Abstract

This paper discusses Xu Nianci’s strategies for promoting his political and feminist ideas in the feminist utopian novel Qingtian zhaiand contextualizes these discussions in late Qing progressive intellectuals’ efforts for national salvation. In the novel, Xu imagines a utopian future for China and depicts highly metaphorical dreams about sleeping Chinese, dark prisons, and bloody massacres. These are his strategies to criticize China’s backwardness, social injustices and people’s numbness toward and desire for escapism from national crises. He also uses them to appeal to the public for deeper patriotic commitment. As a supporter of women’s rights, he fakes female authorship for Qingtian zhaito encourage women to become writers. In the story, he portrays major female characters as female heroines and constructs a women’s sphere bonded by a sisterhood based on a shared political goal. This paper also argues that Xu’s political and feminist agendas are radical but peaceful. He advocates revolution as a necessary solution but focuses more on peaceful reforms in political organizations, education, and publishing as support systems for revolution. He makes radical arguments for women’s rights but as a male author, his attention to women’s interests per se is not enough. He subordinates women’s issues to a nationalist agenda and proposes peaceful solutions to women’s problems such as marriage. He suggests collaboration as a solution by characterizing most male characters as supporters of women.

Keywords

Utopia, Feminism, Political Novel, Xu Nianci, Qingtian zhai

Introduction

Qingtian zhai 情天債 (Debts in the Realm of Love) (1904) with its horn-title “nüzi aiguo xiaoshuo 女子愛國小說 (a novel of women’s patriotism),” is a feminist utopian novel written by Xu Nianci 徐念慈 (1875-1908) under the pen name “Donghai juewo 東海覺我 (One awakened by the East China Sea).” Xu was a progressive writer, translator, publisher, and Female Subjectivity and the Transnational Imagination in the Essays of Chen Xuezhao, Lu Yin, and Okamoto Kanokoeducator active in the late Qing reform era (1895-1912). [1] He only completed a wedge and the first four chapters of the novel. They were serialized in the first four issues of an important modern Chinese feminist journal, Nüzi shijie 女子世界 (Women’s World), to which Xu was one of the major contributors. The finished part of the novel mainly narrates a meeting held in 1904 by the revolutionary organization “Zili hui自立會 (Independence Society)” to deal with a potential unequal treaty signed between the Qing government and an alliance of six countries: the UK, the US, France, Germany, Japan, and Russia. At the meeting, the female revolutionary Su Huameng 苏華夢 proposes to lead an investigation team to collect intelligence in Japan and Russia before creating a plan for a solution, and the proposal is widely accepted. To the main story, Xu adds the opening of a utopian future, depictions of metaphorical dreams, and extensive introductions to the main characters and institutions involved in the story, making the novel both profound and politically instructive.

This study discusses these figurative devices, Xu’s techniques of characterization, and his faking of the female authorship of Qingtian zhai as strategies for promoting his ideas of revolution, patriotism, and feminism. It contextualizes these discussions in late Qing progressive intellectuals’ incessant efforts toward national salvation and argues that in Qingtian zhai, the political and feminist agendas Xu proposes are radical but peaceful ones. China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) led to the Hundred Days Reform (1898) and comprehensive cultural and social reforms in areas such as education, publication, and women’s rights. When the Hundred Days Reform failed, some intellectuals turned to radical revolution. The promotion of revolutionary ideas culminated and was also thwarted by the Qing government in the “Subao an 蘇報案 (Subao case)” (1903), while social reforms continued. It is in this context that in the story of Qingtian zhai, Xu proposes a “radical but peaceful” political agenda that uses social reforms as the support system for revolution. As a male author, he offers a feminist agenda that has the same features. While making radical calls for women’s rights, he subordinates his feminist calls to a nationalist agenda, providing peaceful answers to women’s problems. He implicitly suggests collaboration between men and women as a solution by characterizing most of the male characters in the novel as supporters of women.

Figure 1. A portrait of Xu Nianci. Source: https://www.laoziliao.net/cnmr/info/5827-XU_NIANCI

Utopian Future and Dreamscape: Strategies for Political Criticism and Appeal

In “Preface on the Translation and Publication of Political Novels,” Liang Qichao proposes to learn from the West and Japan, using the political novel as a tool for educating the Chinese people and promoting political reform:

What cannot be taught with the six classics, should be taught with the novel; what cannot be instilled through the standard history, should be instilled through the novel; what cannot be inculcated by the Analects , should be inculcated by the novel; what cannot be governed by the law, should be governed by the novel…For countries including America, England, Germany, France, Austria, Italy, and Japan, their daily political progress should be mostly attributed to the political novel. As a British gentleman said, the novel is the soul of all the citizens. [2]

Liang’s promotion of the political novel triggered a short-lived “political novel fever” among Chinese progressive intellectuals during the 1900s and 1910s. [3] Many writers at the time followed Liang’s lead and wrote political novels. As one of them, Xu Nianci published the utopian novel Qingtian zhaiin 1904. Like Liang Qichao, he also emphasizes the positive impact novels can have on Chinese society and people. In “My Views of the Novel,” he argues that “the novel among all the literary genres is the catalyst for promoting social development and it cultivates people’s dispositions in an entertaining form.” [4] Furthermore, among different fictional genres, he shows his preference for novels concerning “shehui taidu 社會態度 (social affairs and public opinion),” military novels, adventure novels, science fiction novels, and novels involving “lizhi 立志 (aspirations)” because they can teach readers to “take their responsibilities as national citizens, explore all the dangerous waters and lands, elucidate the essence of learning, establish themselves and deal with the world.” [5] He also expresses his concern about the fact that at the time these genres were much less popular among readers than certain entertaining fictional genres such as detective fiction and romance, according to a survey of sales figures. He does not directly mention “the political novel,” but Qingtian zhai can be categorized as either a novel concerning social affairs and public opinion or a novel involving aspirations according to his typology.

In this essay, I discuss Qingtian zhaias a political novel and, more specifically, a utopian novel. The utopian novel was a modern fictional genre imported from the West, and in early twentieth-century China, most utopian novels were political novels created with utopian imaginations. Utopian imaginations were not new to Chinese people at the time. Since ancient times, the ideal world has been depicted by philosophers and writers one generation after another, from the sage-king era in Confucius’s (551—479 BC) writings to the untouched village in Tao Yuanming’s 陶淵明 (ca. 365-427 AD) “Peach Blossom Spring.” However, as pointed out by Fokkema, “the nostalgia for a utopian past gives way to the idea of progress” [6] in modern times. The idea of progress that sets modern Chinese utopian works apart from previous writings is closely related to a linear time view in discourses of Western modernity. [7] This idea acted as an impetus propelling the modernization of Western countries before leading countries in the East Asian world, including Japan and China, to modernize their societies following the Western model. In the utopian imaginations of modern Chinese intellectuals such as Xu, the West serves as a model for China’s progress: nation-states with progressive political systems, strong economies, the most advanced technologies, a high standard of living, etc.

Based on the idea of progress, the future represents a higher level of socio-political development. In modern Chinese utopian novels such as Qingtian zhai , “future” as a literary trope functions as a powerful carrier of expectations, aspirations, dreams, and particularly, utopian imaginations. In 1902, Liang’s groundbreaking work Xin Zhongguo weilai ji 新中國未來記 (The Future of New China) pushed the weilai ji 未來記 (future record) subgenre onto the central stage of utopian writing. Following Liang’s successful practice, Chen Tianhua’s 陳天華 Shizi hou 獅子吼 (Lion’s Roar) (1905), Chun Fan’s春颿 Weilai shijie 未來世界 (The Future World) (1907), and Lu Shie’s陸士諤 Xin Zhongguo 新中國 (New China) (1910) all offered their respective versions of this utopia: a future China that was a powerful country. Liang’s novel starts with an account of a future Shanghai World Expo happening sixty years from the time point of the main story and uses this utopian narrative as the background. In Liang’s utopian imagination, China, sixty years into the future, becomes a modern country that is powerful politically, economically, militarily, and socially. From this vantage point, the main story looks backward to find out how China could make such achievements possible within sixty years. Qingtian zhai borrows this form of utopian writing, putting the utopian narrative into the background and focusing the main story on how to build a utopian future.

Figure 2. A drawing of an imagined future Chinese aircraft published in Dianshizhai huabao 點石齋畫報 (Stone-touching studio pictorial) (1884-1898).

Imagining China’s utopian future as a strategy

In Qingtian zhai,the story opens with a comprehensive utopian description of China in 1964, sixty years after the starting point of the main story of the heroine Su Huameng. The utopian narrative in the wedge is a strategy used to serve multiple purposes: to help with characterization, to criticize reality, and to make political appeals through an envisioning of the future of China.

In the narrative, the future China is depicted as being on an equal footing with other countries in the world and as a leader in Asia. It is a powerful and respectable country in every aspect: domestically, following the Constitution, local governments enjoy political autonomy and their governance is well-ordered; diplomatically, China maintains good relationships with other countries and they send dignified envoys to each other regularly; militarily, China has a large army and its citizens are all full of martial spirit; socially, China has achieved universal education and gained advanced scientific technologies. Immediately after these descriptions, the following sentences connect the utopian narrative with the main story: “Let’s think! How could China, which was an old and sick empire sixty years ago, suddenly change into what it is now? People all attribute it to the efforts of the first female revolutionary, the great heroine of our empire, Su Huameng.” [8] Therefore, Xu’s enthusiastic celebration of the future China helps to frame the protagonist Su Huameng as the heroine who made tremendous contributions toward turning China into a powerful country.

Since utopia is “where sociopolitical institutions, norms, and individual relationships are organized according to a more perfect principle than in the author’s community,” [9] utopian narratives always include explicit or implicit criticism of the current social realities. In the story, China sixty years ago is exactly the real world in which Xu lived. It is described as “an old and sick empire.” Its people are called “opium ghosts.” All the glories and achievements of the future China serve as a silent accusation of the weakness, backwardness, and inertia of China in the real world. In this sense, Xu’s utopian imagination about a new China shows his deep dissatisfaction with the real situation.

Structurally, the utopian future in the opening is used to elicit Xu’s proposals for saving China from its national crisis and building it up into a powerful country. Xu makes his proposals via the story of Su Huameng: the revolution that she leads and her efforts to achieve different forms of social reform. Right after the question, “How did the change happen?”, Su’s story begins. This question-answer format in the opening exemplifies the novel’s whole structure: The utopian future as happy ending is followed by Su’s story as the path that leads to that ending. In other words, the utopian narrative presents the outcome of Su’s revolution. Nevertheless, from the perspective of readers in 1904, the utopian narrative lists the goals of their contemporaneous revolutionaries like Su fighting for a bright future for China. By giving a detailed depiction of China’s progress in different aspects, Xu sets the agenda for the real-life revolutionaries of his time, pointing out that China is in urgent need of progress in its political governance, legal systems, international relations, military power, education, scientific technologies, and so on. In a word, Xu uses a utopian future to appeal to the public and mobilize people to fight for a new China. Setting goals through constructing a utopian world in the novel is one of his strategies to make political appeals.

Depicting metaphorical dreamscapes as a strategy

Another of Xu’s strategies is to use highly metaphorical depictions of dreamscapes to make harsh political criticism. Before discussing the dreams in the story, it is important to note that Su Huameng’s name puns on the notion of “awaking China from its dreams,” which is associated with the metaphor of a sleeping China. It implies that Su will be the heroine who makes China face up to its real situation and take action to solve its problems. This pun is also directly related to what happens in the first chapter of Qingtian zhai, which starts with a dream narrated in the first person by Su. Her dream has multiple scenes: the first scene features a group of people, some asleep, some just awakened by her, being brutally massacred; in the second scene, she is led out of a prison by two foreign soldiers; the third scene tells that on her way to a prosperous modern city, she is killed by a man accusing her of escaping from her responsibility to save China.

As mentioned above, the first scene presents a bloody massacre in which Su witnesses a group of people being ruthlessly killed in their sleep. She shouts in order to wake them up but most of them are reluctant to get up. Even those awakened by her remain unaware of the danger they are facing and end up being killed. In the end, Su trips over the body of a sleeper and passes out in a pool of blood. According to the dialogue between Su and her anonymous interlocutor in the third scene, the people who were killed in their sleep are the citizens of Huaxu guo[10]華胥國 (Huaxu country). They call themselves “hua ren華人 (Chinese people)” because they have forgotten the second character in their country’s name. Xu uses this sleep metaphor to criticize the Chinese people, who have no awareness of how grave the national crisis is and shirk their responsibilities to their nation. He warns that these numb and ignorant people who make no patriotic commitments will pay a heavy price.

The sleep metaphor has been widely used by modern Chinese writers to describe China’s inactivity while facing a grave national crisis. According to Rudolf G. Wagner, the earliest use of the sleep metaphor for China may be traced to an 1884 record of the Sino-French confrontation in Vietnam. [11] Later, the Chinese ambassador Zeng Jize曾紀澤 (1839–1890) used this metaphor in an influential English essay, “China: The Sleep and the Awakening” (1897). Liang Qichao coined the derivative metaphor “sleeping lion” for China in the essay “A Warning of Being Carved up Like a Melon” (1889). [12] Under their influences, the sleeping lion metaphor appeared in late Qing novels such as Shizi houandXin Zhongguo. The metaphor of sleeping Chinese people is also used by Xu Nianci more than once in his works. In his Xin faluo xiansheng tan 新法螺先生譚 (New tales of Mr. Braggadocio) (1905), acclaimed as the first complete work of modern Chinese science fiction, Mr. Braggadocio meets the ancestor of the Chinese people and finds out that the Chinese people are asleep and in urgent need of being awakened. The sleeping Chinese metaphor transforms into the “iron house” in Lu Xun’s 魯迅 (1881-1936) contemplations on how to save Chinese people, together with the element of imprisonment, another metaphor that is featured in the second scene of Su’s dream.

In this scene, the dark prison in which Su is locked is a metaphor for Chinese society that deprives people of their freedom and subjects them to unjust treatment through the use of coercive power. Su tries to find out why she is locked in the prison and why people are being killed but she concludes in her monologue: “There are no reasonable principles in this kind of world. Power is the only principle. If one day, I get some power, I must teach people in this world what the true principles are and see how they feel ashamed of themselves.” [13] “This kind of world” refers to a world full of chaos, injustices, coercion, and snobbishness. In such a world, there is no need to ask for reasons for her imprisonment and the previous massacre. In this monologue, Su also states her aspiration to educate the public, who, in her view, should be ashamed of their unawareness or tolerance of the lack of true principles in their world. In the end, Su is escorted out of the prison by two foreign soldiers, an event which is also highly metaphorical. The foreigners who have imprisoned Chinese people could also direct people like Su out. Such a metaphor can be associated with the “learning from the enemies (the West)” complex among late Qing reformists.

In the last scene, Su walks towards a modern coastal city, described as a “goldlike world”: commercially prosperous, with a convenient modern transportation system, including cars, railways, and seaports with different kinds of ships. On her way, she meets a person who does not allow her to continue her journey. He accuses her of pursuing personal interests in leaving for the new world while escaping her responsibility to save her nation and people from prison. His accusation is long and full of emotion, containing multiple strong statements such as “I am so vexed that I must kill each one of you who have forgotten who you are!” [14] In the end, he beheads her in great anger. This bloody final scene of “beheading escapists” expresses both Xu’s deep disappointment in those people who escape taking responsibility for their nation and his urgent appeal for people to take action.

As shown in Qingtian zhai, dreamscape depiction facilitates quick scene shifts and free expression of ideas or emotions in different narrative voices. Its flexibility enables the author to criticize reality by employing multiple devices. Metaphors that convey deep meanings such as the sleep metaphor or the dark prison can be turned into visible, tangible, and expressive scenes in dreams. Extreme emotions can be embodied in scenes of bloody massacres and killings. For example, in the last scene narrated in the first person by Su, fear and pain reach a crescendo when her head is chopped off. The dream makes what might be unreasonable in a realistic novel reasonable. It is through such dreamscape depictions that all of Xu’s harsh criticisms, sharp accusations, urgent appeals, and strong emotions can be set into full play.

All About Women: Strategies to Promote Women’s Rights

Xu Nianci was an active advocate for women’s rights. He made great contributions to the development of modern women’s education by building women’s schools and publishing women’s magazines. In September 1904, he worked with Ding Zuyin丁祖蔭 (1871-1930) to establish a women’s school called “Jinghua nüxuexiao” 竞化女學校 (Competition-Evolution Women’s School) in Changshu. In one of Xu’s biographies, written by Ding, Ding recalls that “he (Xu) said other than reforming women’s education, there will be no way to achieve universal education.” [15] In this school, Xu taught as a teacher and worked as the director for over two years. During roughly the same period, Xu also taught at another important modern women’s school, Aiguo nüxue 爱国女学 (Patriotic Women’s School), which was established by famous educators such as Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 (1868-1940). In January 1904, Ding started one of the most important women’s magazines in modern China, Nüzi shijie. Xu immediately became one of its main contributors, and Qingtian zhaiwas published in its first issue. In October 1904, Nüzi shijie started to be issued by the Xiaoshuolin she 小说林社 (Forest of Fiction Press), a publishing house newly established by Ding, Xu and Zeng Pu 曾樸 (1871-1935).

Qingtian zhai is a feminist political novel in which the promotion of women’s rights is a core part of the story. Xu also used particular strategies to make the story all about women and promote his feminist agenda.

Figure 3. Two cover pages of the magazine Nüzi shijie. Source:http://ccwm.china.com.cn/dc/2020-08/06/content_41247565.htm

From a woman: faking female authorship as a strategy

Xu in the voice of the narrator claims his wife’s authorship at the beginning of the work: “Thanks to my wife, who has been sharing all the pains and gains with me. She wrote a novel about some stories that took place decades ago. [16] Those stories can make people sing, make people dance, make people sad, make people cry. They are all told in detail in this novel named ‘Qingtian zhai’.” [17] No evidence exists to show that Xu’s wife was a writer capable of writing novels. It has been generally acknowledged that this authorship claim is fake, and Xu’s biographies and other historical records concerning Qingtian zhai would seem to support this assessment. Xu faked female authorship to show readers that women could also be talented writers and encourage more women to obtain an education and seek fulfillment for themselves outside the family. Under the guise of being a female author, Xu used the practice of writing Qingtian zhaito support the cultivation of female writers that he and his colleagues were promoting in the feminist journal Nüzi shijie.

In the first issue of Nüzi shijie,its initiator Ding Zuyin published two essays that encouraged the emergence of female writers. The first essay, entitled “An Ode tothe Women’s World,” draws a picture of the women’s world that the title of the magazine refers to. In this world, women can outperform men in three fields that were previously monopolized by men: the military world, the world of wandering heroes, and the world of letters. Accordingly, women can be brought up to become “nü junren 女軍人 (military women), nü youxia 女遊俠 (female wandering heroes), and n ü wenxue shi女文學士 (women of letters).” [18] Ding calls for women to participate in constructing this world because women’s self-development is essential to social progress and national salvation. Specifically, women of letters contribute to enlightening the public because literature can “open up one’s mind and cure ignorance.” [19] The other essay is a biography of the American female writer Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Ding praises her as a nü wenhao 女文豪 (heroic female writer), using her work’s influence on the achievement of the liberation of slaves as an example of how female writers can solve social problems and empower nations with their works. [20]

At the same time, female writers were warmly encouraged to contribute to Nüzi shijie and some other women’s magazines or newspapers. For example, in its first few issues of the year 1904, Nüzi shijie posted its “Call for Contributions on Women’s Learning (Reward Offered),” inviting readers to submit manuscripts in any generic form under one of the two titles: “Female China” and “Methods for Urgent Action to Save Women.” In the following issues, it published some of the selected submissions. In almost every issue, it posted a notice concerning its recruitment of investigators to report on the local development of women’s education. Moreover, it had two regular columns that exclusively published works from female writers: the poetry column “Yin hua ji 因花集 (Uniting Flowers)” and the essay column “Nüxue wencong女學文叢 (Essays on Women’s Learning).” The contributors that answered these calls were mostly female writers from within the education system: female teachers and students. These groups were the main readers of Nüzi shijieand also the main groups of people that magazine editors such as Ding successfully mobilized.

Some male authors also made contributions to feminist journals like Nüzi shijie by faking female authorship. Differently from Xu, who claimed his wife’s authorship, the others used feminine pen names instead, such as Zhou Zuoren’s 周作人 (1885-1967) pen name “Pingyun nüshi 萍雲女士 (Duckweed Cloud Lady),” and Luo Pu’s 羅普 (1876-1949) “Yuyi nüshi 羽衣女士 (Feathered Robe Lady).” When the number of female writers was still small and men’s monopoly in writing was hard to challenge, these fake female authors served as inspiring examples for their female readers.

Sometimes, this faked female authorship was also used as a selling point. For example, one of the major contributors to Nüzi shijie, Liu Yazi 柳亞子 (1887-1958) wrote several biographical stories about Chinese heroines including Nie Yinniang 聶隱娘, Hongxian 紅線, Liang Hongyu 梁紅玉under the pen name “Songling nüzi Pan Xiaohuang” 松陵女子潘小璜 (Pan Xiaohuang, a Girl from Songling). His writings shaped the fake author “Pan Xiaohuang” as such an attractive young female historian that Pan became not only a cultural icon for female readers but also a desirable woman for male readers. The publishing house for “her” writings, Xiaoshuo linshe, even received thousands of love letters to her from her readers. Reciprocally, the personal charm of this fake female author added to “her” works’ popularity and helped to disseminate the feminist ideas in these works. Therefore, apart from providing encouraging examples for aspiring female writers, in some cases, faking female authorship could also strategically turn the temporary rareness of female authors into an advantage through the creation of a “mysterious talented lady” image for the author and thus contribute to the work’s widespread popularity. Such cases as the success of Pan Xiaohuang paved the way for the rise of female writers.

Of the women: portraying nüjie (heroine) and nüjie (women’s sphere) as a strategy

Qingtian zhai is a story centered around a female revolutionary, Su Huameng, and the all-female investigation team that she leads. The story shapes these female characters—Su Huameng, Zhong Wenxiu 鐘文秀, and Wei Qunyuan 衛群媛—as model examples of the nüjie 女傑(heroine), and constructs an imagined “ nüjie 女界 (women’s sphere)” through the display of a new sisterhood among them. Such an emphasis on the female gender is another of Xu’s strategies to set role models for female readers.

The nüjie or nü haojie 女豪傑 (heroine) was a dominant type of ideal woman promoted by progressive intellectuals in the first decade of the twentieth century. A large number of biographical stories featuring both Western [21] and Chinese heroine exemplars were published in many feminist magazines. [22] Historical or fictional figures like Madame Roland (1754-1793), St. Joan of Arc (c. 1412-1431), Sophia Perovskaya (1853-1881), Hua Mulan 花木蘭, and others were set as exemplary heroines for Chinese women to emulate. Nüzi shijie was one of the major periodicals that promoted the concept of nüjie. It published a biography of Hua Mulan titled “Biography of the First Chinese Heroine and Female Soldier, Hua Mulan,” highly complimenting Hua Mulan’s martial skills and her patriotic commitment to her nation and people. Overall, in Nüzi shijie, the term nüjierefers to women who make contributions to national salvation, especially military women and martial heroines, which were the two types of heroines that dominated its “Biography” column.

Su Huameng is called a nüjieby Xu Nianci. In the story, she is mainly portrayed as a heroine who saves China with her displays of leadership in revolutionary movements. As a student at the modern women’s school, Zili nüxuexiao自立女學校 (Independence Women’s School), she is well-educated and very active in political activities. She is the female enforcement officer of the revolutionary political organization, Independence Society. At a meeting held by this organization to discuss how to deal with the potential unequal treaty between Qing China and the alliance of six foreign powers mentioned above, she successfully proposes to lead an all-female investigation team to Japan and Russia. She has also previously led a similar team and fulfilled a fruitful trip to investigate the local political societies and schools in many Chinese cities. These two activities have showcased her strong abilities in political participation and leadership. It can be inferred that in the unfinished part of the book, she is going to be the leader of more revolutionary activities and finally help to build China up as a powerful country.

Figure 4. A photo of “Jinghua nüxuexiao (Competition-Evolution Women’s School)” published in Nüzi shijie in 1905, vol. 2, no.2, p. 1. Source: Shanghai Library

As a nüjie, Su also prioritizes the national cause over her individual life. Su states the following view of marriage when she is as young as seven to eight years old: “One day I will be married to all the Chinese people.” [23] She is determined to devote her life to her nation and people rather than any individual man. From a feminist view, it is also a statement that rebels against the conventional social expectation of women and transforms the role of a woman from household wife to national citizen.

Another nüjiein the story is Su’s teammate, Zhong Wenxiu, who is brave enough to flee from her conservative family to seek a modern education and opportunities for political engagement. The author skillfully uses Zhong’s different life story to mirror the group of young women who are not as lucky as Su in gaining support from their families to pursue their life goals but must fight for the opportunity to become heroines through difficult struggles. As shown in her old-fashioned name, whose literal meaning is “collecting refinement and beauty,” Zhong was born into a traditional gentry family. She only received the new type of education that led to her enlightenment from a tutor when she was thirteen. Feeling much pressure from her family, she flees her home to pursue further studies at the Independence Women’s School in Shanghai. In this process, she constantly struggles with the tension between her filial love for her mother and her longing for freedom. For her, freedom does not just mean freeing herself from the control of her family but also a break from all of the traditional values, and especially those concerning female virtue. Her fights with her conservative mother exemplify the conflicts between different generations of women during the process of women’s liberation. Her intense inner struggles also epitomize the collision between the traditional and the new in a transitional and liminal age of revolutionary change, both for women and for the Chinese nation.

The part of the story about another of Su’s teammates, Wei Qunyuan, focuses on how heroines work together to construct a better world for women. It depicts a kind of ideal sisterhood that bonds women together in an imagined “ nüjie 女界 (women’s sphere).” The name Wei Qunyuan, which puns on the notion of “protecting fellow ladies,” implies her active role in building a collective community of women. The story offers little information about her but includes a brief account of her earlier investigation trip with Su. During the trip, they travel to many cities within the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River to investigate local schools and mobilize people to join the Independence Society. Their close collaboration exemplifies a new type of sisterhood that transcends biological ties and familial connections. Throughout the whole trip, Wei and Su act as one, for the sake of the same political goal: to promote modern education and social reform, including women’s liberation. The sisterhood between them also expands to include a larger group of women. During the trip, they receive positive responses from their audiences, with many traditional women eventually influenced by their progressive ideas.

The mobilization of more and more women leads to the construction of the imagined nüjie 女界 (women’s sphere) mentioned above. While the concept of nüjie女界has much semantic mobility and can be translated and interpreted in many other ways, as argued by Yun Zhang[24], this study adopts Yun Zhu’s definition of the term: “a nationwide community consisting of all of China’s female subjects.” [25] The entire story of Qingtian zhai presents community-building as a useful strategy for gathering collective power for political movements and social reform, such as forming political societies and uniting women to construct a “women’s sphere.” In Xu’s view, this imagined “women’s sphere” as a collective community is bonded by a sisterhood based on progressive feminist and political ideas as a “means of identification and mutual encouragement.” [26] In this sense, women’s liberation is incorporated into the mission of national salvation. Connecting women with the nation, he incorporates his call for the construction of a “women’s sphere” into his writing practice by telling the story of an all-female national salvation team which is formed by Su and her fellow female students and supported by a larger group of Chinese women.

Radical but Peaceful: Xu’s Political and Feminist Agendas

In Qingtian zhai,Xu puts forward his political and feminist agendas, both of which share the same paradoxical feature: they are radical but peaceful. In relation to his political agenda, Xu proposes revolution as the solution to China’s national crisis, a radical solution when compared with reform, but the forms of revolution presented in the novel are peaceful ones that avoid resorting to any violence. The finished part of the story focuses on the development of political organizations, modern schools, and revolutionary publications as support systems for revolution movements, thus reconciling the conflict between revolution and reform. As for his feminist agenda, while expressing strong support for women’s rights, as a male author, Xu pays more attention to women’s political engagement and patriotic commitment than to feminist issues per se. For example, the view of marriage presented in his Qingtian zhaiis more conservative than that featured in female author Wang Miaoru’s 王妙如 (1877-1903) Nüyu hua女獄花 (Flowers from the Women’s Hell) (1904). Following a peaceful agenda, he mitigates conflict between men and women by characterizing most male characters in the story as supporters of women. Qingtian zhaidifferentiates itself from other contemporaneous feminist political novels with its “radical but peaceful” proposals that adroitly balance future goals and current practical measures.

After the failure of the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), many progressive intellectuals turned to the idea of “revolution” as an alternative plan for national salvation. In 1903, with the widespread influence of the “Subao case” and the publication of Zou Rong’s 鄒容 (1885-1905) Geming jun 革命軍 (Revolutionary Army), “revolution” rose to become a popular concept in Chinese public discourse, [27] and it was imbued with “notions of historical necessity.” [28] “Revolution” was also promoted in many political novels, including Qingtian zhai. Xu refers to the “Subao case” in the story, arguing for the necessity of revolution as a solution to the national crisis. The “Subao case” exposes the Qing government’s hostile attitudes to freedom of speech and progressive ideas and its incompetence in dealing with public criticism. It also warns progressive writers of the risks of promoting revolution movements in their works. Qingtian zhaimirrors this reality with its narration of how foreign affairs officer Hu Weina 胡為那 (which puns on “misbehave”) responds to a telegraph calling for the rejection of the unequal treaty written jointly by a group of progressive-minded citizens in Shanghai. Taking the “Subao case” as a precedent, Officer Hu accuses the senders of the telegraph of being revolutionaries who are plotting revolts and decides to take punitive action against them in collaboration with the foreign governments that were party to the treaty. In this context, disappointed in the government and considering the risks, Xu proposes many peaceful forms of revolution.

In contrast with novels like Nüwa shi 女媧石 (The Stones of Goddess Nüwa) (1904) by Haitian du xiaozi 海天獨嘯子 (Lone Howler at the Horizon) and Nüyu huaby Wang Miaoru, in which female assassins feature as the protagonists, Qingtian zhaitells the story of Su Huameng, whose principal activity involves leading investigation teams on behalf of her organization rather than carrying out assassinations or killings. She does not resort to violence or confrontation but hopes to get her work done without attracting unwanted attention from the government. Su’s work is part of a revolutionary movement organized by the Independence Society. In the story, Xu includes the origins, goals, and development of this society, explaining that it supports two modern schools, Zili nanxiao 自立男校 (Independence Men’s School) and Independence Women’s School, and has set up branches in these schools. He also introduces the curricula used in these schools and gives a list of real-life newspapers and journals that promote revolutionary ideas, including “ Guomin xinwen 國民新聞 (Citizen News), Zhongyang gongbao 中央公報 (Central Official Newspaper), Zhejiang chao 浙江潮 (Zhejiang Tides), Jiangsu hansheng 江蘇漢聲 (Jiangsu Han Voice), Ziyou zhong自由鐘 (The Freedom Bell), and Geming jiguan革命機關 (Revolution Organization).” [29] Through these introductions, Xu presents an comprehensive support system for revolution movements consisting of political societies, modern education, and publications. The story provides down-to-earth instructions for readers to emulate and practice, such as reading the revolutionary journals listed. This approach contrasts sharply with that found in Nüwa shi, which tells dramatic fantasy stories such as one in which a female revolutionary party, “Hua xue dang 花血黨 (the Flowers’ (=women’s) Party of Blood),” uses advanced science technology to conduct mass assassinations. At the end of Chapter Four, through the medium of Su’s voice, Xu also discusses the relationship between reform and revolution from a well-balanced perspective. He gives priority to revolutionary movements, considering the urgency for national salvation, but also recognizes the importance of implementing reforms in fields such as education.

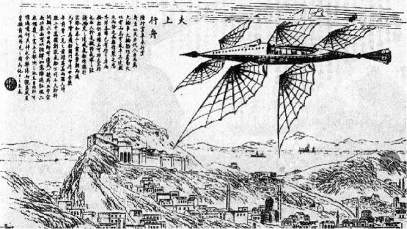

Figure 5. A portrait of Wang Miaoru attached to a 1904 version of Nüyu hua. Source: National Library of China

Xu’s feminist agenda is similarly paradoxical in nature. On the one hand, Xu shows his radical support for women’s rights and gender equality by having Su state that: “A filthy man is far worse than a pure woman…Though I am a woman, I will never be oppressed by men. It is best if all women resist any oppression from men just like me.” [30] In his own voice, he also encourages women to gain freedom, and enounces the wish that “Blossoms of freedom will abound in the women’s world and debts in the realm of love will be paid clearly all at once.” [31] On the other hand, like most male authors of his time, he subordinates his feminist proposals to the dominant nationalist discourse rather than focusing on women’s interests per se. His characterization of Su and her female companions as heroines is based on their commitment and contributions to the nation. The “women’s sphere” in his imagination is bonded by women’s shared political goal of national salvation.

Recent scholarship has taken a critical view of late Qing male authors’ feminist writings, with increasing attention being directed toward female authors. [32] As Yun Zhang points out, women’s issues in their own right only began to receive due attention with the rise of some female writers in the early twentieth century. [33] To explore how Xu Nianci as a male author deals with women’s issues differently from female authors, this study compares Qingtian zhaiwithfemale author Wang Miaoru’s Nüyu hua, with a focus on their respective views of marriage.

In Qingtian zhai,Xu emphasizes Su and her female companions’ political engagement while neglecting their personal lives and individual needs. Therefore, the topic of marriage is largely absent. There are two passing mentions of marriage: one is Su’s decision to marry all Chinese people instead of any man; the other is Zhong Wenxiu’s concerns about her future marriage, and she is depicted in a passive position. Zhong holds a pessimistic attitude towards marriage, thinking to herself about what awaits her if she is married to someone by her mother: if her future husband has received some form of progressive education, there might be some hope; if not, she will live a hard life forever. Fear of such a bleak scenario is one of the reasons for her to flee her home. In these two cases, women avoid or reject marriage without asking for sexual autonomy and freedom of marriage, one of the most important women’s rights among all of the feminist issues. If Su shows some autonomy in choosing not to marry, then Zhong’s concerns and her decision to flee show that Xu has put her in a weak position and only offers a peaceful and passive means of solution: escape.

The way in which Xu presents the problem of women’s marriage contrasts sharply with the two protagonists’ views of marriage in Nüyu hua.First, the revolutionary protagonist Sha Xuemei 沙雪梅 (whose name puns on “killing-blood beauty”) kills her abusive husband in a fight and lands in jail. It catalyzes her transformation into a radical revolutionary for women’s rights who calls for the killing of all men. Killing the husband in the novel is an extreme expression of female author Wang Miaoru’s hatred of gender oppression and men’s domination within marriage in Chinese society. The other female protagonist, Xu Pingquan 許平權 (whose name puns on “demanding equal rights”), is a reformer and has been engaged to a man for some time. She chooses not to marry him before completing feminist reforms and makes the decision to marry when the work is done. During the whole process, she shows a strong awareness of sexual autonomy and self-determination rights concerning marriage.

In addition to subordinating women’s issues to a nationalist agenda, Xu also mitigates conflict between men and women by characterizing most male characters in Qingtian zhai as supporters of women, which aligns with his peaceful feminist agenda: collaboration rather than confrontation. In the story, Su is raised by her uncle, Huang Yuying 黃毓英 (whose name puns on “the yellow race nurtures heroes”), an open-minded scholar who supports social reform and modern education. With his support, Su does not bind her feet. She can attend modern schools and access progressive publications at home. Her cousin, Huang Aizhong 黃愛種 (whose name puns on “the yellow people love their race”), expresses his admiration for her devotion to national salvation. Similarly, Zhong Wenxiu’s brother also supports Zhong’s pursuit of a modern education by persuading their mother to stop forcing Zhong back home and by providing Zhong with important financial support. The male members of the Independence Society also provide female members with equal opportunities to make proposals and conduct investigations.

In relation to both political and feminist agendas, Xu sets a radical goal but focuses more on realistic and practical procedures, making his plans paradoxically both radical and peaceful. Using the story of Su Huameng, Xu demonstrates that while revolution is the final solution, it is necessary to have comprehensive social reform as the support system for radical change. Based on his real-life experience of working in modern education, publishing, and political societies, he makes Qingtian zhai more like a guidebook for progressive readers than a fantasy story. As a male author, despite making radical calls for women’s rights, he subordinates feminist issues to a nationalist agenda. Compared with female authors, he does not pay enough attention to women’s interests per se, and the solutions he provides for women’s problems are peaceful ones that are far from radical: escape or collaborate.

Conclusion

This study has discussed the strategies used by Xu Nianci in the feminist utopian novel Qingtian zhaito promote his political and feminist ideas. He uses his imagination of China’s utopian future and depictions of highly metaphorical dreams about sleeping Chinese, dark prisons, and bloody massacres to criticize China’s backwardness, social injustices, and people’s numbness and desire for escapism in the face of national crisis. He appeals to the inactive Chinese to actively participate in efforts to achieve national salvation. As a strong supporter of women’s rights, he fakes female authorship for Qingtian zhaito provide an inspiring example to encourage women to become female writers. In the story, he portrays major female characters as female heroines and constructs a women’s sphere bonded by a sisterhood based on a shared political goal. This study also argues that Xu’s political and feminist agendas are radical but peaceful ones. He emphasizes that revolution is a necessary solution to the national crisis but gives most of the space in his story to peaceful reforms in political organizations, education, and publishing, important support systems for revolution. He makes radical arguments for women’s rights and encourages women to pursue freedom, but compared with some female authors, he pays insufficient attention to women’s interests per se. He subordinates women’s issues to a nationalist agenda and the solutions that he proposes to women’s problems, such as those concerning marriage, are peaceful ones such as escape. By characterizing most male characters as supporters of women, he mitigates the gender conflict between men and women and implicitly suggests collaboration as one of the peaceful methods of feminist revolution. His paradoxically radical and peaceful proposals are products of the transitional times of change for both the Chinese nation and for women during the last decade of the Qing dynasty. It was a time when revolution and reform efforts were being made simultaneously by progressive intellectuals and when national salvation was prioritized over other issues, including women’s liberation, by many of them. Men’s monopoly in feminist writing had only started to be challenged and feminist movements were experiencing the same collisions between the radical and the conservative, the old and the new. Qingtian zhaiwell represents the shaping power of these contesting ideas and serves as an instructive guidebook for progressive readers.

Xuezhao Li is a PhD candidate in Chinese Studies from the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Ohio State University. Her research interests include modern Chinese genre fiction and popular culture, literary translation in late Qing and early Republican China, and Digital Humanities. She has published a paper on the connection between literary translation and modern Chinese language reforms in the journal Comparative Literature & World Literature . Additionally, she has translated works by Chinese authors Wang Zengqi and Wang Tao, which have been featured on the MCLC (Modern Chinese Literature and Culture) Resource Center website and in the journal Renditions.

Bibliography

Chen, Jianhua. Geming de xiandaixing: Zhongguo geming huayu kaolun (The Modernity of Revolution: On Chinese Revolutionary Discourses). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2000.

Dooling, Amy D. Women’s Literary Feminism in Twentieth-century China . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Ding, Zuyin. “The Biography of Xu Nianci.” In Zeng Pu and the Writer Group from Mount Yu , edited by Shi Yin, 320-321. Shanghai: Shanghai wenhua chubanshe, 2001.

Ding, Zuyin, “The Ode toNüzi shijie.” Nüzi shijie(Women’s World) no. 1 (1904): 5-8.

Ding Zuyin, “The Biography of the Heroic Female Writer: Harriet Beecher,” Nüzi shijie (Women’s World) vol. 2, no. 1 (1905), 1-8.

Donghai Juewo (Xu Nianci). Qingtian zhai (Debts in the Realm of Love), Nüzi shijie(Women’s World) no. 1 (1904): 39-49.

Donghai Juewo (Xu Nianci). Qingtian zhai (Debts in the Realm of Love), Nüzi shijie(Women’s World) no. 3 (1904): 49-58.

Folkkema, Douwe. Perfect Worlds: Utopian Fiction in China and the West. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011.

Ishikawa, Yoshihiro. Zhongguo jindai lishi de biao yu li (On Stage and Backstage: Essays on the History of Modern China), translated by Yuan Guangquan. Beijing: Beijing University Press, 2015.

Juewo (Xu Nianci), “My Views of the Novel.” Xiaoshuolin (Forest of Fiction) no. 10 (1908): 1-8.

Jin, Guantao, and Liu Qingfeng. Guannian shiyanjiu: Zhongguo xiandai zhongyao zhengzhi shuyu de xingcheng (The History of Ideas: The Formation of Important Political Terms in Modern China). Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2008.

Judge, Joan. “Talent, Virtue, and the Nation: Chinese Nationalisms and Female Subjectivities in the Early Twentieth Century.” The American Historical Review 106, no. 3 (2001): 765-780. https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/106/3/765/54949?redirectedFrom=PDF

Liu, Lydia H., Rebecca E. Karl, and Dorothy Ko, (Editors). The Birth of Chinese Feminism: Essential Texts in Transnational Theory . New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Liang, Qichao, “Preface on the translation and publication of political novels.” In Yinbingshi heji(Collected Works from an Ice-Drinker's Studio), edited by Zhonghua shuju bianjibu. Vol. 2, 34-35. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989.

Liang Qichao, “A Warning of Being Carved up Like a Melon.” In Yinbingshi heji (Collected Works from an Ice-Drinker's Studio), edited by Zhonghua shuju bianjibu. Vol. 4, 19-42. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989.

Leese, Daniel. “‘Revolution’: Conceptualizing Political and Social Change in the Late Qing Dynasty.” Oriens Extremus 51 (2012): 25–61.

Qian, Nanxiu, Grace S. Fong, and Richard J. Smith. “Introduction: Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China.” In Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China, edited by Nanxiu Qian, Grace S. Fong, and Richard J. Smith, 1-28. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2008. https://brill.com/edcollbook/title/15101?language=en

Qian, Nanxiu. “The mother Nü Xuebao versus the daughter Nü Xuebao: Generational differences between 1898 and 1902 women reformers.” In Different Worlds of Discourse , edited by Nanxiu Qian, Grace Fong, and Richard Smith, 257-292. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2008.

Suvin, Darko. “Defining the Literary Genre of Utopia: Some Historical Semantics, Some Genealogy, a Proposal and a Plea.” Studies in the Literary Imagination , no. 6 (1973): 121-145. https://darkosuvin.com/1973/01/02/defining-the-literary-genre-of-utopia-some-historical-semantics-some-genology-a-proposal-and-a-plea-1973-9300-words/

Wagner, Rudolf G. “China ‘Asleep’ and ‘Awakening’: A Study in Conceptualizing Asymmetry and Coping with It.” Transcultural Studies , no.1 (2011): 4-139. https://heiup.uni-heidelberg.de/journals/index.php/transcultural/article/view/7315

Xia, Xiaohong, “The Great Diversity of Women Exemplars in China in Late Qing.” Frontiers of Literary Studies in China 3, (2009): 218–246.

Xia, Xiaohong. “Western Heroines in Late Qing Women's Journals: Meiji-Era Writings on ‘Women's Self-Help’ in China in China,” translated by Joshua A. Fogel. In Women and the Periodical Press in China's Long Twentieth Century: A Space of Their Own?, edited by Joan Judge, Barbara Mittler, and Michel Hockx, 236-254. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Yeh, Catherine Vance. The Chinese Political Novel: Migration of a World Genre . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Zhang, Longxi, “The Utopian Vision, East and West.” Utopian Studies , vol. 13, no. 1 (2002): 1-20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20718406

Zhang, Yun. Engendering the Woman Question: Men, Women, and Writing in China’s Early Periodical Press . Boston & Leiden: Brill, 2020. https://brill.com/display/title/38088?language=en

Zhu, Yun. Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017.

[1] For more about “the late Qing reform era (1895-1912)” and relevant scholarships, see Nanxiu Qian, Grace S. Fong, and Richard J. Smith, “Introduction: Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China,” in Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China, eds. Nanxiu Qian, Grace S. Fong, and Richard J. Smith (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2008), 1-28.

[2] Liang Qichao, “Preface on the Translation and Publication of Political Novels,” in Yinbingshi heji飲冰室合集 (Collected Works from an Ice-Drinker's Studio), ed. Zhonghua shuju bianjibu. Vol. 2 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989), 34-35. Translated by the author.

[3] For an overview of modern Chinese political novels, see Catherine Vance Yeh, The Chinese Political Novel: Migration of a World Genre (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 72-99.

[4] Juewo (Xu Nianci), “My Views of the Novel,” Xiaoshuolin (Forest of Fiction) no. 10 (1908), 2.

[5] Juewo (Xu Nianci), 8.

[6] Douwe Fokkema, Perfect Worlds: Utopian Fiction in China and the West (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011), 271.

[7] Zhang Longxi, “The Utopian Vision, East and West,” Utopian Studies, vol. 13, no. 1 (2002), 17.

[8] Donghai juewo (Xu Nianci), Qingtian zhai (Debts in the Realm of Love), Nüzi shijie (Women’s World) no. 1 (1904), 40.

[9] Darko Suvin, “Defining the Literary Genre of Utopia: Some Historical Semantics, Some Genealogy, a Proposal and a Plea,” Studies in the Literary Imagination , no. 6 (1973), 121.

[10] Huaxu is the name of a prehistoric Chinese civilization. The Huaxu people are the ancestors of the Huaxia 華夏people, who are the predecessors of the Han Chinese.

[11] The record is included in the collection Fa Yue jiaobing ji 法越交兵記 (Record of the French-Vietnamese Military Confrontation) (1886) edited by Sone Shōun 曾根嘯雲and Wang Tao 王韜. Rudolf G. Wagner, “China ‘Asleep’ and ‘Awakening’: A Study in Conceptualizing Asymmetry and Coping with It,” Transcultural Studies,no.1 (2011), 34.

[12] Liang Qichao, “A Warning of Being Carved up Like a Melon,” in Yinbingshi heji (Collected Works from an Ice-Drinker's Studio), ed. Zhonghua shuju bianjibu. Vol. 4 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989), 21, 42. For more about the origin of the “sleeping lion” metaphor, see Yoshihiro Ishikawa 石川禎浩, Zhongguo jindai lishi de biao yu li 中國近代歷史的表與里 (On Stage and Backstage: Essays on the History of Modern China), trans. Yuan Guangquan 袁廣泉 (Beijing: Beijing University Press, 2015), 9.

[13] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 43.

[14] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 45.

[15] Ding Zuyin, “The Biography of Xu Nianci,” in Zeng Pu ji yushan zuojia qun 曾樸及虞山作家群 (Zeng Pu and the Writer Group from Mount Yu), ed. Shi Yin (Shanghai: Shanghai wenhua chubanshe, 2001), 320.

[16] In the story, the narrator and his wife live in 1964, so the stories took place sixty years ago.

[17] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 40.

[18] Ding Zuyin, “The Ode toNüzi shijie,”Nüzi shijie(Women’s World), vol. 1, no. 1 (1904), 8.

[19] Ding Zuyin, 7.

[20] Ding Zuyin, “The Biography of the Heroic Female Writer: Harriet Beecher Stowe,” Nüzi shijie(Women’s World) vol.2, no. 1 (1905), 1-8.

[21] For more about Western women exemplars in late Qing publications, see Xia Xiaohong, “The Great Diversity of Women Exemplars in China in Late Qing,” Frontiers of Literary Studies in China3, (2009): 218–246; Xia Xiaohong, “Western Heroines in Late Qing Women’s Journals: Meiji-Era Writings on ‘Women's Self-Help’ in China in China,” trans. Joshua A. Fogel, in Women and the Periodical Press in China’s Long Twentieth Century: A Space of Their Own? eds. Joan Judge, Barbara Mittler, and Michel Hockx (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 236-254.

[22] Qian Nanxiu examines the rise of the concept of nüjiein the 1902-1903 Nüxuebao女學報(Journal of Women’s Learning), see Qian Nanxiu, “The Mother Nü xuebao versus the Daughter Nü xuebao : Generational Differences between 1898 and 1902 Women Reformers,” in Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China, eds. Nanxiu Qian, Grace S. Fong, and Richard J. Smith (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2008), 257-292.

[23] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 48.

[24] Yun Zhang, Engendering the Woman Question: Men, Women, and Writing in China’s Early Periodical Press (Boston & Leiden: Brill, 2020), 51-52.

[25] Yun Zhu, Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937 (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017), 9.

[26] Yun Zhu, 11.

[27] Jin Guantao and Liu Qingfeng carried out a quantitative analysis of references to “geming (revolution)” in Chinese public discourse between 1896 and 1911. Jin Guantao 金觀濤, and Liu Qingfeng 劉青峰, Guannian shiyanjiu: Zhongguo xiandai zhongyao zhengzhi shuyu de xingcheng 觀念史研究:中國現代重要政治術語的形成 (The History of Ideas: The Formation of Important Political Terms in Modern China) (Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2008).

[28] Daniel Leese, “‘Revolution’: Conceptualizing Political and Social Change in the Late Qing Dynasty,” Oriens Extremus 51 (2012), 45. For a genealogy of “revolution” discourse in modern China, see Chen Jianhua 陳建華, Geming de xiandaixing: Zhongguo geming huayu kaolun 革命的現代性:中國革命話語考論 (The Modernity of Revolution: On Chinese Revolutionary Discourses) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2000).

[29] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 47.

[30] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 48.

[31] Donghai juewo, Qingtian zhai, no. 1, 41.

[32] Amy D. Dooling, Women’s Literary Feminism in Twentieth-century China (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 36– 64; Joan Judge, “Talent, Virtue, and the Nation: Chinese Nationalisms and Female Subjectivities in the Early Twentieth Century,” The American Historical Review 106, no. 3 (2001), 765-780; Lydia H. Liu, Rebecca E. Karl, and Dorothy Ko, The Birth of Chinese Feminism: Essential Texts in Transnational Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 1-7 .

[33] Yun Zhang, 52.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.