on Bruce Lee called “Be Water” (official trailer) was created by Asian-American director Bao Nguyen, airing in June 2020 on the ESPN channel; it could hardly be timelier. Nguyen’s film argues that Bruce Lee is a protest figure whose life and words speak to us directly today in the age of Black Lives Matter—and other movements for racial justice, civil rights, and an end to police brutality—which have exploded onto the streets of America right before our eyes.[11] While the dominant narrative is that Bruce Lee was “this martial arts god, in many ways, and a film icon,” Nguyen stated that he “really wanted to see him through the lens of an immigrant American,” whose life stream coincided with the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s-1970s and the opening of China, and whose life was a constant protest against racism on both sides of the Pacific. “Bruce Lee is not seemingly the prototypical American,” Nguyen said, “But when you dive deeper . . . it’s very much the epitome of an American story.”[12] Nguyen holds that Bruce Lee’s legacy transcends borders, just as his life tied Hong Kong and America together across Pacific waters:

Even though Bruce Lee passed away nearly 50 years ago, his words continue to inspire action against oppression and injustice…protesters in Hong Kong are fighting for their way of life and black protesters in America are literally fighting for their lives—many having adapted Bruce’s ethos in their movement. As he said, “water can flow or it can crash,” and at this moment, our country seems to be crashing against a system and way of thinking that has for too long treated African-Americans as less than human—denying them justice, equity, and tragically, many times their own lives, like in the cases of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, among countless others.[13]

Indeed, Bruce Lee’s life and legacy are prismatic lenses that allow us to reexamine our dynamic, transnational, and troubled times, sometimes in surprising ways. Perhaps most readers of this essay will not be martial artists, film buffs, or cyber-navigators; but Lee’s influence extends far beyond the fields of martial arts and so-called chop-socky films. As Paul Bowman wrote, “Bruce Lee has always been construed as a figure who existed at various crossroads—a kind of chiasmatic figure, into which much was condensed, and displaced. His films…have also been regarded as spanning the borders and bridging the gaps not only between East and West, but also between ‘trivial’ popular culture and ‘politicized’ cultural movements.”[14]

It is high time to reconsider the influence of Bruce Lee on our American collective culture (understood as a synthesis of transnational America and transnational Asia), and especially our street culture. Why? Because Black Lives Matter, and, as Lee recognized presciently, Asian lives and Asian culture can help make black and minority lives matter much more. Bruce Lee was literally––biologically and culturally––a transnational figure. His father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was a traditional Cantonese-opera singer, and his mother, Grace Ho, was the mixed-race descendant of a wealthy Eurasian family whose roots dated back to the history of British colonialism and foreign extraterritoriality. Bruce Lee’s lineage was one of migrants, among countless others in Hong Kong, a polyglot entrepôt of immigrant Chinese, British, Indian, and other peoples from across the British Empire.

Lee was born an American citizen in San Francisco, but his parents took him back to Hong Kong, where he was bullied for being a mixed-race “mongrel.” Thanks to his father, Lee had an early movie career as a child actor in Hong Kong cinema, and he was especially good at playing the part of the brash but charming orphan. However, Lee was a troublemaker and prankster who learned Wing Chun Kung Fu so that he could street-fight. When Lee’s Wing Chun classmates discovered that Lee’s mother was half-European and that he was not, therefore, “pure” Chinese, they shunned him.

In 1959, at the age of eighteen, Lee was kicked out of Hong Kong by his own parents after another bad street fight, and he took the slow boat to America with just $100 in his pocket. He worked as a dishwasher and waiter at Ruby Chow’s restaurant in San Francisco’s Chinatown, had his heart broken by his Chinatown-raised proto-feminist Japanese-American girlfriend Amy Sanbo, and became the first Chinese-American to openly break an unwritten Chinese taboo against teaching “non-Chinese” (in this case an Afro-American) the art of Chinese kung fu. He also dabbled in philosophy classes at the University of Washington, where he fell in love with, courted, and married a Caucasian woman, Linda Emery. (The early life of the young couple was dramatized in the Hollywood film Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story [1993], where, in a famous scene, Linda’s mother Mrs. Emery tells Bruce, “You’re an American citizen. You’re not really an American.”) Linda and Bruce had two children, Brandon and Shannon, before Bruce’s unfortunate death on 20 July 1973 in Hong Kong.

Bruce Lee’s race-breaking, no-nonsense attitude led him to teach Chinese Kung Fu to a Filipino-American (Dan Inosanto), a Japanese-American (Taky Kimura), an African-American (Jesse Glover), and many Caucasian-Americans, including boxer Joe Lewis and Hollywood stars such as Steve McQueen and James Coburn, and others. I mention Jesse Glover because when Bruce Lee died, his widow Linda brought his body back from Hong Kong to be buried in Seattle, the city where he had studied, lived, loved, and fought for respect. I once read to my students, and was also myself deeply moved by, the following line from Matthew Polly’s biography of Bruce Lee, which describes Lee’s private funeral: “As the crowd thinned and the mourners returned to their cars, the last person to remain was Jesse Glover. When the workmen came to fill the grave, Jesse took one of the shovels and shooed them away. It was a uniquely American moment—a black man in a suit with tears running down his face filling a Chinese grave in a white cemetery. Jesse says, ‘It didn’t seem right that Bruce should be covered by strange hands.’”[15]

There—I’ve condensed Bruce Lee’s eventful life into a few paragraphs. I offer now a thought piece on Bruce Lee in the time of coronavirus and cyberpunk. We are fighting both battles on- and off-line. We are becoming cybernetic in our work and learning (almost entirely-machine-based and remote due to the “physical distancing” exigencies of the coronavirus pandemic), and in our culture and communication as well, much of which is mediated by ubiquitous mobile devices, social media, and digital information. Donna Haraway famously argued in her 1991 feminist manifesto that the terms cyber and cyborgs empowered her to fashion an “ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism, and materialism,” which allowed her to reject the bright-line identity markers purporting to separate human from animal, and animal from machine, which are products of a “tradition of racist, male-dominant capitalism.” Haraway declared, “We are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.”[16]

Bruce Lee, if he were alive, would likely understand this kind of world, because he was a fighter with a thirst for novelty and knowledge but a deep aversion to mechanical crutches, shackles, and uncritical rules of form. We confront today a reality in which digital technology, automation, machine-learning, and artificial intelligence have intruded into every sector of our lives. In this essay, I suggest that we adapt Bruce Lee’s methodology and examine our own experiences in order to (as Lee once stated) “take what is useful, and develop [it] from there.”[17] Bruce Lee was a transnational, trans-Pacific, and kinetic human being who offers us lessons for studying our own flawed but fertile society—and hopefully mastering it through instinct, control, and compassion. We do not have to go to the extremes indicated in the epigraph above, choosing to be either “unscientific” or “mechanical” men and women who are no longer human beings. Let us, then, engage with Bruce Lee, a transnational fighter for our times.

Cyberpunk Society in the Midst of Covid-19

What the hell, you are what you are, and self-honesty occupies a definite and vital part in the ever-growing process to become a ‘real’ human being and not a plastic one.

— Bruce Lee[18]

If you had mentioned the terms “cyber” and “cybernetic man” to Bruce Lee, he probably would have laughed, but his laughter would have had a serious edge. He was a person who personally and painfully experimented with what was then cutting-edge and unproven technology, such as by inducing reflexive muscle twitches in himself via electric shock stimulation. He was also an assiduous fitness fanatic who experimented with supplements, vitamin cocktails, and protein shakes long before they became the fashion among athletes and health devotees. Lee relentlessly pursued the perfection and expression of the human body. But Lee did not live long enough to see the personal computer age or the age of “smart phones.” If you called him a “punk,” Lee would likely have smiled, because he was once nothing more than a rowdy street punk (a delinquent student, prankster, and rooftop street brawler) in Hong Kong, who managed to become an iconic cultural rebel in America. But as the epigraph quoted above shows, Bruce Lee understood that instinct and control were warring forces that had to be joined in harmony to make a complete, scientific human being, one who was fluid and dynamic, but certainly not a “mechanical man.”

The term “cyberpunk” was coined by Bruce Bethke in a short science fiction story of the same name in 1980 (published in Amazing Stories in 1983). The piece was about a group of teenage crackers (and tech hackers) with ethical shortcomings. Bethke reflected: “Punk kids with cheap, powerful, portable, personal computers the size of notebooks? Ridiculous!”[19] But what he then “set out to do was to name a character type…a young, technologically facile, ethically vacuous, computer-adept vandal or criminal,”[20] operating in the few remaining free spaces of societies dominated by amoral corporations and surveillance states.

What Bethke and other authors—especially William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, who wrote brilliant works of science fiction in the 1980s and collaborated in the classic alternative-history novel The Difference Engine (1990)—did was to open our culture to the promises and perils of cultural change in the wake of technological changes to our minds and bodies. These works represented, in the words of Sandy Stone, “the supreme literary expression if not of postmodernism, then of late capitalism itself.” They “crystallized a new community…[and] established the grounding for the possibility of a new kind of social interaction.”[21] Time magazine in 1993 used the word “cyberpunk” to define a hedonistic countercultural segment of the computer age. But be not deceived: cyberpunk is not marginal or deviant. Rather, it focuses on the most pressing issue of the present generation: command and control of information that defines human potential.

Problems of public space, privacy, urban surveillance, online tracking, malware, and various feedback loops of the endless streams of data that are mined from us—these form our personalized and varied cyber-realities. As Gareth Branwyn wrote, “The future has imploded onto the present. There was no nuclear Armageddon. There’s too much real estate to lose. The new battlefield is people’s minds. …The world is splintering into a trillion subcultures and designer cults with their own language, codes and lifestyles. …Computer-generated info-domains are the next frontiers.”[22] In 2011, Columbia Law Professor Timothy Wu remarked that machines now mediate so much of our lives that we must create new understandings of “cyborg law, that is to say the law of augmented humans.” Wu elaborated:

[I]n all these science fiction stories, there’s always this thing that bolts into somebody’s head or you become half robot or you have a really strong arm that can throw boulders or something. But what is the difference between that and having a phone with you—sorry, a computer with you—all the time that is tracking where you are, which you’re using for storing all of your personal information, your memories, your friends, your communications, that knows where you are and does all kinds of powerful things and speaks different languages? I mean, with our phones we are actually technologically enhanced creatures, and those technological enhancements, which we have basically attached to our bodies, also make us vulnerable to more government supervision, privacy invasions, and so on…. What we’re confused about is that this cyborg thing, you know, the part of us that’s not human, nonorganic, has no rights. But we as humans have rights, but the divide is becoming very small. I mean, it’s on your body at all times.[23]

Here is where the story gets really interesting. Computer-mediated social and work interaction has become the new norm in our coronavirus age of quarantines, face masks, and “physical distancing.” The new ritual of the “fake commute” has been coined to address the physical and mental health stresses of individuals whose work and lifestyle routines have been upended by COVID-19.[24] We all rely on linked digital technologies of one sort or another, from electronic mail, texting, GPS, and online shopping to Web-based “chat-rooms,” Zoom and Skype and FaceTime or other video conferencing platforms, online classes, online reading clubs, and an extraordinary range of audio and visual entertainment. And the latest findings in neuroscience show that continual computer use is literally re-wiring our brains. Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (2010), has stated that screen time is not by any measure equivalent to learning time:

The Internet is an interruption system. It seizes our attention only to scramble it. There’s the problem of hypertext and the many different kinds of media coming at us simultaneously. There’s also the fact that numerous studies—including one that tracked eye movement, one that surveyed people, and even one that examined the habits displayed by users of two academic databases—show that we start to read faster and less thoroughly as soon as we go online. Plus, the Internet has a hundred ways of distracting us from our onscreen reading.[25]

In this year of digital and remote learning, millions of young schoolchildren (including my own son and daughter) are getting only limited (sometimes only one or two) days of formal school a week, with the rest of their educations outsourced to Zoom video calls and/or learning “apps” like Seesaw and other online providers. During the most restrictive periods, primary and secondary schools have been shuttered and replaced with 100% online learning schedules; some schools have even supplied kindergarteners with iPad digital tablets. The halls of higher education also echo from empty classrooms, traditional face-to-face learning replaced by video calls, video lectures, and online blackboards. At all levels, Zoom teaching is a temporarily useful but qualitatively less satisfactory substitute for personal instruction, as many students, parents, teachers, and administrators acknowledge. Burnout from online meetings and online work coupled with protracted physical isolation from other human beings is a real and burdensome phenomenon in schools and offices. “These days, when video chatting has to stand in for a whole social life’s worth of in-person contact, it feels like a massive downgrade,” wrote Christina Cauterucci. “Every Zoom call brings a painful reminder of what quarantined life is missing.”[26] However, as coronavirus cases surge and physical distancing orders persist in order to stem new infections, K-12 school boards have had to cut costs and retool; many institutions of higher learning have had to refund room and board fees to students and cover additional costs associated with transitioning to remote learning.

In a recent Pew national survey, 68% of adults said that an online course did not measure up to an in-person course; and among college graduates, online classes were simply not as popular as in-person courses. About 75% of respondents with bachelor’s degrees or higher said online classes did not provide “an equal educational value.”[27] Respondents included, naturally, recently-graduated seniors who had just completed their college careers with a remote final semester capped off by a “virtual graduation” in 2020.

In the coronavirus age, teachers and staff have been or are being fired and furloughed at an alarming rate following the financial meltdown of many colleges and universities in America and the world. Educators are right to be more than a little concerned about the problem of moral hazard here—to lay off faculty and staff is to eviscerate the substance of education, at least as the better angels of our nature envisioned it.[28] Like Davide D’Urbino, a chemistry teacher at Clover Hill High School in Chesterfield County, Virginia, educators nationwide have had to scramble to meet unprecedented pedagogical challenges. “The expectation was that you could teach new stuff [online], but then you have to go back in class and reteach it,” D’Urbino said.”[29] D’Urbino’s frustrations are echoed by students at over sixty colleges and universities who are demanding tuition refunds, given the perceived decline in the quality of their education.[30]

The online world is rich and vast, full of information and potential remote contacts that span the globe, all available at the touch of a fingertip. Smartphones, tablets and laptops eat with us and sleep with us and can also deprive us of sleep. Such powerful tools offer many potential rewards and conveniences. But as Nicholas Carr cogently wrote in The Shallows, along with the indubitable benefits of digi-tech come certain costs to our integrity as human beings:

Our willingness, even eagerness, to enter into what [Norman] Doidge calls ‘a single, larger system’ with our data-processing devices is an outgrowth not only of the characteristics of the digital computer as an informational medium but of the characteristics of our socially adapted brains. While this cybernetic blurring of mind and machine may allow us to carry out certain cognitive tasks far more efficiently…as the many studies of hypertext and multimedia show, our ability to learn can be severely compromised when our brains become overloaded with diverse stimuli online. More information can mean less knowledge.”[31]

Worse yet than more information generating less knowledge, it could mean less understanding. These observations are important for the cyberpunk age, especially in 2020—the “Year of the Coronavirus.” Nicholas Carr is not against information technology, but rather the uncritical creeping substitution of digital information for real, self-generated, critical knowledge in the brain. Carr is neither a knee-jerk alarmist nor an anti-technological Luddite, and neither am I. Remote learning is a valuable tool, and the potential practical benefits of technology-assisted learning, especially in this dangerous coronavirus age, are evident. My argument in studying Bruce Lee, cyberpunk, and the deleterious effects of coronavirus is that we must be cognizant of the weighty and often fateful physical and moral choices we must make. Let us examine what we stand to gain and what we are prepared to lose in our new “brave new world.”

Information is all about us, and there can be no doubt that the ease with which we access it facilitates our research. But the manner in which it is filtered by search engines and cyber tools conditions our very thought processes and senses of priority. Nicholas Carr cites James Evans, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, who compiled a gigantic database of 34 million scholarly articles published from 1945 to 2005. Evans analyzed academic citations to study whether patterns of citation and research have changed as journals shifted from print to online formats. What he discovered was that “as more journals moved online, scholars actually cited fewer articles than they had before. And as old issues of printed journals were digitized and uploaded to the Web, scholars cited more recent articles with increasing frequency.” Moreover, “automated information-filtering tools, such as search engines, tend[ed] to serve as amplifiers of popularity, quickly establishing and then continually reinforcing a consensus about what information is important and what isn’t.”[32]

In other words, scholars (and others) can inadvertently shackle their own minds with cybernetic tools that they have neither created nor carefully scrutinized. As Bruce Lee said, articulating the problem ahead of his time, “When the mind is tethered to a center, naturally it is not free; it can move only within the limits of that center.”[33] Like it or not, we in the industrialized and networked world are living a cyberpunk reality, connected to digital devices that have become a part of us. In June 2014, in Riley v. California, U.S. Supreme Court justices unanimously stated that police officers may not, without a warrant, search the data on a cell phone seized during an arrest. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts declared that “modern cell phones . . . are now such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that the proverbial visitor from Mars might conclude they were an important feature of human anatomy.”[34]

Cutting-edge discoveries in biological and neurological science are illuminating the plasticity of our brains—how our brains and neural pathways and synapses change through experience, and particularly through repeated activity. The human brain is “very plastic,” said neuroscientist James Olds, for “The brain has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly, altering the way it functions.”[35] The scientific literature is far too vast to cite in full, but for a representative sample of essential books, I would suggest Eric Kandel’s In Search of Memory (2006); Norman Doidge’s The Brain that Changes Itself (2007); James Flynn’s What is Intelligence? (2007); and Torkel Klingberg’s The Overflowing Brain (2008).[36] These works show how one’s neurological pathways are being biologically, cybernetically and unconsciously rerouted by Internet use, necessitating no desire or conscious intention to manipulate one’s own mind or brain. Repeated physical motion and repeated clicking and reading and scanning create deeper brain manipulations than a layperson might suppose—and our cyber brains are changing much faster than what cyberpunks would call the “meat” brains of the human past. As neurobiologist Michael Merzenich put it in 2005, “Contemporary humans can experience “millions of ‘practice’ events . . . that the average human a thousand years ago had absolutely no exposure to.” Our brains,” he argued, “are massively remodeled by this exposure.”[37]

Technology mediates our social relationships and our identities, at the same time constituting an inescapable form of self-augmentation. This has been especially true during the coronavirus pandemic, which has forced so many people to work remotely. We are now reluctant cyberpunks, whose worlds are kingdoms of the screen. We lecture remotely to students who would rather see us in person but must make do with their own little windows on smartphones and computing devices; and as with education and business, sociality has also gone remote. “The Cyberpunk view of the world,” as Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows noted, “is also one which recognizes the shrinking of public space and the increasing privatization of many aspects of social life. Close face-to-face social relationships, save those with kin and significant others within highly bounded locales, are becoming increasingly difficult to form.”[38]

At the very least, we must beware of the ease with which digital convenience bleeds into a collective obviation of human contact and accountability. With so much of modern life tied to the global data “cloud,” scarcely any transaction can be wholly private, and data is collected from individuals without their knowledge or consent, using much the same data-analytics technology for advertising as for surveillance. Anna Wiener writes of the hubris of the cloud-addicted tech industry, “The idea of the cloud, its implied transparency and ephemerality, concealed the physical reality: the cloud was just a network of hardware, storing data indefinitely.” To what end? “Growth at any cost. Scale above all. Disrupt, then dominate. At the end of the idea: A world improved by companies improved by data. A world of actionable metrics, in which developers would never stop optimizing and users would never stop looking at their screens. A world freed of decision-making, the unnecessary friction of human behavior, where everything…could be optimized, prioritized, monetized, and controlled.”[39]

Cyberpunk is about the control, command, and confining of information by institutions of all sorts. In “We’re on the Brink of Cyberpunk,” Kelsey D. Atherton declared:

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps through the world, it collides with governments in the West that have spent decades deliberately shedding power, capability, and responsibility, reducing themselves to little more than vestigial organs that coordinate public-private partnerships of civic responsibility. This hollowing of the state began in earnest in the 1980s, and the science fiction of that time—the earliest texts of Cyberpunk—imagines what happens when that process is complete. Cyberpunk is a genre of vast corporate power and acute personal deprivation.”[40]

Cyberpunk, formerly just a science-fictional concept, is taking the ivory tower by storm and is in danger of vitiating its moral compass of academic responsibility. As Atherton notes, the pandemic did not cause, but rather exposed, the historical results of an increasing lack of accountability of corporate powers and states to consumers and constituents. What it has also done, as I will argue, is reveal ominous excesses of the information economy: entire economies of xenophobia and misinformation.

Chinaman in Cyberland

Perhaps the main difference is the fact that Chinese hygiene is Yin (softness), while Western is Yang (positiveness). We can compare the Western mind with an oak tree that stands firm and rigid against the strong wind. When the wind becomes stronger, the oak tree cracks. The Chinese mind, on the other hand, is like the bamboo that bends with the strong wind.

— Bruce Lee[41]

Let us now return to Bruce Lee for clarification of these points. Bruce Lee was a martial artist, thinker, and educator who had an eclectic hand in every branch of learning, and who fought against the overt as well as the incipient racism of his time. Lee abhorred nativism and exclusivity, for his stated purpose was the realization of human potential and the encouragement of its full expression in every individual.

The film Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993) is fictional and perhaps overly hagiographic, but in one telling scene, the open outlook of the protagonist is credibly portrayed. The elders of Chinatown say to Bruce that he cannot teach Chinese martial arts to the gwailo (literally, “foreign devils,” or Westerners); he counters that he will teach whoever wants to learn. A Chinese elder admonishes him, “One of the things we do not do is teach our secrets to whites, blacks. They are the enemy.”[42] To this, Bruce Lee responds, “They are not the enemy. They just don’t know us. We’ve been so closed for so long, they’ve never seen the real beauty of our culture—let’s show it to them.” The elders disagree and decide on a trial by combat.

This sets up the historical (and much-mythologized) Bruce Lee Chinatown duel with Wong Jack Man—“the most famous challenge match in kung fu history, retold and reinvented countless times in books, plays, and movies. …Wong Jack Man’s northern high-kicking style versus Bruce Lee’s southern fists of fury.”[43] According to credible accounts (Wong Jack Man’s supporters in Chinatown published a slew of disinformation claiming Lee’s defeat), the match ended ingloriously in about three minutes, with Wong running away and Bruce Lee raining down punches on his head, yelling, “Admit you lost! Say it! Admit you lost!”[44] Lee went on to teach his craft to anyone who was willing to learn; but this fight “was the turning point that led him to abandon his traditional style of kung fu.” The duel had disgusted Lee with its Chinatown-centered intolerance and had left him winded from the three-minute flurry. From then on, Lee would devote himself to painstaking physical conditioning and the creation of a new way of martial arts, one that emphasized the adaptability of the individual, which was far more important than any “style.”[45]

In Bruce Lee’s opinion, human beings could not advance in any form of martial arts by endlessly repeating set forms in karate, judo, traditional kung fu, or any other “national” style. He consciously and scientifically researched the useful techniques from many martial arts traditions and applied them to what he called Jeet Kune Do 截拳道 (“Way of the Intercepting Fist”): a transnational non-“style” par excellence. It was a philosophy and a fighting approach that was dead-set against fixed, mechanical, prejudicial knowledge. Bruce Lee explained:

So no matter what propaganda has been spread throughout the centuries, a classical style comes about as a result of a human being. … The founder might be exposed to a partial truth, but as time goes by this partial truth becomes a sect, a law, or—worse still—a prejudicial faith. … So what might have started off as some sort of personal fluidity on the part of its founder is now solidified knowledge, preserved and packaged for many younger generations as well as worldwide mass distribution, as well as mass indoctrination. …By the way, plastic plants might look pretty—that is, if you like dead things.[46]

Bruce Lee was an advocate for genuine teaching—substance, not form; punches and kicks, not words or fancy movements; and free action, not “routine efficiency.” He stated to Pierre Berton in 1971:

To me, ultimately, martial art means honestly expressing yourself, . . . [which] is very difficult to do. I mean, it is easy for me to put on a show and be cocky…or I can make all kinds of phony things, you see what I mean? And be blinded by it. Or I can show you some really fancy movement. But to express oneself honestly—not lying to oneself…that, my friend is very hard to do.”[47]

Bruce Lee fervently believed that real, hard, physical combat was the best teacher––a martial arts philosophy that was well-suited to the tumultuous times in which he lived. Recall that the 1960s and 1970s was a period when the fight for civil rights was engulfing America.

That battle is ever present in the age of the coronavirus, at a time when racism directed against people of color, immigrants, Asian-Americans, and Asians in general is on the rise in the Western world.[48] In 2020, U.S. anti-immigration policies and travel restrictions (not all of them related to the coronavirus) posed a serious threat to America’s diversity and competitive edge in research and innovation. International student visas were categorically denied to applicants from Middle Eastern, Asian, and African countries, a restriction that “reinforces the notion that the US is hostile to foreigners and that international students would be better off pursuing opportunities in the United Kingdom, Canada, or even China.”[49] But without international students, American universities will lose millions of dollars in revenue, the American economy will lose billions, and “the United States will be deprived of the significant contributions that foreign students make in many fields.” In the words of Charles Dunst, “[President] Trump is so blinded by xenophobia that he cannot see the benefits international students offer. Instead, his ‘America First’ administration at best considers them leeches on the American system, and, at worst, deems them nefarious spies to be kept out of fortress America.”[50]

But the racist rhetoric directed against China for allegedly “causing” and carrying the coronavirus in 2020 was not just a call to “Go Back to China”; it was an invitation from large numbers of people to repeat America’s unjust past and its past mistakes. The “Chinese virus” mantra and the cyber-directed attacks against Chinese-owned communications platforms like WeChat and TikTok—even the forced closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston (“a microcosm, we believe, of a broader network of [cyber-spying] individuals in more than 25 cities,” according to a US Justice Department official[51])—were racially-tainted provocations spurred by the American fear of a rising China and the terror of “Chinese spies” among us.

In the first months of 2020, as the United States began to feel the effects of the coronavirus, across the Pacific, Chinese netizens expressed concern that American media outlets were filled with speculation, information, and especially misinformation about China. They rightly identified this as cyber “China bashing.” Especially egregious were the claims that Chinese people in America were spies.[52] This called to mind not only the Cold War with the Soviet Union, but also the fresh memory of Wen Ho Lee, a Chinese-American scientist who was jailed in solitary confinement without bail for 278 days until September 13, 2000 for “mishandling” documents. As historian Erika Lee observed, “Chinese Americans have found that their loyalty to the United States has been questioned. They have been treated as dangerous foreigners rather than full-fledged U.S. citizens. This has happened in countless everyday interactions, as well as in high-profile investigations, acts of violence, and discriminatory racial profiling by government agencies.”[53] The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated a problem faced by Chinese Americans, who now found themselves blamed for spreading disease in America.

For example, on 2 March 2020, Fox News carried the following exchange:

JESSE WATTERS: I ask the Chinese for a formal apology. This coronavirus originated in China, and I have not heard one word from the Chinese, a simple ‘I'm sorry’ would do. So [I’m] demanding a formal apology from the Chinese people.

DANA PERINO: What if the outbreak had started here?

WATTERS: It didn’t start here, Dana, and I’ll tell you why it started in China. ‘Cause they have these markets where they’re eating raw bats and snakes…They are very hungry people. The Chinese Communist government cannot feed the people. And they are desperate, this food is uncooked, it is unsafe. And that is why scientists believe that’s where it originated from.

Video of this dialogue (Figure 2, pictured above) almost immediately went viral on China’s social media. Chinese netizens were highly attuned to American invective, and they reacted with fury on Internet domains (despite their own criticisms of the Chinese government for its handling of the coronavirus and its suppression of free speech).[54]

But the insults kept rolling in: on February 3, the Wall Street Journal published an editorial on China’s handling of the coronavirus with the offensive title, “China is the Real Sick Man of Asia.”[55] The sobriquet “Sick Man of Asia” (Dongya bingfu) is, of course, a derogatory coinage from the turn of the 20th century used to denigrate China’s perceived weakness in the face of Western and Japanese imperialism. In Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury, he showed up in a Karate dojo carrying a framed Japanese sign inscribed with the words “東亞病夫” (Sick Man of Asia), which the Japanese had used to insult his Kung Fu academy. Lee proceeded to punch, kick, and smash in the faces of the entire Japanese martial arts student body before declaring that “We Chinese are not Sick Men!” and destroying the sign. (See Figure 3, below—be sure to turn on the video subtitles!) In the film, Bruce Lee compelled two arrogant Japanese karate students to chew up the paper sign, literally making them “eat their words.”[56] Shortly afterwards in the film, Lee also obliterated a racist signboard above the entrance to Shanghai Public Garden—one that read: “No Dogs and Chinese Allowed” (狗與華人不得入內)—with a flying jump-kick.

If Bruce Lee were still alive in the time of coronavirus, his probable response would be to force Jesse Watters to “eat his words,” figuratively rather than literally. In his short life, Lee created a new image of a Chinese-American man, one who redefined Chinese masculinity even as he also redefined American-ness. Film critic Davis Miller, who stepped into a theater in 1973 to see Enter the Dragon,[57] wrote that “My hands shook…Bruce Lee launched into the first real kick I had ever seen. My jaw fell open like the business end of a refuse lorry. This man could fly. …Bruce Lee was unlike anyone I (or any of us) had seen.” Paul Bowman writes, “all of these accounts [from moviegoers encountering Lee] describe this same moment: once, I was one way; then I saw Bruce Lee, and that was the day everything changed.”[58]

Heady stuff. But in addition to revolutionizing martial arts in America (which he did by tearing down the ethnic and national hierarchies that separated them), Bruce Lee became a transnational sensation. In Bowman’s well-chosen words,

He became the first truly international film luminary (popular not only in the United States, Great Britain and Europe, but also in Asia, the Soviet Union, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent—in those pre-Spielberg days [when, it must be remembered] people in most nations were not particularly worshipful of the Hollywood hegemony)…. Lee has been credited with transforming intra- and inter-ethnic identification, cultural capital, and cultural fantasies in global popular culture, and in particular as having been central to revising the discursive constitutions and hierarchies of Eastern and Western models of masculinity.[59]

In short, Bruce Lee’s history and philosophy give every indication that today he would fight against the savage, spiteful, racist, and largely anonymous online portrayals of the Chinese and Asian peoples as spies and subversives in today’s world.

Lee would also combat the persistent stereotypes of Asian men as “Charlie Chans” or “Fu Manchus” and Asian women as “prostitutes” and “dragon ladies.” The prolific Chinese-American author Frank Chin has stated, “The most insidious part of the stereotype is… [that] when looking for masculine characteristics, you find none. … [In Western eyes, the Chinese] are waiters, laundrymen—okay, that’s old. And the new ones, you know, the good engineers, the nice doctors, all very nice, all very conservative…all passive. This makes them the ideal subject race, the ideal employees, the ideal servants.”[60]

Bruce Lee would most certainly have had an ally in Anna May Wong (1905-1961), the first Asian female movie star, who also chafed at the racist restrictions imposed on her as she acted in silent and sound film, stage, radio, and television. The period from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was a time when “Chinese” and “Asian” protagonists in Hollywood movies were played by white actors in yellowface. MGM Studios’ film “The Good Earth” [1937] provides an excellent example, featuring German-American actress Louise Rainer, who won the Best Actress Oscar award for playing the character of the demure Chinese wife O-Lan. It was also an era when songs like Bret Harte’s “Heathen Chinee” and “Chink Chink Chinaman” by Bert A. Williams and Alex Rogers were popular jingles.[61] In 1933, Anna May Wong told the L.A. Times: “I was so tired of the parts I had to play. Why is it that the screen Chinese is nearly always the villain of the piece, and so cruel a villain—murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass. We are not like that.” And Wong said, exasperated: “There seems little for me in Hollywood, because, rather than real Chinese, producers prefer Hungarians for Chinese roles…. Pathetic dying seemed to be the best thing I did.”[62]

Like Anna May Wong, Bruce Lee was unwilling to appear in anything that he felt demeaned his Chinese culture or his race. When Hollywood producer William Dozier called him in 1965, Bruce Lee was thrilled. As a veteran of twenty Hong Kong movies, Lee at first had not thought it viable to act in Hollywood, where there were so few roles for Asians. “If Bruce landed the part, he would achieve something historic. He would be the Jackie Robinson of Asian actors,” writes biographer Matthew Polly.[63] But Lee was offered only the role of Kato, the driver and sidekick of a white hero in The Green Hornet. “Lee reacted incredulously to being cast in a stereotypical role, recalling, ‘…I could immediately see the part—pigtails, chopsticks and ‘ah-so’s,’ shuffling obediently behind the master who has saved my life.’”[64] Daryl Joji Maeda, who calls Lee a “nomad of the Transpacific,” wrote that “Lee was uninterested in ‘typical houseboy stuff’ and told Dozier, ‘Look, if you [want to] sign me up with all that pigtail and hopping around jazz, forget it.’”[65] Lee ultimately took the limited role and made it his own, becoming, through his overwhelming kinetic energy, the undeclared star of the show.

Bruce Lee brought genuine martial arts to his role; his kung fu was real in a world of fakes. Stuntmen hated working with him, because “they were tired of getting hurt.” His movements were simply too fast. “Judo” Gene LeBell, a pro wrestler and judoka and the stunt coordinator on the set of The Green Hornet, said that “We did our best to slow Bruce Lee down because the Western way was the old John Wayne way where you reach from left field, tell a story, and then you hit the man. Bruce liked to throw thirty-seven kicks and twelve punches.”[66]

According to Matthew Polly, Bruce Lee insisted that his character of Kato was not a submissive manservant, but rather an equal with superior abilities: “They are making me the weapon. I’ll be doing all the fighting. …I’ll do all the chopping and kicking.” All this cost him dearly. “In nine years of marriage this nomadic family moved eleven times. Bruce may have felt rich, but he was actually getting screwed.… Despite being the second lead of the show, the Chinese guy was paid far less than the white actors.” Bruce Lee was the lowest-paid and hardest-working actor on the set of The Green Hornet. How much less for equal work? Bruce Lee (Kato): $400; Walter Brooke (District Attorney Scanlon): $750; Wende Wagner (Miss Case): $850; Lloyd Gough (Mike Axford): $1,000; Van Williams (Britt Reid/The Green Hornet): $2,000.[67]

Disappointed with his low pay and seriously worried about being able to provide for his family, Lee saw Hollywood’s racism against Asians, Native Americans, and African Americans as part of a systematic and closely interconnected denial of humanity. “I have to be a real human being,” he said, noting: “You never see a human-being Indian on television. … It’s about time we had an Oriental hero.”[68] Thus it was that Bruce Lee, trans-Pacific nomad, left Hollywood in 1970 to return to Hong Kong, sailing toward a transnational superstardom that he would not live to fully see. He would make his breakout films The Big Boss (1971) and Fists of Fury (1972) in Hong Kong for Chinese and Southeast Asian audiences, not the American audience that he had hoped to teach about martial arts.

In 2020, the idea of Asians as chopstick-holding, harmless hopping houseboys was replaced by notions of Asians as dangerous, bounding vectors of disease and economic destruction. The rampant misinformation about Asians as the “cause” and “super-spreaders” of Covid-19,[69] as well as the use of the offensive phrase “China Virus” in Europe and America, triggered a burst of outrage from mainland Chinese and the Chinese diaspora. The Chinese government demanded an apology for the editorial about “Sick Man of Asia,” and when the Wall Street Journal repeatedly refused to retract the term, China’s Foreign Ministry expelled three of the top U.S. journalists from the newspaper’s Beijing bureau on 18 February 2020.

The Year of the Coronavirus intensified political nativism in the United States, even seeming to normalize xenophobia in the context of fears around foreign diseases. For example, in a now-deleted Instagram post, U.C. Berkeley Health Services included on a list of “common reactions” to the coronavirus outbreak “anger” and “xenophobia” (the latter defined as “fears about interacting with those who might be from Asia and guilt about those feelings”). The post then cautioned students to “please recognize that experiencing any of these can be normal reactions,” for which the university later apologized after online criticism.[70] “There is heightened public panic when diseases are associated with the ‘Racial other,’” sociologist Charles Adeyanju wrote in February 2020. “The Chinese have become North America’s ‘model immigrants’ due to their economic success…. However, their ‘rising’ has constituted a psychological and economic threat to the populations that once derided them as less than human.”[71] To understand how such “public panic” can operate, let us view contemporary events in historical perspective, examining times when the Chinese were far from “model immigrants” in the eyes of most Americans.

The “Diseased” Chinese on the Shores of America

No matter what the reason is, followers are being enclosed and controlled within a style’s limitation, which is certainly less than their own human potential. Like anything else, prolonged imitative drilling will certainly promote mechanical precision and habitual routine security. … Thus any special technique, however cleverly designed, is actually a disease, should one become obsessed with it. … [Students of martial arts] are constantly on the search for that teacher who “satisfies” their particular diseases.

— Bruce Lee[72]

A knife-wielding white woman spewing racial abuse attacked Vietnamese-Australian sisters Rosa and Sophie Do in their hometown of New South Wales. Rosa and Sophie were called “Asian whores,” “Asian dogs,” and “Asian sluts,” and they were blamed for a terrible disease.[73] Sadly, this is not some hoary old racist propaganda from well over a century ago; the event occurred in March 2020, and the disease was the coronavirus. Such wild imaginings seem to keep popping up when it comes to the Chinese and disease, especially in the English-speaking world. This has been true for decades; the Chinese have long been named as the cause of the flu. A letter to Time magazine on 14 February 1969 complained that the term “Hong Kong Flu” was inaccurate, and that, because the influenza virus “was probably manufactured in secret laboratories on mainland China—it should be called Flu Manchu,”[74] the same term that would be revived in 2020. The multiple ideas––that the Chinese are: 1) less than human; 2) deliberately exporting disease to America and Europe; and 3) such machine-like non-humans that they can resist the same disease that they are exporting so virulently—were patently false back in 1969, but they have been once again trotted out in 2020 as “evidence” of a Chinese plot against America that bears a resemblance to that of the vile Dr. Fu Manchu, who once planned to take over the world from his secret lab. I shall address this theme below.

American president Donald Trump stridently claimed that Covid-19, the coronavirus, originated as a bioweapon in a Chinese lab.[75] “We’re going to find out,” Trump said, “You’ll be learning [about this] in the not-too-distant future,” he maintained.[76] What we now know (thanks to Bob Woodward’s revealing new book, Rage[77]) is that as early as January 2020, long before the virus became a pandemic, Trump was called and fully informed about the threat of coronavirus by the Chinese government, but he deliberately chose to “play it down” and mislead the American public about its dangers, likening it to a mere case of the seasonal flu.[78]

White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany defended President Trump’s naming of the coronavirus as the “kung flu.” “The origin of the virus is China,” McEnany said in a press briefing, “It’s a fair thing to point out…. Well, President Trump is saying, ‘No, China, I will label this virus for its place of origin.’” Asked whether Trump regretted using the phrase “kung flu,” McEnany said that he did not. “The president never regrets putting the onus back on China,” she said, also saying, “The president does not believe it’s offensive.”[79]

Further fanning the flames, former Trump advisor Steven Bannon (an ardent critic of the Chinese government) funded and promoted a “scientific paper” allegedly authored by a respected Chinese virologist, Li-Meng Yan. The paper stated that the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 was likely engineered in a Chinese lab and intentionally released into the world.[80] Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University, harshly criticized the paper for its false and shoddy science, which she believes was “political propaganda” aimed at smearing China. “This paper is very deceptive to somebody without a scientific background, because it’s written in very technical language, using a lot of jargon that makes it sound as though it is a legitimate scientific paper,” Rasmussen wrote. “But anybody with an actual background in virology or molecular biology who reads this paper will realize that much of it is actually nonsense.”[81]

How has the political use of derogatory terms such as “kung flu” and “the Chinese virus” affected the transnational Asian diaspora? Former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang commented in April 2020 that he had gotten heartbreaking messages about Asian Americans “being spat on or attacked or assaulted around the country.” As the coronavirus spread across the U.S., Asians were not recognized as equal victims of the virus, but rather as its perpetrators. The “Chinese virus is definitely part of the lexicon at this point, and you know, I’ve heard of schoolchildren getting called the Chinese virus and being bullied mercilessly,” Yang said.[82]

As the coronavirus spread, there was a concomitant rise in anti-Asian hate speech and abuse in the English-speaking world, both in person and online. Links to a small sample of videos in the latter category are listed below:

In the United States of America:

Asians facing discrimination, violence amid coronavirus outbreak – ABC News (12 Mar. 2020)

Racism and xenophobia are on the rise as the coronavirus spreads – CNN (18 Feb. 2020)

In Australia:

Coronavirus: Anti-Chinese sentiment on the rise in Australia – News.com.au (30 Jan. 2020)

In the United Kingdom:

Coronavirus: Racism towards Chinese people in the UK on the rise – The Telegraph (12 Feb. 2020)

Coronavirus: Hate crimes against Chinese people in the UK on the rise – Sky News (5 May 2020)

On 17 September 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution condemning the rising tide of anti-Asian racism due to the spread of the coronavirus. House Resolution 908 was sponsored by Rep. Grace Meng (D-NY) and passed by a vote of 243 to 164, with 164 Republicans refusing to support a resolution condemning anti-Asian racism and discrimination. Meng stated: “Enough of the demeaning usages of ‘Chinese virus,’ ‘Wuhan virus,’ and ‘Kung-flu,’ especially from our nation’s leaders…enough of the scapegoating. Enough of using the Asian American community to stoke people’s fears about COVID-19.” For this, Rep. Grace Meng got hate speech voicemails from online racists.[83] “Hey, you look like a Chinese virus, you fat slob. Or maybe ‘Kung Flu,’ you fat slob,” one caller said. Another opened with, “I’m calling about the ‘Karate Kid’ virus or the ‘Kung Flu’ virus.” Another: “I’ll call the FBI and put you in jail, you dumb*** motherf***er….F*** you….” Meanwhile, another claimed, “It’s not racist, it’s the truth. Filthy people.”[84]

The notion of the Chinese and Asian people as “filthy” carriers of disease has a lengthy, ignominious pedigree in America. Anti-Chinese sentiment, whipped up by the likes of Denis Kearney and the “California Workingman’s Party,” found expression in legal rulings that deemed the Chinese “inferior and incapable of progress” (1854: The People vs. Hall) and in periodic outbursts of deadly violence: The Chinese Massacre in Los Angeles in 1871; the Rock Springs Massacre in Wyoming in 1885; Anti-Chinese riots in California, Oregon, Nevada, Alaska, Colorado, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Washington in 1885–1886, including the Seattle Riot, in which almost every Chinese resident was evicted from the city. In 1887, white robbers murdered and mutilated the corpses of 34 Chinese gold miners, tossing them into the Snake River, where their mangled bodies showed up 65 miles downstream in Lewiston, Idaho. As a result, Hells Canyon, Oregon, where the atrocities occurred, was renamed “Chinese Massacre Cove.” No one was held accountable, although, in the words of Judge Joseph K. Vincent of Idaho, “it was the most cold-blooded, cowardly treachery I have ever heard tell of on this coast…every one was shot and cut up and stripped and thrown in the river.”[85] After the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, thousands of “white looters had a field day” pillaging the charred remains of Chinatown, and afterwards those same white men howled in protest that the Chinese refugees might settle in their neighborhoods.[86]

Most vital from the standpoint of our cultural history, Chinese immigrants have been identified not only as bearers of filth and disease, but also as subhuman animals or inhuman machines. In the words of Senator A. Sargent, “Should we be a mere slop-pail into which all the dregs of humanity should be poured? … The Chinaman can live on a dead rat and a few handfuls of rice…work for ten cents a day….”; to which California Senator John Miller echoed: “The Chinese are machine-like… they are automatic engines of flesh and blood; they herd together like beasts. …. We ask you to secure the American Anglo Saxon civilization without contamination or adulteration….”[87] Contamination and adulteration: such words carried the whole narrative of Chinese inferiority. It is a shameful fact that the 1875 Page Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 were the first and only American immigration laws ever to ban entry to one group of people based on race or nationality. In 1881, no less than eleven different bills were submitted calling for Chinese exclusion.

The American popular press reinforced negative attitudes toward the Chinese with demeaning images. Let us take a moment to examine two such images. Although the San Francisco Call’s newssheet (Figure 4 below) was printed in 1901, it employs the same hateful rhetoric of the 1870s and 80s, accusing the Chinese of sinisterly coming across the Pacific to steal American jobs and pollute the country’s integrity. The upper-left-hand box quotes Mayor James D. Phelan’s address at the Chinese Exclusion Convention: “We are the warders of the Golden Gate…and if there is any danger or trial it is for us to sound the alarm. I regard the Chinese question as a race question. I regard it as an international question; and above and over all, a question involving the preservation of our civilization.”

This rhetoric echoes earlier sentiment from the 19th century, which claimed that the Chinese were dirty and diseased by nature. See the image of an advertisement for the “Magic Washer” from 1886 (Figure 5 below)—this product apparently serving much the same function that hand sanitizer does today in the coronavirus pandemic: to ward off “Chinese” germs.

“The Chinese Must Go,” the advertisement proudly declares, and we must all use Magic Washer in order to avoid being “dirty.” No family should go without it (except, of course, the Chinese. I would call your attention to the ominous slant-eyed face on the setting sun overlooking the Pacific Ocean). The images are clear: Asians bring defilement; Chinatowns, historically, were seen as dens of opium, prostitution, and sickness. “Why not discriminate?” asked California Senator John F. Miller. “America is a land resonant with the sweet voices of flaxen-haired children. We must preserve American Anglo-Saxon civilization without contamination or adulteration from the gangrene of Oriental civilization.”[88]

Not surprisingly, an outbreak of bubonic plague—the dreaded “Black Death”––at the turn of the century cemented the impressions of white Americans that the Chinese were filthy “rat-eaters” (just as Jesse Watters would publicly call the Chinese “bat-eaters” in 2020). The plague, which claimed an estimated six million victims in India from 1896 to 1906, found its way to Hawai’i in 1899, where “about 10,000 people—mainly Chinese and Japanese immigrants—were quarantined within the cordon or at the [containment] camps” and fumigated and disinfected with chemicals. On a Saturday morning, 20 Jan. 1900, the Honolulu fire department set fire to Chinatown, trying to burn the plague out. It did not work.[89]

On March 6, 1900, Chinese-American worker Wong Chut King (aka Chick Gin, Cheek Gun, and other variants) died of the bubonic plague in San Francisco’s Chinatown, his being the first plague case identified on mainland American soil. The bacteria was spread by fleas from infected rats, but it was blamed on the Chinese. In the face of this outbreak, Navy Surgeon General W.K. Van Reypen at first discounted the evidence, claiming: “It is a disease peculiar to the Orient and seldom, if ever, attacks Europeans…. There is absolutely no danger of the plague ever getting here.”[90]

Yet for the ten to fifteen thousand residents of San Francisco’s Chinatown, barbed wire and ropes were the new reality. “The police turned them back. Food deliveries were halted. Garbage collection stopped, leaving piles of rubbish on the street. Street cars were forbidden to pass through the area,” for Chinatown was condemned as diseased, its people deemed “an inferior race that had poor hygiene and, as a result, spread disease.”[91] Dr. Joseph Kinyoun, an idealistic and skilled bacteriologist of the Hygenic Laboratory (which later became the National Institutes of Health), tried mightily to stem the tide of anti-Asian racism in favor of a rational, scientific procedure to test for the plague bacteria, but he was mocked and derided by the San Francisco press, which reduced his laboratory experiments to a simple jingle that demeaned Asian-Americans as rat-eaters, with Kinyoun himself as their sponsor:

Health Board, Health Board,

Where are we at?

Guinea pig, guinea pig,

Rat, rat, rat![92]

Dr. Kinyoun, disgusted by the news coverage about the plague, stated flatly that “people here [are] absolutely in the dark as to [the] correct situation.”[93] In much the same way, in the 21st century, President Donald Trump publicly mocked Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading expert on infectious diseases, for warning Americans to wear masks and practice physical distancing to prevent coronavirus infection. “People are tired of hearing Fauci and all these idiots,” Trump said, declaring Dr. Fauci “a disaster.”[94] In 1900, when the bubonic plague hit San Francisco, California’s governor, Henry T. Gage, likewise stated that he would neither look at the evidence nor take action. Governor Gage was allied with business interests and knew a public health crisis would cost business. “Bubonic plague does not exist and has not existed within the State of California,” Gage claimed in a telegram to the U.S. Secretary of State.[95] Gage simply promoted hatred, sowed distrust, and wanted “Dr. Kinyoun’s head.” As Gail Jarrow explained: “The people of San Francisco didn’t care…they hated Joseph Kinyoun. There was no plague…. Kinyoun realized that he had become the scapegoat in the fight over plague’s existence in San Francisco. …His opponents criticized and blocked everything he did to control the threat of plague. He wrote his uncle, ‘I am at war with everybody out here.’”[96]

All evidence of the plague outbreak was squelched and denied by local businessmen, politicians, and the city’s big three newspapers—the Bulletin, the Call, and the Chronicle—which called the plague “fake.” This plague outbreak was invented, the papers claimed, simply to increase the health board’s funding. “The most dangerous plague which threatens San Francisco is not of the bubonic type,” wrote the Call, “It was the “plague of politics.” And white people took notice only because of the inconvenience; as the Chronicle complained, “The white employers of the Chinese awoke to find that there was nobody on hand to prepare breakfast.” Then, after noisily denying the plague’s existence for a year, Governor Gage addressed the California legislature with the outrageous accusation that Kinyoun was causing the plague outbreak by injecting imported plague samples into dead bodies to create positive tests![97]

California was torn apart by the plague over a century ago, even though the number of fatalities was relatively small.[98] In what the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has called “one of the most infamous chapters in U.S. public health history,” the events of the San Francisco plague took the low road of scapegoating and cast public health as a problem of race, not of science. If anyone was to blame, the American public felt, it was the Asiatic peoples, who had to be roped off behind barbed wire because they lived in overcrowded homes, had poor sanitation, foul drinking water, and bad nutrition, Asiatic qualities of life that allegedly acted as plague vectors, “the same way they spread cholera, typhus, and typhoid fever.”[99] Gage lost the California governorship to George Pardee in 1902, and only then did medical intervention finally stop the plague in 1904. “Apprehension that an epidemic might generate widespread furor and cause severe economic consequences encouraged the business interests to deny the truth,” wrote Philip Kalisch.[100] Fake news a century ago was still just that—fake news. And fake news sold back then, as it does now. Let us again view the present through the prism of the past.

The “Virus Lab” of Fu Manchu

During the current coronavirus crisis, the Trump White House took a page out of Henry Gage’s playbook from early 1900s California, demonizing Dr. Anthony Fauci,[101] in the same way that Gage once vilified and tried to discredit Dr. Joseph Kinyoun. And, like Navy Surgeon General Reypen, Governor Gage, and his business allies at the turn of the century, the U.S. government swung into denial once again, calling the coronavirus a “Fake News Media Conspiracy,” even as the number of infections and hospitalizations surged in the United States. “COVID, COVID, COVID,” President Trump tweeted: “We have made tremendous progress with the China Virus, but the Fake News refuses to talk about it this close to the Election.”[102] As Trump watched his poll ratings plummet in advance of the November 2020 presidential election, he vociferously blamed secret Chinese labs for manufacturing a bioweapon in a secret lab to doom the American way of life.[103] Meanwhile, some conspiracy-oriented writers have gone so far as to allege that the coronavirus was a preemptive strike and China’s equivalent to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, employing a string of fanciful racist names for the deadly virus, including “Chop Fluey,” “Lung Pow Sicken,” “the Communist Chinese Virus,” and, of course, “Kung Flu” and “Flu Manchu.”[104]

Such references to “Flu Manchu” naturally raise the specter of the fictional Fu Manchu, who planned to conquer and/or destroy the world from his secret lab. But why does Fu Manchu still prey upon our minds in 2020, when he was a creation of the 1910s and 1920s, a full century ago? Is the bad doctor not dead and desiccated? Contemporary politicians and popular writers have resurrected Fu Manchu as a bogeyman. As Shan Wu recently wrote, “the othering of Asians enjoys a long, dark history in American and Western culture. The concept of the ‘Yellow Peril’—hordes of Asians invading the West—surfaced in the 19th century, continuing into the 20th century with film characters like Fu Manchu and Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless.”[105] Fu Manchu was, quite simply, the quintessential Asian villain for all ages (and yes, he had a lab).

Scholar Crystal Anderson quoted Robert Lee’s description of Fu Manchu as “the archetype of the sado-masochistic Asian male character in American popular culture narratives of the twentieth century” and “the very definition of the alien, an agent of a distant threat who resides among us.[106] Edward Said, famous for his cogent critique of “Orientalism” (1978), once said that his most indelible visual images of China were those of “Chinamen,” those people whom he remembered having

their effect on me…[with] the Fu Manchu films and Charlie Chan.(...) We didn’t interact with Chinese people. So in a certain way these films also created divisions within the non-European world. But the most powerful thing about them was that they established the norm, which became unquestioning. And everything else was deviant, frightening and eccentric. They were and are very strong.[107]

British scholar Christopher Frayling wrote, “In America, the literary image of the Chinese as alien ‘other’—as sinister villain or dragon lady or comic laundryman or threatening heathen or broken blossom or doomed prostitute or member of a brutalized horde—grew out of Bret Harte, mining stories from gold-rush California, railroad and urban myths about bachelor societies, the Exclusion Act of 1882, and the anxieties the images embodied were mainly about immigration.”[108] What Frayling referred to are, in part, the apprehensions of the decline of the early-1900s British empire, on which the sun was finally setting. Frayling also pointed to the fact that scare-stories about the threatening transnational “Other” are actually twisted reflections of self-doubt. “The stories were about ‘us’—they were not really about China at all.”[109]

Why was China on the mind? Frayling recalled his own childhood experiences in early- to mid-1950s Britain, back when Bruce Lee was still just a troublesome boy picking fights in Hong Kong, just a boy trying to toughen up and be somebody.

We played a game called Chinese Chequers—with a Fu Manchu lookalike on the box, complete with long moustache and mandarin robe—and had Chinese conjuring sets, which were supplied with an ornate faux-ivory wand; we gave each other Chinese burns in the playground, bowled sneaky ‘Chinamen’ on the cricket field and joked in pidgin Chinese (‘Confucius, he say . . .’) …[during one river cruise up through London…] the amplified commentator pointed out that Limehouse was ‘the headquarters of Dr. Fu Manchu, where he planned to take over the world.’ All of this was, indeed, very difficult to remove from my head when I grew up. It stayed with me.”[110]

Such tropes as those described by Frayling, introduced by British popular culture to impressionable schoolchildren, disclosed the secret staying power of persistent anti-Chinese racial stereotypes. They claimed to be both scientific (labs, drugs, disease) and supernatural (mystical, disembodied).

“Doctor” Fu Manchu was a yellow, undead vampire-like creature; he was also a wicked genius. More importantly, Fu Manchu was a person who could be fought and defeated, unlike the plague, which was, in the words of Gail Jarrow, “like a phantom haunting the land, the killer [that] took the lives of the lowliest beasts to the greatest human leaders. …The wisest physicians were no match. Potions and remedies failed to cure.”[111] Prior to British author Sax Rohmer’s creation of Dr. Fu Manchu, the Yellow Peril was diffuse and elusive, embodied in opium dens and fanatic “Boxer” mobs more than in any single person. The evil doctor’s wiliest opponent was Scotland Yard detective Nayland Smith, a character who “corresponds to the culmination of the collective desire of the imperialist bloc for a representative figure (‘the man who fought on behalf of the white race’) in opposition to the diabolic Fu Manchu (‘the head of the great Yellow Movement’).”[112] Hollywood Orientalism, drawing from British inspirations, was thus responding to popular demand and “firmly embedded in the logic of late capitalism.”[113] Evil had to have a face and a body.

The bodies of Asians were encountered by British and American interlocutors in the early 20th century with “(1) an almost superstitious dread of Orientals and a tendency to portray them as animals and/or vampire-like living dead parasites and (2) a preoccupation with the role of English women in the opium den accompanied by the suggestion that they are being Orientalized and assimilated.”[114] Thus, Fu Manchu had a secret headquarters in which he conducted lascivious experiments in drugs and diseases and moral corruption, and he tried to poison the Anglo-Saxon world from his lab. In The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), the film plot involved the kidnapping of scientist Prof. Muller, who had discovered how to distill poison from the Tibetan black hill poppy. Fu Manchu wanted to use the poison to infect the world, but in the end, Nayland Smith of Scotland Yard appeared to have blown Fu Manchu and his poisoned poppy seeds to smithereens. Yet Fu’s face, superimposed on the wall of his burning laboratory, sent the following message: “The world shall hear from me again!”[115] Across a baker’s dozen of original Sax Rohmer novels and a slew of spin-off stories, movies, radio and comic-book dramas, Fu Manchu was virtually unkillable. Fu Manchu was “‘the Yellow Peril incarnate in one man’: a man of mysterious malignance, possessed by an unexplained hatred of Caucasians and a desire for global domination.”[116]