Introduction

Seal carving (zhuanke, 篆刻) began to be perceived as a form of literati art since its active practice by Wen Peng (文彭) (1498–1573). It remained predominantly a male art form in pre-modern China. Even when carving the relatively soft soapstone preferred by the literati carvers, the process involves the use of a certain amount of muscular strength. However, the scarcity of female carvers should not simply be attributed to the physical requirements of this art form. Cultural factors played a more important role. Seal carving demands a relatively high level of literacy in archaic scripts. Few women had access to formal education and few could become members of the literati. Consequently, few women possessed the requisite skills allowing them to become adept at seal carving due to their difficulty in accessing philological and artistic knowledge.

Active around the turn of the Ming and Qing dynasties, Han Yuesu (韓約素) (fl. 1630s) was the first female carver to achieve widespread recognition and admiration. She was the concubine of Liang Zhi (梁袠) (fl. 1630s), who was often known by his courtesy name Qianqiu (千秋). Liang was a disciple of He Zhen (何震) (ca. 1530–1604), the founding master of the Anhui school of seal carving and, along with Wen Peng, one of the patriarchs of the literati engravers. Han was apparently trained by Liang, and she later became known for the high standard of her stone selection and the delicacy of her style, which can largely be attributed to the textual recounting of her artistic achievements by male members of the literati.

Only a handful of her works have survived to the present day, and almost all of the examples that remain are of dubious authenticity. These include stones and seal samples (images of stamped seals with red seal paste, often preserved in seal catalogs (yinpu, 印譜)). Due to archival limitations, this paper will not include an artistic analysis of her achievements in seal carving, verification of the authenticity of the few remaining examples of her work, or a historical overview of her life. Instead, it will examine seal images attributed to Han and try to gain a deeper understanding of why the literati wrote about her seals in a manner which was closely linked with female identity. The main objective of this paper is to understand how Han’s unique artistic image was created with the help of told stories, the stereotyping of her persona, and the fabrication of legends via a close reading of poetic and narrative portrayals of Han’s feminine image spanning the period from her contemporaneous 1630s up until the early 20 th century.

Han’s position in the history of seal carving

Han Yuesu appears in Zhou Lianggong’s (周亮工) (1612—1672) Biographies of Seal Carvers (yinren zhuan,印人傳), a prominent early Qing account of major artists and their styles and techniques. The text of the section of this work concerning Han is presented below.

Inscribed before the Seals by the Lady of Hairpin Pavilion (Han Yuesu)

Han Yuesu of the Hairpin Pavilion was the maid–concubine of Liang Qianqiu. Han Yuesu was a lady with a bright mind. She was married to Qianqiu in her youth and was able to read characters. She could play the ruan (a type of lute) and compose melodies; she also knew how to play the zither. She saw Qianqiu making seals. At first, she helped treat the carving stones. Once the stones were handled by her hands, they became as clear as jade. Then she studied seal scripts and could soon carve stones—inheriting much of Sir Liang’s style. However, she often felt sorry for her weak wrists and seldom carved stones for others. It never took less than several months for her to finish a seal. It was her nature to only enjoy carving fine steatite soapstone (dongshi, named after its tender, meat-jelly-like quality). When faced with a stone slightly inferior to dongshi, she would say, “Do you wish me to chisel the bones of mountains? Luckily, I was not born dull. Why do you play such a bad joke on me?” She was not fond of making large seals either. When a large stone was requested, she would again say, “While one hundred or even eighty pearls would have pressed my wrist too hard, how could I ever manage this? Never mind, here is my husband.” However, when one obtained a tiny seal from Hairpin Pavilion, one would think the large ones did nothing more than block one’s sight (meaning they were useless, unrefined blocks of stone). I entrusted [Liang] Danian (Qianqiu’s younger brother) with the acquisition of several seals—powder shadow and rouge fragrance still linger around the delicate seal scripts (zhuan)— which I treasure dearly. He was able to obtain one of hers; Du Chacun once aided Qianqiu, upon his demand, and inscribed a colophon on an image of Hairpin Pavilion. Hairpin Pavilion delightfully paid him back with a seal. All of them, still totaling less than ten, are included in this catalog. It suffices that Udumbara flowers open up only occasionally: how can there be pity? Wang Xiuwei, Yang Wanshu, and Liu Rushi were contemporaneous to Hairpin Pavilion. They all were known for their poetry, and gained fame by marrying into famous families and (by marrying) celebrated dignitaries. A frail woman such as Hairpin Pavilion, who was only adept at seals and married to an poor old man, had nothing to rely on. However, those who received tiny seals made by Hairpin Pavilion still treasure them to this day as if they were loose gold and broken jade. How incredible that Hairpin Pavilion was received like this! Alas, this is how as humble a skill as this can be passed down!

I used to collect all kinds of crystal, jade, rhinoceros horn, and steatite soapstone seals, and they always filled several tens of boxes. I used to handle them frequently. Only my deceased concubine could return each of them to their slots. If I ordered another to do it, the seals would be in a mess all day. Later, they all ended up in others’ collections. In Chang’an, I composed the poem, “Remembering Seals”:

(The poem will be quoted and translated when it is discussed in the final section of this paper.)

Seeing various seals by Hairpin Pavilion, I lament for my deceased concubine as if she had just passed away.

鈿閣女子圖章前

鈿閣韓約素,梁千秋之侍姬,慧心女子也。幼歸千秋,即能識字,能擘阮度曲,兼知琴。嘗見千秋作圖章,初為治石,石經其手,輒瑩如玉。次學篆,已遂能鐫,頗得梁氏傳。然自憐弱腕,不恆為人作,一章非歷歲月不能得。性惟喜鐫佳凍,以石之小遜於凍者往,輒曰:“欲儂鑿山骨耶?生幸不頑,奈何作此惡謔?”又不喜作巨章,以巨者往,又曰:“百八珠尚嫌壓腕,兒家詎勝此耶?無已,有家公在。”然得鈿閣小小章,覺它巨鋟,徒障人雙眸耳。餘倩大年得其三數章,粉影脂香猶繚繞小篆間,頗珍秘之。何次德得其一章,杜茶村曾應千秋命,為鈿閣題小照,鈿閣喜以一章報之,今並入譜,然終不滿十也。優缽羅花偶一示現足矣,夫何憾!與鈿閣同時者,為王修微、楊宛叔、柳如是,皆以詩稱,然實倚所歸名流巨公以取聲聞。鈿閣弱女子耳,僅工圖章,所歸又老寒士,無足為重,而得鈿閣小小圖章者,至今尚寶如散金碎璧,則鈿閣亦竟以此傳矣。嗟夫!一技之微亦足傳人如此哉!

予舊藏晶玉犀凍諸章,恆滿數十函,時時翻動。唯亡姬某能一一歸原所,命他人,竟日參差矣。後盡歸之他氏。在長安,作《憶圖章》詩:

……

見鈿閣諸章,痛亡姬如初歿也。 [1]

Zhou Lianggong’s record is the “authoritative” source of basic biographical information about Han as well as a repository of insights into her artistic achievements in the sense that later mentions of Han are nothing more than modifications of this piece. Zhou speaks very highly of Han’s achievements while severely criticizing Liang’s seals for their rigid conformity in imitation of his master, He Zhen. According to Zhou’s evaluation, Qianqiu was a much less elegant engraver than his younger brother, Danian, as Qianqiu would accept requests to engrave any phrase onto seals [2] and would take anyone’s order as long as satisfactory payment was made. As a matter of fact, Zhou even states that people thought Han’s seals were more precious than Qianqiu’s. [3] Apparently, Han’s works were hard to collect, as she made very few in the first place.

Zhou emphasizes Han’s physical weakness due to her female identity, but also depicts her as being witty and straightforward when interacting with the customers who placed orders with her and Liang. In the answers Han provided when asked to produce seals using inferior material or seals of enormous size, she used exaggerated contrasts to point out her unwillingness in both cases. In addition, Zhou uses relatively colloquial language and the Jiangnan accent (Jiangnan being an area associated with cultural, artistic, and commercial flourishing) to portray a lively female image, the Jiangnan accent often being stereotypically perceived as soft and feminine.

Zhou’s emphasis on Han’s femininity—her art and her way of speaking were both linked to this—and his emphasis on the paucity of her seals might reflect an intention by Zhou to promote the comparatively feminine and delicate style of seals that had been perfected by Han. Yet, that style was not necessarily the one that Zhou approved of the most. In the following sections, I will try to present a possible answer to why Zhou associated such a gender stereotype of delicacy with Han’s art. The commercial context of the late Ming and early Qing seal carvers, in which followers of Wen Peng and He Zhen competed fiercely for the financial and discursive upper hand, might help us to understand the reasoning that I will now present. [4] Zhou had already shown (or intentionally portrayed) Han’s commercial side and how smartly she used her female identity to help the business that she operated with Liang. In order to sell his seals, Liang Qianqiu tried to establish himself by bragging about his ability to replicate He Zhen’s seals. Zhou Lianggong deprecates Liang for his lack of originality. Given the fact that Han was popular and that she practiced in the same style as Liang, a fact which would probably trouble Liang, Liang had to come up with an explanation, and this was female identity and rarity. However, there are two reasons why I will not proceed with my discussion within the framework of commercial competition. First of all, Zhou does not expressly do so in his biographical accounts of Han and Liang. Secondly, too little data about Han remains to this day for us to say anything with certainty about the production and consumption of her seals other than literary representations that were inevitably influenced by each author’s respective agenda. Instead, by examining Zhou’s appraisal of Han and Liang, we can gain a better understanding of how artistic discourse was influenced by commercial incentives.

Divided assessments of authenticity

Liang Qianqiu studied with He Zhen and was able to make almost identical copies of He’s works. This particular artistic skill, however, did not meet with unanimous approval within the community of artists, connoisseurs, and the literati. This discrepancy possibly indicates the existence of competition between different artist circles, even though all framed their preferences in terms of artistic value. In this section, I will lay out the two conflicting opinions. Later, I will try to speculate how this conflict might inform us with respect to how artists of a certain school could possibly introduce individual innovation into a well-established style.

Being He’s disciple, Liang was acquainted with many of the literati within He’s circle. They recognized Liang’s talent in copying He’s seals, deeming his copies so perfect that they were indiscernible from the originals. In 1610, about six years after He’s death, Liang edited a seal catalog, Seals of Elegance (yinjun, 印雋). It includes 439 seals, mixing original creations by Liang with copies of He’s seals. It was an important “reprint” of He’s works at a time when forgeries of his seals, of uneven quality, abounded. Seals of Elegance preceded in time the seal catalogs of other disciples of He who were also known for copying their master. [5] The two authors of the prefaces to Seals of Elegance, Zhu Shilu (祝世祿) (1539–1610) [6] and Yu Anqi (俞安期) (dates unknown), were part of He’s close circle. They both stated clearly that Liang was able to make impeccable copies.

My old acquaintance Wu Wenzhong (Wu Bin (吳彬), a famous painter, who was He’s friend) brought along some seals carved by Liang Qianqiu of Guangling, mixed with some seals that [He] Zhuchen (He Zhen) had made. I could not tell them apart and long gasped in surprise. Now that we have Master Liang, Master He is not dead! (Zhu Shilu)

舊交吳文仲攜廣陵梁千秋所爲印章, 雜主臣所為者, 余不復能辨, 驚嘆不已。有梁生, 何生不死矣。(祝世祿) [7]

As for Liang Qianqiu’s craftsmanship in copying He Zhen, he does not miss more than a single hair. Without natural techniques and magical dexterity, how can he achieve this? Even Chu He’nan’s (Chu Suiliang’s (褚遂良)) copy of [Wang Xizhi’s 王羲之 calligraphy in] Orchid Pavilion does not achieve this level of resemblance. (Yu Anqi)

若千秋摹之(何震)之工,不爽毫髮, 自非化工神巧, 何以臻此。即褚河南之摹《蘭亭》,未見其酷肖若是。(俞安期) [8]

Zhu and Yu’s prefaces suggest how we should appreciate Liang’s facsimiles of his master’s examples. At least in the eyes of these critics, modern concepts related to fine art, such as originality and individual style, were not necessary criteria for the appraisal of artworks. The capability to replicate the master’s works and create new works in exactly the same style as the master —a handy skill in the workshop, one might imagine, if the master had received an overwhelming number of orders—was appreciated by the market and the literati critics. It also guaranteed the succession of the particular artistic lineage.

There is no doubt that Liang could replicate He’s works and create new works in He’s style that passed examination by even the best connoisseurs of his time. Zhu’s preface insinuates that Liang could easily have qualified as He’s ghost-carver. Given that He worked as a professional carver, it is very likely that he ran a workshop similar to those of professional painters of his time. Seals carved by Liang but signed by He were not authentic works created by He. However, if we understand He’s style as an artistic school or a brand of workshop, Liang’s carvings were nevertheless authentic.

Zhu and Yu’s prefaces suggest one way to appreciate the duplication of established artists’ styles. Imaginal authenticity in seal catalogs does not concern the materiality of the stone—a very good fake seal can reproduce the same image. A seal catalog produced using copied stones is comparable to reproductions created using modern technology. Seal catalogs preserve an authentic image of the original image. Seals were originally used to ensure the authentic identity of the seal owner, and this function depended on the image of the stone left on the paper. Even though most seals in the Ming and Qing dynasties no longer functioned purely as legal instruments, as they had done, for example, in the Qin and Han dynasties, the authenticity of images still mattered a great deal, outside of their legal applications and in the artistic world. Artists signed their works with seals to assure collectors of their authentic authorship; students of seal carving would refer to seal catalogs for examples of masters’ works to copy and imitate. It is in this sense that we should understand Zhu’s comment that Liang “revived” He, even though the practice of copying another’s work would be viewed today as forgery and infringement of copyright. Being able to produce works of art exactly like those of one’s master was an admirable artistic skill. Yu Anqi even compared Liang to Chu Suiliang, who was highly esteemed in Chinese calligraphic history for making a copy of Wang Xi’zhi’s “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering (蘭亭集序).”

In terms of artistic appraisal, Yu and Zhu represented those who were relatively conservative and valued the skills of artists who possessed the ability to copy their masters. In terms of market competition, we could also say that they were major collectors and supporters of He and would have loved to see imitations of He’s works gaining popularity. Zhou, on the other hand, belonged to another group of connoisseurs who valued innovation and individual expressiveness, and he severely criticized Liang’s imitation and duplication of He’s seals.

Among those seals that Qianqiu made based on his own inspiration, there were many good ones. However, those ones that were copies of Master He, such as “making efforts to eat more,” “drink heavily, read poetry,” “life in green mountains,” make people want to vomit upon a single glance.

蓋千秋自運頗有佳章,獨其摹何氏「努力加餐」、「痛飲讀騷」、「生涯青山」之類,令人望而欲嘔耳。 [9]

Zhou specifically pointed out that he disliked Liang’s imitation. Interestingly, Han Yuesu’s style should be seen as involving direct copying of Liang. Not only did Zhou state in his account of Han that “she inherited Liang’s style,” but other sources also imply that this point was very much the consensus among collectors. In the following section, I will study a seal carved by Liang in order to understand the continuity of style from He to Liang, and then to Han, before continuing to ponder the question of how Zhou’s narrative explained Han’s popularity despite his contempt for the mere copying of masters’ work.

Collectors’ confusion between Han Yuesu and Liang Qianqiu

It is highly likely that Liang ran his own studio as a workshop supported by his disciples and their families, a group that included his concubine Han Yuesu and his brother Danian (梁大年) (even though he eventually refused to comply with Liang’s outsourcing requests). [10] Even though Han joked, as Zhou recorded in Inscribed before the Seals by the Lady of Hairpin Pavilion , when presented with a huge stone, “Never mind, here is my husband [to fill the order],” there were probably examples of work that was allocated to herself or Liang based on the material, style, and content of the demanded seals. The following seal and its inscription support such an assumption. Sometimes even adept connoisseurs from periods not long after that of Liang and Han attribute Liang’s work to Han, suggesting that they believed Liang’s works could have been created by Han.

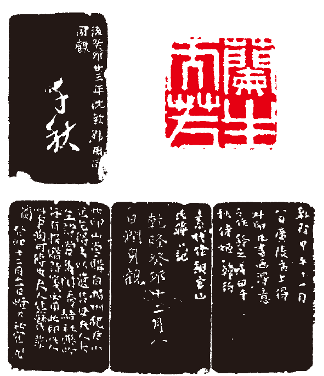

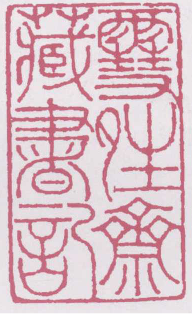

The following seal engraved by Liang is now held by Shanghai Museum. The seal reads “Orchid, born fragrant” (蘭生而芳). It bears an inscription by Jiang Ren (1743–1795) (蔣仁), suggesting that the seal as believed by some to be attributed to Han Yuesu.

Figure 1. A renowned seal engraver, Jiang, was one of the Eight Masters of Xiling (西泠八家), a group consisting of the most iconic and highly accomplished Qing seal engravers. [11] His side inscription reads as follows:

On the eighth day of the eleventh month, Jiawu year of the Qianlong reign (1774), I obtained this seal at a market in Guangling. I stamp it on whatever calligraphy or painting that I am satisfied with. Some say that Qianqiu’s concubine, Han Yuesu, made it on his behalf. Mountain Man of Tongguan, Jiang Ren, records.

乾隆甲午十一月八日,廣陵市上得此印,凡書畫得意之作鈐之。或曰千秋侍姬韓約素代作。銅官山民蔣仁記

Judging by the style and technique, this seal was indeed engraved by Liang. [12] The strokes are bold, with sharp angles at the beginning, ending, and turning points. More decisively, it was engraved mainly using the “single-carve technique” (dandao,單刀) without multiple “double carves” (shuangdao, 雙刀) and “cut carves” (qiedao,切刀). [13] Such a technique was first commonly practiced by He Zhen, and Liang learned it from his master. It contradicts Zhou’s remark that Han often took months to finish a seal, and differs from other seals attributed to Han, which are usually delicate and refined with smooth lines. If we take a closer look at some of Liang and He’s seals from his Seals of Elegance, especially those with the same fang (方) radical (Images 2, 3, and 4), we can see clearly that this seal was engraved by Liang in He’s style. The strokes are blunt at the beginning, uneven in width, and rough along the edges. Why did Jiang Ren still note that many attributed it to Han, a seemingly clear and obvious mistake? Other than Han’s popularity among collectors, Jiang’s remark, at least, reflected a relatively common opinion that their works could easily be confused. Put in another way, being trained by He, a carver known for copying his master, Han would have been good at copying Liang as well. This observation brings us back to the question I asked at the end of the last section: what did Zhou see in Han that went beyond the copying of Liang, other than the expression of her female identity, that made Zhou appreciate Han’s works? In other words, why did Zhou present the case of Han in a favorable way but the case of Liang in a negative way, while works created by these two carvers were so similar in style that many would fail to differentiate between them? In order to determine the answer, we need to take into account Zhou’s aesthetic preferences in relation to seal style.

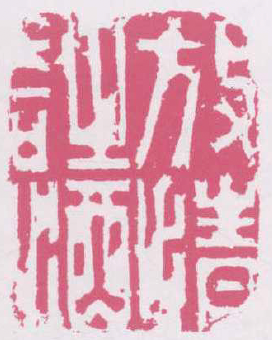

Figure 2. Liang Qianqiu, “Extraterrestrial immortal”, fangwai xian shi (方外仙史)

Figure 3. Liang Qianqiu, “Old man Hu from the west”, xifang lao Hu (西方老胡)

Figure 4. He Zhen, “Indulgence in poetry and wine”, fang qing shi jiu (放情詩酒)

Figure 5. Liang Qianqiu, “Zhu Wugong”, Zhu Wugong shi (祝無功氏)

Zhou Lianggong’s viewpoints on seal carving

Zhou Lianggong’s time witnessed changing aesthetic preferences in calligraphy, namely, increasing interest in stele scripts. Instead of learning solely from calligraphic sample books (tie 帖), carvers used rubbings of Han and Wei steles (bei 碑) that had been collected as samples for reference. Zhou’s own calligraphy was influenced by this trend, embodying epigraphic aesthetics, which were relatively more archaic, blunt, and forceful than the works of those who only copied sample books. [14] Zhou’s connoisseurship of seal carving was also heavily influenced by his studies of epigraphy and paleography.

Zhou’s admiration of He Zhen can shed light on his ideals regarding seal engraving. He was an expert in paleographical studies, which facilitated his archaic style of seal carving and was one of the major reasons why Zhou approved of him. Zhou wrote about this when appraising He’s seals in Biographies of Seal Carvers .

Guobo (Wen Peng) was devoted to the study of six scripts. Zhuchen (He Zhen) followed him and talked about seals with him without pause for days and nights. [He] often said: “Those who do not understand the essence of six scripts but can wave a carving knife like a writing brush—I don’t believe in such a thing.” For this, there are no mistaken strokes in Zhuchen’s seals. He mainly learned this from Guobo. [15]

國博究心六書,主臣印從之討論,盡日夜不休,常曰:「六書不能精義入神,而能驅刀如筆,吾不信也。」以故,主臣印無一訛筆,蓋得之國博居多。 [16]

Zhou’s emphasis on the importance of understanding the principles of character formation, archaic scripts, and calligraphy when appreciating He’s seals provides us with a clear understanding of Zhou’s criteria for good seals. For literati such as Zhou, the most important aspect of seal engraving was not skill in using knives per se, but the ability to use knives just like brushes so that the carver could write characters on stone. This requirement actually incorporates two phases of Chinese calligraphic practice: firstly, the more archaic philological tradition, in which most “written” characters were recorded for posterity as inscribed texts, such as in the cases of oracle bones, bronze inscriptions and stone steles and, secondly, the phase in which brushes were used to write characters and scripts of characters evolved due to changing writing habits of scribes. On the one hand, seal carvers engraved on hard surfaces, which was just like inscribing stone steles; on the other hand, they were using knives to write on stone surfaces, and needed to make the characters look natural, as if they had been written with brushes. Zhou’s approach emphasized brush-writing-like natural flow and, thus, self-expressiveness. As he states in the excerpt above, the first step in becoming a good carver is to know the principles of how characters were formed and how they evolved in script.

After understanding the structural rules of characters, the carver should understand how the characters are written on paper. Eventually, the carver should use a knife to recapture this natural flow on harder surfaces. Zhou stipulated this theory clearly when quoting Ming dynasty Anhui carver Jin Yifu (金一甫) in his comment on the latter’s seal catalog.

Jin Yifu…[was] devoted to the study of seal scripts. He once said that for seal carving, one had to understand the method of strokes (writing characters) first, and then the method of using knives….After one gets the essence of the ancient people’s legacy (in relation to) the methods of strokes, one can use a knife method to carve them.

金一甫……究心篆籀之學,嘗謂刻印必先明筆法,而後論刀法……筆法、章法得古人遺意矣,後以刀法運之。 [17]

“Carving like writing” is the key concept that Zhou wanted to promote here. In order to achieve this objective, it is crucial to be learned in paleography. When Zhou praised Han Yuesu, one aspect that he emphasized was Han’s knowledge in relation to writing characters. As Zhou depicted, Han could read and write characters before marrying Liang and studied seal scripts after their marriage as a pathway to seal carving practice.

Another important standard used by Zhou to discriminate between good carvings and bad ones was self-expressiveness. This standard can be understood as a natural development from “carving like writing.” If good calligraphy can manifest an artist’s individual character and personality, so should good seal carving. Zhou severely criticized Liang Qianqiu’s lack of individuality when comparing him to his brother, Liang Danian.

People always say that Qianqiu is better than Danian. I alone claim that Danian can make use of his own intentions. Qianqiu only copied Master He’s style and dared not change a bit. This is not worthy.

世人恒以千秋勝大年,予獨謂大年能運己意,千秋僅守何氏法,凜不敢變,不足貴也。 [18]

As mentioned above, the contrast in attitudes toward Liang Qianqiu’s seals between that of Zhou and those found in Yu Anqi and Zhu Shilu’s prefaces probably reflects competition between different schools and collector groups. Pre-modern readers of Zhou also noticed this possibility. Wei Xiceng (魏錫曾) (?—1882) defended Liang Qianqiu from the perspective of the collectors’ market.

Zhou Liyuan (Lianggong) criticizes Qianqiu much in his Biographies of Seal Carvers, because he asked for Liang’s works but did not get them. Zhou thus discredits him.

周櫟園《印人傳》於千秋多微詞,蓋求其作印不得,遂詆之爾。 [19]

One further issue is that if Zhou’s applied consistent standards in his assessment of seal carvers, Han Yuesu should rank not much higher than Liang Qianqiu in his estimation, since Han mainly copied Liang’s style, and since they probably collaborated as an artist’s studio. A reasonable inference would be that Zhou had several of Han’s seals and wanted to promote her, coming up with the idea of emphasizing her female identity to make claims about the rarity of her seals, which would eventually lead to an increase in their market value. Female identity was often linked with the scarcity of certain works in Zhou’s time. This association was true for seal carving and for other works of art. Li Wai-yee also describes this phenomenon in the literary world in the following words: “Loss, absence, erasure, and ephemerality, which often feature in stories about the tenuous transmission of women’s writings, are made more threatening by political disorder.” [20] The same can be said about female artists.

Zhou faced a situation similar to the one I am experiencing now: few authentic examples of Han’seals were available for scrutiny. However, with the help of a gender narrative, Zhou turned scarcity into high collectability. In the following section, I will look at some examples of seals that may have been Han’s, embarking on a careful analysis of how Zhou linked Han’s artistic style with the notion of femininity.

Gender stereotype and individual originality

In what ways did gender stereotypes influence appraisals of the originality and individuality displayed in Han’s seal carving? Zhou’s negative comments in relation to Liang Qianqiu may have been the result of personal issues, but he rightly points to the importance of personal features for creative artists. Han studied with Qianqiu and probably even worked as his collaborator and ghost-carver, so how did Han establish her personal characteristics in the history of seal carving? Delicacy, carefulness, neatness, fluidity, and other nouns often used to describe femininity were applied in relation of her seal art. Zhou linked a female stereotype—delicacy due to physical frailness—to the small seals with refined lines found in Han’s imitation of He Zhen and Liang Qianqiu.

In addition to Zhou’s record, there are a few poems from the Qing dynasty that express the literati’s evaluation of Han’s seals. I will quote two poems here.

The concubine of the Liang family best resonates with Liang,

And exhausts her delicate mindfulness in inches of worms and fish

(scripts).

Even if her husband were to be enfeoffed in the future,

He would not need to envy the gold in the size of the bucket. (Wu Qian)

梁家小婦最知音,方寸蟲魚竭巧心。

他日封侯祝夫婿,不須斗大羨黃金。(吳騫《論印絕句》)

[21]

Weak wrists were not made to carve large stones,

So said Yuesu from the Liang family before.

Palindrome texts, small seals: they pass delicate fingers;

Powder shadow and rouge fragrance: they absolutely deserve affection. (Ni

Yinyuan)

腕弱難勝巨石鐫,梁家約素說當年。

回文小篆經纖指,粉影脂香絕可憐。(倪印元《論印絕句》)

[22]

Apparently, both poets were influenced by Zhou Lianggong, and emphasize the delicacy of Han’s craftsmanship. In the eyes of these pre-modern seal engravers and the literati, her contribution involved the introduction of tidiness to the boldness of the He-Liang school.

I will introduce two seals, most likely created by Han’s delicate hands, to illustrate her style.

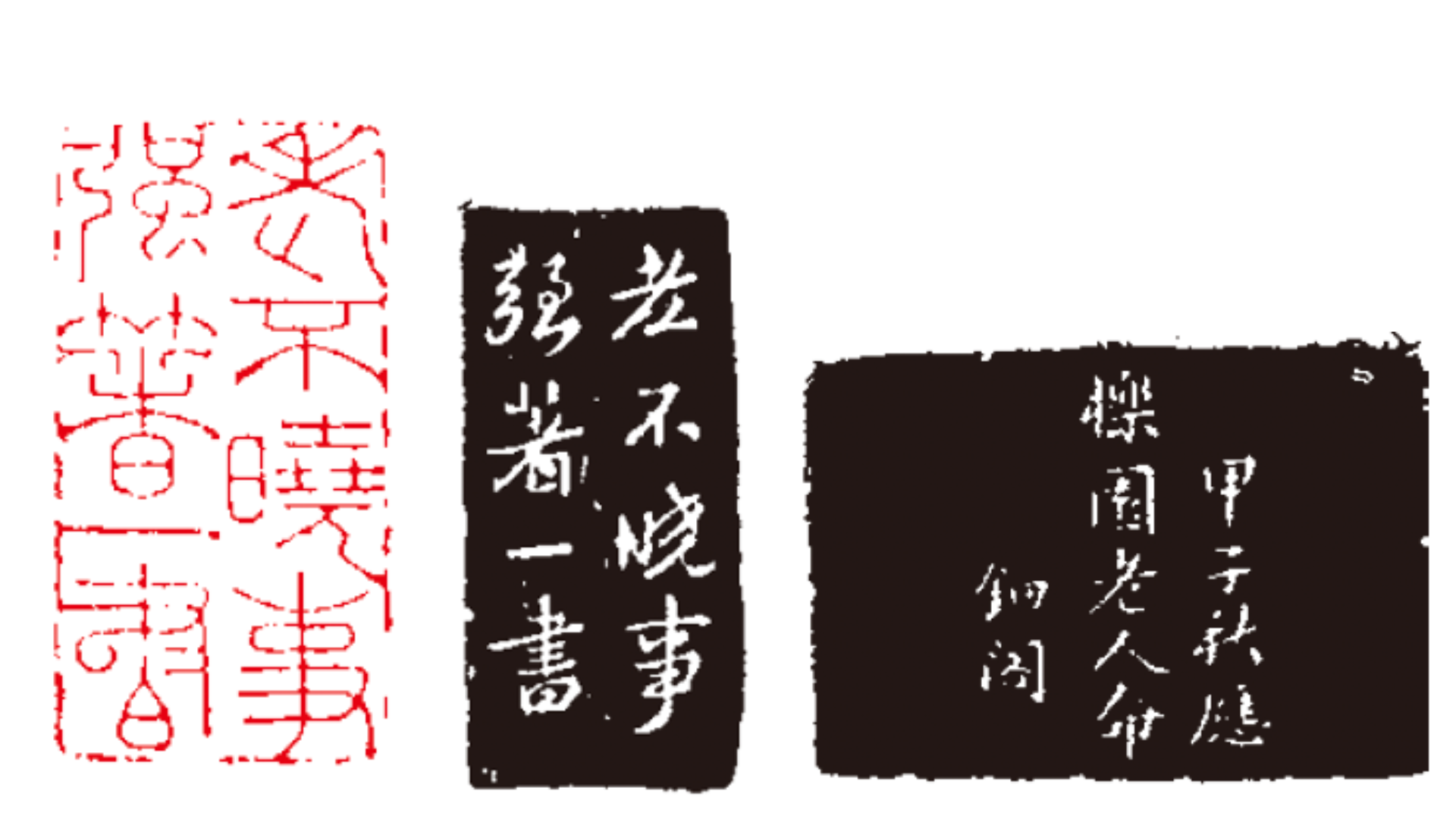

Figure 6. Han Yuesu, “Cutting not the tumbleweeds”, penghao bu jian (蓬蒿不剪), with inscription[23]

Figure 7. Han Yuesu, “Not knowing worldly affairs when old, but striving to write a book”, lao buxiao shi, qiang zhu yi shu (老不曉事強著一書), with inscription

The first seal, “Cutting not the tumbleweeds,” conforms to the He-Liang style with its rather free and bold arrangement of characters within the square. The strokes around the edges have blended into the void, breaking the limitation of the boundaries of the stone. Almost all of the intersecting strokes form right angles; some strokes still show a sharper beginning (e.g., the top left cao 屮 radical of hao 蒿) and ending (e.g., the tip of the vertical stroke in bu不). These features resemble the style of He Zhen and Liang Qianqiu. However, both edges of all of the strokes are evenly smooth, indicating that Han used multiple “cut carves” and “double carves” to smooth out the rough edges. Attention to detail and refinement of strokes, added to the bold visual confrontation created by the broken boundaries and wide (white) strokes, characterize Han’s personal stylistic modification.

The second seal, featuring characters in relief, is widely regarded as the most representative example of Han’s style. [24] The entire design of the characters is balanced and even. The width of each stroke is about the same. The rough edges have been carefully carved—there are places where the lines have been so repeatedly modified that they appear to be broken and dotted (e.g., the last character (shu,書)). Han probably used Liang’s imitation of He as a starting point, taking the emphasis on evenness, balance, and refinement to a higher level. In order to illustrate the development in style from He Zhen to Liang Qianqiu, and then to Han Yuesu, let us examine how Liang’s copies of He’s seals display increasing refinement and delicacy.

He Zhen made a seal known as “Hall of orchid-snow” (Image 8), and Liang made a copy of it (Image 9). Whenever Liang made a copy of his master’s work, he made the originally spontaneous and free composition more organized and evenly distributed. The two straight lines of the men(門) radical in He’s lan 蘭 are much more curved than those in Liang’s copy. Thus, He’s seal left more a larger void on the side and made the men (門) tighter and the jian (柬) radical wider.

Figure 8. He Zhen, “Hall of orchid-snow”, Lanxue tang (蘭雪堂)

Figure 9. Liang Qianqiu, “Hall of orchid-snow”, Lanxue tang (蘭雪堂)

Figure 10. Liang Qianqiu, “Seal for the book collection of the Studio of Cleared Snow”, Xueqing Zhai cangshu ji (雪甠齋藏書記)

Figure 11. Liang Qianqiu, “Mountain Studio of Turnip Rocks”, Luoshi shanfang (蘿石山房)

When Liang made his own relief seals (Images 10 and 11, for example), the lines and the distribution of void and solid space were more even than He’s. Liang also had more rounded shapes than did He. Liang still retained a certain amount of boldness and roughness, as the edges of the strokes were not perfectly smooth. We can imagine that Han also imitated Liang’s style, further developing the aesthetics of roundedness and smoothness—later labeled as female characteristic by Zhou Lianggong. She included more round shapes in order to smoothen the rigidness of square angles, and polished the edges more carefully, as shown in the seal “Not knowing worldly affairs when old, but striving to write a book” (Image 7).

Amorous history and commercial interest

Being the first detailed female seal engraver in history, Han Yuesu’s gender identity has, undoubtedly, contributed to how male intellectuals around her time, and Zhou Lianggong in particular, perceived her life experience and appreciated her art. While gender stereotypes related to frailness and delicacy might have been the product of male scholars’ imaginations, they nevertheless reshaped people’s perceptions of Han’s introduction of new personal features into the convention of seal carving within He Zhen’s and Liang Qianqiu’s lineage.

Zhou’s strategy was successful. The uniqueness of Han’s seal styles and the rarity of female artists in the market, which Zhou’s narrative joined together, led to an increase in commercial interest in her works. Jiang Ren’s side inscription (recording others’ false attribution of the seal to Han) exemplifies her popularity. Such a strategy continued to be used even centuries after her death in the world of popular literature.

Outside the circle of seal production and consumption, Han’s identity as a talented female (cainü, 才女) also attracted the appreciation of writers and publishers of commercial vernacular fiction. Many scholars have studied the commercial market for vernacular novels in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and female identity was a popular category that drove publishers to print anthologies, stories, and works of art produced by talented females. [25] For instance, the sudden expansion of Li Qingzhao’s oeuvre in the Ming dynasty can partially be attributed to commercial interest in famous female poets. [26] In Han’s case, her popularity as an artist, her identity as a female concubine, and commercial interest in talented females in the book market came together to be reflected in a “bizarre” manner in the character of one of the protagonists in a chapter of a sensually enticing vernacular novel, Amorous History of the Three Hundred Years of the Qing Dynasty (Qingchao sanbainian yanshi yanyi (清朝三百年艷史演義)) by Fei Zhiyuan (费只園, 1874–1931).

Fei was a somewhat obscure figure among the late Qing literati. He resided in Shanghai after the 1911 Revolution and engaged in education and the publication of newspapers and literary works. Fei was the grandson of Fei Danxu (費丹旭, 1802–1850), a renowned painter of female figures; this probably explains his interest and capability in presenting female images in literary form. The novel patches together historical anecdotes concerning famous concubines, such as Dong Xiaowan董小宛 and Liu Rushi柳如是, and includes references to many talented females. The part about Han Yuesu appears in the 58 th chapter, “Han Yuesu carves seals, good at choosing stones; Gu Erniang makes inkstones with fine inscriptions” (韓約素剝章工品石顧二娘製硯小題銘).

The chapter barely includes a storyline. Instead, in the first half, which relates to Han, Fei writes about the difficulty of acquiring Han’s seals, and in the second half, which relates to Gu, Fei catalogs several examples of Gu’s inscribed inkstones. The mention of both female artists does not add anything to the novel in terms of plot. However, it reveals the commercial interest in talented females. Including some anecdotes about two widely sought-after female artists would most likely have boosted sales of the novel since those who were interested in their artworks, whether or not they possessed examples of Gu’s inkstones or Han’s seals, would be interested in their stories.

The rarity of female artists and their products increased the latter’s market value. Fei was very aware of basic economics, stating clearly that the female identity of artists made their products more popular.

Those [intellectuals] who usually spread their reputation easily are the commoners, the monks, and especially the boudoir talents.

The term “boudoir talents” is erotic and romantic. They keep away from luxury and get rid of poverty either by marrying a good partner or serving a talented man. Isn’t it admirable? As for commoners and monks, one might still encounter them in the mountains, by the rivers, after tea, or after drinking (alcohol). After getting acquainted, one can still ask for their work. But for the boudoir talents, their gates are as secluded as the deep ocean; even if they were somehow talented, they would not easily show others. They are required to abide by the ethical code and to avoid contact with outsiders. Even if one obtained some [works by female talents] after much trouble, they would be nothing more than a few lines of poetry or a few strokes of drawing, still of dubious authenticity. If one desires something like a carved seal by Han Yuesu, it is even more difficult.

然大凡容易傳名的,一是布衣,一是方外,其一便是閨秀。

「閨秀」二字,是香艷的,屏除豪華,解脫寒儉,或半聯嘉耦,或得事才人,這不令人可羨嗎?但是布衣、方外,在山巔水涯茶餘酒後,還能徬佛相遇,推襟送抱,可以求他一點作品。那閨秀是門深似海,便有一二技藝,也不輕易示人,什麼守禮教呢,避嫌疑呢,便算輾轉得來,不過幾句詩,幾筆畫,還不知道真的假的。象韓約素的刓章品石,卻是難上又難。 [27]

Juxtaposing Han Yuesu in the novel’s chapter with Gu Erniang indicates the perception of Han as a sought-after commercial “brand”—they became representatives of the finest craftsmanship of their respective products. Dorothy Ko terms Gu Erniang as a “super-brand” of inkstones in her fabulous study of Chinese inkstones, The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China [28]. Even if Han was not a super-brand in the industry of seal carving like Gu Erniang was for inkstones, she was a sought-after artist, to say the least. The intentional attribution of crafted products, even some rather obvious forgeries, to female artistic brands demonstrates the commercial success of these “super-brands.” Mentions of Han in Fei Zhiyuan’s novel and Jiang Ren’s inscription on the seal perfectly illustrate the point that literary representation and art market activities worked in tandem to create a female super-brand. As I have discussed above, despite his expertise in seal carving, Jiang Ren made a rather obvious mistake, one which would not have been overlooked by today’s connoisseurs, in labeling attributing a work by Liang Qianqiu to Han. Jiang added “some say” when attributing the seal to Han, thereby displaying his disagreement with such attribution. Yet, he added the phrase to his inscription in order to accentuate the rarity of the seal. Intentional (or, at least, somehow intentional) misattribution reveals that the Han brand was superior to the “Liang’s Studio” brand in the collecting market, providing evidence that the commercial popularity of female artists turned an otherwise commonplace school of craftsmanship into a commercial super-brand that was celebrated beyond the scholarly/artistic community, i.e., among general consumers and wealthy families.

Fei Zhiyuan acknowledged the superiority of the “super-brand” of Han Yuesu over the more conventional brand of “Liang’s Studio,” the latter seen as merely having inherited the lineage (or patriline) of the scholarly school established by Wen Peng and He Zhen.

[Liang] Qianqiu sometimes asked Yuesu to ghost-carve for him. When she did so, she followed the He [Zhen] method strictly and never missed a touch. Those seals with a side inscription reading “Hairpin Pavilion” are, on the contrary, charming and gentle. They have apparently been made by female hands upon a single glance. Reviewers even ranked Han’s works higher than Qianqiu’s. How incredible is that!

千秋有時也令約素代刻,那代千秋刻的,是恪守何法,一絲不走。邊款署著「鈿閣」的,卻是風華旖旎,望而知為閨人手澤。品評的還說約素所作,勝過千秋,真是不可思議呢! [29]

Fei’s account follows Zhou Lianggonng’s assessment that the main innovation that Han contributed to the art of seal carving was her delicacy and additional refinement. The novelist’s judgment was most likely based on gender stereotypes instead of artistic appraisal because female sexuality was the theme and the selling point of his novel, as clearly shown in the title. Based on the simple information that Han was Liang’s concubine, Fei went further than Zhou’s narrative, subtly eroticizing their relationship by fantasizing about some unwarranted details.

Yuesu grew up in Baixia and had lived in the waterside [courtesan] quarters for several years. Qianqiu was famous; he was very close to Yang Longyou and Lan Tianshu. Sometimes they drank excessively among flowery ladies and watched the lovely young courtesan (Yuesu), who was almost too weak to carry the weight of her clothes.

這約素生長白下,曾在秦淮水榭里,住過幾年。千秋久負盛名,同楊龍友、藍田叔,俱稱莫逆。有時花間買醉,看這盈盈雛婢,弱不勝衣。 [30]

In the novel, their relationship starts as one of courtesan and patron, while Liang entertains himself and his male group with liquor and cabaret. They appreciate her body, which is covered in only light clothing. Their marriage is the result of a unilateral monetary transaction by Liang, and does not start in good faith.

Qianqiu always sighs: “isn’t it a pity that such a lovely girl ended up a prostitute?” Having long engaged in match-making, Longyou encourages Qianqiu to acquire her. Qianqiu’s pockets are deep at that time, and he takes out two hundred pieces of gold in order to purchase Yuesu. Qianqiu is obnoxious to Yuesu due to his advanced age. She repeatedly asks Longyou when Qianqiu will be appointed an official. Longyou continues to prevaricate. When she enters Qianqiu’s house, finding only worn-out brushes, left-over inksticks, loose brocade and patched silk, but nothing precious, she realizes that he is a poor literati. Seeing that he wears simple clothes and [scholar-style] headgear and shows no sign of the red robe and yarn cap [worn by officials], she knows that she had been tricked by Longyou. Luckily, Qianqiu teaches her the zither and (some) tunes. Gradually, she begins to feel how romantic it is that “Little Red sings low tunes while White Rock plays flutes.” [31]

千秋常嘆道:「若個可兒,淪落風塵,不是很可惜嗎?」龍友慣做撮合山,叫千秋移根而去。千秋橐金正在充牣,果以二百鈽購約素。約素憎千秋年老,每問龍友何日可除官?龍友輒漫應他。到得千秋寓里,只有些禿毫殘墨,零紈繼素,並無珍重品物,知道他是個塞(寒)士。又看他穿的是輕衫,戴的是幅巾,又沒有紅袍紗帽的氣象,才知道受龍友的賺了。幸虧千秋教他琴曲,漸漸有點領會「小紅低唱,白石吹簫」,這是何等的風流呢? [32]

In Fei’s depiction, Han was not quite satisfied with the marriage but changed her attitude after getting along with Liang in the context of scholarly entertainment. The eroticization of the scholar’s studio in the novel portrays a harmonious partnership between male and female. Such a harmonious partnership—strengthened by common artistic interests and infused with sexual nuance—became an ideal for many among the male literati. Such literati–concubine relationships as that of Han Yuesu appear in poems where seals are used as metaphors and stimuli for remembrance of the scholars’ concubines.

The seal as female metaphor: metaphoric objectification of women

While emphasizing that the female identity of the artists would have boosted the commercial success of their respective brands, we should also acknowledge that the commercial interests of early Qing scholar–artisans were often concealed behind certain cultural and artistic ideals. Within a studio, male scholar–artisans perceived their female partners as companions in their artistic pursuits. Scholars of literature and material culture have noticed that male scholars enjoyed what they viewed as an ideal arrangement involving artistic and emotional companionship with their wives and concubines in their domestic spaces and with courtesans in brothels, which were comparatively semi-public spaces. [33] The artworks which the concubines created became tokens by which the male literati remembered their female partners, especially after the concubines had passed away. When they composed poems remembering their deceased concubines, the artworks were then naturally transformed into metaphors, or what might be termed “object stimuli,” for their feelings. Their concubines became metaphoric objects (wuxiang物象) in their writings. In Zhou Lianggong’s account of Han Yuesu, for example, he ends the entry with a poem dedicated to his own concubine. The entire quotation can be found in the first section of this paper. I only quote the poem here.

“Remembering Seals”:

Receiving seal inscriptions, we constantly approach each other;

Low or high, each presents proper satisfaction.

[Reading] minute names—the overturned dipper is empty;

[Seeing] small seal scripts—I miss the spiral dragons.

Old steatite is sweet, like accumulated snow;

Astonishing ice is delicate, like layered grease.

The reds: refined as they jig-jog;

Smart intentions: enough to make people ponder.

《憶圖章》詩:

得款頻相就,低崇愜所宜,

微名空覆鬥,小篆憶盤螭。

凍老甜留雪,冰奇膩築脂。

紅兒參錯好,慧意足人思。”

Looking at samples of Han’s seals and writing about Han and Liang’s partnership triggered in Zhou a longing for his own concubine who, before her death, had been the only one who could assist Zhou in the arrangement of his seal collection. When Zhou was writing this poem, his seal collection was dispersed and his concubine died. This created a foundation upon which Zhou could place the seals and the concubine in tandem. The title implies a poetic equation between the female figure and the object of the seal—she was remembered as a seal, and the entire poem follows this motif in objectifying (in a neutral sense) his concubine. Whenever Zhou obtained a seal with an inscription, he would invite his concubine to study it with him. Whether the inscription was long or short, it was appropriate, meaning that it complemented the seal in perfect proportion. This opening couplet can also be read as a description of their ideal relationship: they always found a perfect way to be together, and the concubine always acted as he wished and she should. The name inscribed on the seal might have been that of his concubine, but it was no longer in use after she passed away. The intertangling strokes of the seal script resemble their loving interactions. The seal serves as a symbol of the concubine and their love. The poetic objectification of the lady as a seal is best exemplified in the third couplet, as it can easily be interpreted in two ways. One can read the couplet literally—that steatite soapstone is soft and oily. One can also read it metaphorically—that his concubine was sweet and refined in terms of the touch of her skin and her appearance. “The reds” in the final couplet (“the little reds,” more literally) also refers both to the seals, often pressed on paper in red paste, and his concubine.

Remembering a person after seeing related objects is probably a universal cliché in the context of poetic motifs, and in Chinese, it is called “seeing things, missing people” (duwu siren, 睹物思人). Metaphoric objectification of female carvers appears in poems, but beyond this, associating women with seals in poetry also, in reality, acknowledged the females in scholars’ studios and helped to open up spaces for them. The following poem by Chen Zhan (陳鳣) (1753–1817) appears to be a very simple one about the rarity of female artists, but it might also reveal Chen’s approval of the female role in artistic creation.

“Quatrain on Seal Carving”

Ladies in books there are: poems in paintings;

What about this saying—it is indeed interesting.

Further to seek iron pens in orchid boudoirs—

Before only Lady He, and later Concubine Han.

論印絕句

書中有女畫中詩,此意何如倒好嬉。

更向蘭閨求鐵筆,前惟何媛後翰姬。 [34]

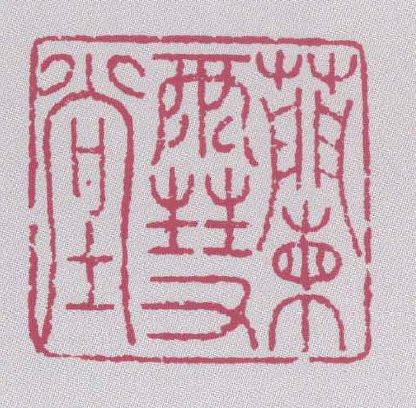

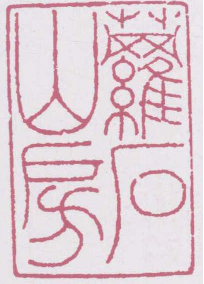

The opening line is an abbreviated quotation of a seal collectively used by Cai Han (蔡含) (1647–1686) and Jin Yue (金玥) (1656–?), “Ladies in books, poetry in paintings” (書中有女畫中有詩).

Figure 12. “Ladies in books, poetry in paintings”, shuzhong you nü, huazhong you shi (書中有女畫中有詩)

Cai and Jin were concubines of Mao Xiang (冒襄) (1611–1693, also known by his courtesy name, Mao Pijiang (冒闢疆)). Mao was famous for his literary and artistic talent as well as his romance with the famous courtesan lady Dong Xiaowan 董小宛(1623–1651) and his loyalty to the Ming court. After marrying Mao, Cai and Jin produced a number of birds-and-flowers and landscape paintings that bore this seal. [35] Chen Zhan referred to the fine paintings produced by this pair of artistic concubines as representative of female painters. The second line makes use of another seal related to a female artist, “Interesting” (haoxi,好嬉). Yuan dynasty literatus Wu Zixing (吾子行) used this seal when writing a colophon on a monochrome painting of bamboo created by Guan Daosheng (管道昇) (1262–1319), the wife of Zhao Mengfu’s (赵孟頫). In addition to the obvious allusion to a male artist’s comment on a female’s painting, this line invites readers to contemplate yet again the meaning of the first line and how interesting this phenomenon of concubine artmaking was. The inclusion of female writers in publications is like poetry complementing paintings. Poems are accessory to the paintings and are not necessary, but they make the paintings complete. Similarly, female writers were few in number, but they made books more fun. If we read this couplet allegorically, Chen hints that a harmonious male–female relationship in the studio should be just like those between female writers and poetry and between seals and paintings—the former supports and complements the latter in both cases. When Chen Zhan was looking for good female seal engravers and found only Lady He (He Yuxian (何玉仙), concubine of Shi Zhong (史忠), a Ming dynasty painter) and Han Yuesu, he was also looking for subordinate and talented female concubines who would aid their husbands in their careers. Chen Zhan’s poem uses the equation of seals and women from the “duwu siren” motif to symbolize and manifest the ideal supportive relationship between those of male and female gender (from a pre-modern standard, with the female supporting the male).

The male ideal of a supportive concubine with talent and shared artistic interests would also explain why, in the literary imagination of female figures, authors would make concubines artistic and artists erotic. In addition to the commercial incentive, discussed above, the underlying mentality was that there was a correspondence between collaborative gender roles and complementary components, i.e., between poems and seals on the one hand and paintings on the other.

The poetic objectification of concubines as seals certainly illustrates the unequal social and intellectual position of males and females in the pre-modern period. However, intertwined with market interest, it did, in fact, promote women’s engagement with the art of seal carving, a form that had been monopolized by males in Zhou Lianggong’s time. Han Yuesu’s pioneering contribution to the development of seal carving and collectors’ enthusiastic reception of her works led to more female seal engravers being able to explore and develop this form of art. During this historical process, commercial book printing—in particular, the publication of vernacular novels—and the poetic romanticization of male–female artistic collaboration in the studio further assisted in the development of this trend.

Concluding remarks

This paper focused on Han Yuesu, the earliest cataloged female seal engraver. As mentioned above, unfortunately, very few examples of her work remain. This paper also attempted to deepen our understanding of the history of seal carving and the role of women in its development. Zhou Lianggong’s biographical narrative, in which Han’s female identity is the most crucial aspect, became the proto-text used by people of later times to gain an understanding of this groundbreaking artist. According to Zhou, Han’s alleged tenderness and carefulness, associated with her femininity, added refinement to the school of He Zhen and Liang Qianqiu. The characteristics of Han’s art, with its innovative touches, at least in the eyes of certain critics, refreshed Liang’s studio, which had been confined to a style involving the meticulously copying of the works of his master. As a result, Han’s seals were extremely sought after by collectors and literati artists. Zhou’s portrayal of Han could very well have been commercially driven, but his strategy for popularizing Han, with its emphasis on her female identity, was a successful one. Even centuries later, Fei Zhiyuan utilized the same strategy, connecting female courtesans with female art in order to seek commercial success for his vernacular novel. In these literary representations, male literati perceived female engravers as a representation of the ideal male–female relationship within a scholar’s household and studio. Thus, in poetry, women engravers were poetically equated with seals.

As for the understanding of femininity in Han’s time, I would like to recapitulate that it did help female engravers to achieve commercial popularity due to their rarity. However, due to a lack of material evidence, a problem that Zhou Lianggong and I both faced is that we were unable to extract the actual female artist from the fabricated gendered narrative surrounding her. All I could try to do in this essay was to explore the role of gender narratives in the world of art and commerce during the late Ming and Qing dynasties and consider how such narratives might shed light upon the male ideal concerning gender relationships within the studios of the literati during this time in history.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my profound and sincere gratitude to Transnational Asia’s two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive suggestions and comments. I would also like to thank Amber Szymczyk for her editorial support.

Chao LING is an assistant professor in the Department of Chinese and History at the City University of Hong Kong.

[1] Zhou Liangong (周亮工), Yinren zhuan,Vol.1(印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, pp. 12b,13a. All English translations in this paper are mine unless otherwise noted.

[2] Traditionally, only names were made into seals. As literati began to practice seal carving, names of studios and, later, poetic lines gradually appeared. Zhou insists here that vulgar content should not be accepted.

[3] Zhou Liangong (周亮工), Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一),Gugong zhenben congkan(故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, pp. 8b.

[4] Study of the commercial aspect of literati art only began to gain momentum in recent years, even though earlier works have already touched upon this topic. James Cahill’s The Painter’s Practice: How Artists Lived and Worked in Traditional China (Columbia University Press, 1995) studied how painters dealt with payments and patronage. His Pictures for Use and Pleasure: Vernacular Painting in High Qing China (University of California Press, 2010) studies vernacular images in order to challenge the traditional prejudice against them. It also sheds light on the commercial aspect of art. Dorothy Ko’s critical study of Gu Erniang’s inkstones and their forgeries in The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China (University of Washington Press, 2017) clearly demonstrates how her female identity could help in the promotion of her products as a “super-brand.” More recently, Thomas Kelly has detailed the competitive environment in which Huizhou ink makers vied to gain market share in his The Inscription of Things: Writing and Materiality in Early Modern China (Columbia University Press, 2023).

[5] For example, Wu Zhong’s (吳忠) catalog was published in 1615; Wu Jiong (吳迥) published his in 1618; another famous catalog, Cheng Pu’s (程樸), did not appear until 1626. Zhou Lianggong praised Cheng Pu and his father Cheng Yuan (程原) for their immaculate replications of He Zhen’s seals. (See Zhou Liangong(周亮工),Yinren zhuan,Vol.1(印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, pp. 17b, 18a.)

[6] In the same preface, Zhu mentioned that he practiced seal carving with He Zhen, and that all his own seals were made by He Zhen.

[7] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選),Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, p. 448.

[8] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選),Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, p. 449.

[9] Zhou Liangong (周亮工),Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, pp. 8b. Kelly has a short discussion on Zhou Lianggong’s evaluations of Liang Qianqiu and Danian with regard to copying and originality in his paper. (pp. 34–37) See Thomas Kelly, “Impressions of loss: writing and memory in Biographies of Seal Carvers,” in Asia Major (2023) 3d ser. Vol. 36.1: 1–52.

[10] See Liang Danian’s entry in Zhou Lianggong’s Biographies of Seal Engravers . (Zhou Liangong (周亮工),Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, pp. 8b, 9a.) See also Kelly’s mention of Danian’s case in “Impressions of loss: writing and memory in Biographies of Seal Carvers,” p. 36.

[11] For a study of Jiang Ren, see Zhu Qi 朱琪, Zhenshui wuxiang: Jiang Ren yu qingdai zhepai zhuanke yanjiu (真水無香:蔣仁與清代浙派篆刻研究), Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin meishu chubanshe , 2018.

[12] For a discussion about Liang Qianqiu’s style of seal carving, see Qiao Zhongshi (喬中石), “Liang Qianqiu zhuanke chutan” (梁千秋篆刻初探), in Shufa Shangping, 2005 (5),pp. 47–53. See also, Zhao Hong (趙宏), “Zhuanying zhixiang xie ruanqu, ruowan kanpian zao shangu—mingmo nü zhuankejia Han Yuesu xiaokao”(篆影脂香協阮曲,弱腕偏堪“鑿山骨”——明末女篆刻家韓約素小考), in Shufa(書法), 2017(5), pp. 96–100. Zhao discusses this seal on p. 99.

[13] A “single carve” involves making a line into the stone with one continuous push of the knife, and is often marked by a sharper beginning and a blunt ending. One edge of the line is smooth, while the other is rough. “Double carves” consist of two single-carve lines, from each direction, to mark a stroke. Both edges are usually smooth. “Cut carves” are often used to make shorter lines which are eventually connected to make long lines, if needed, and to smooth out the edges of strokes.

[14] For an overview of the influence of epigraphic studies on Zhou’s calligraphy, see Zhu Tianshu (朱天曙), “Qingchu shibei fengqi zhong de Zhou Liangong shufa” (清初師碑風氣中的周亮工書法) in Shuhua shijie(書畫世界), 2009, Vol. 3, pp. 4—8. Very recently, a few English books about the influence of studies of stele inscriptions on literati art in the Qing dynasty have been published. See Michael Hatch, Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790—1840 (Penn State University Press, 2024) and Hye-shim Yi, Art by Literati: Calligraphic Carving in Middle Qing China (Cambria Press, 2024).

[15] The term “Six scripts” refers to traditional Chinese scholarship describing the principles behind the evolution of characters.

[16] Zhou Liangong (周亮工), Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, p. 6b.

[17] Zhou Liangong (周亮工), Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, p. 7a.

[18] Zhou Liangong (周亮工), Yinren zhuan,Vol.1 (印人傳·卷一), Gugong zhenben congkan (故宮珍本叢刊), Vol. 342, Hainan: Hainan chubanshe, 2000, p. 9a.

[19] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選),Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, pp. 890.

[20] Wai-yee Li, Women and National Trauma in Late Imperial Chinese Literature , Boston: Harvard University Asia Center, 2014, p. 317. She writes about Zhou Lianggong and his concubine in the same book. See pp. 319—331.

[21] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選), Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, pp. 865, 866.

[22] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選), Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, p. 856.

[23] This seal is in the personal collection of Xu Wuwen (徐無聞). See Zhao Hong (趙宏), “Zhuanying zhixiang xie ruanqu, ruowan kanpian zao shangu—mingmo nü zhuankejia Han Yuesu xiaokao”(篆影脂香協阮曲,弱腕偏堪“鑿山骨”——明末女篆刻家韓約素小考), in Shufa(書法), 2017(5), pp. 96–100. Zhao discusses this seal on p. 99.

[24] Debates still arise, however, regarding the authenticity of this seal. I have not had a chance to examine the stone, and thus hesitate in making a judgment. My tentative opinion is that this seal represents Han’s style even if it turns out to be an imitation. The forger would have referred to an authentic Han seal. See Zhao Hong (趙宏), “Zhuanying zhixiang xie ruanqu, ruowan kanpian zao shangu—mingmo nü zhuankejia Han Yuesu xiaokao”(篆影脂香協阮曲,弱腕偏堪“鑿山骨”——明末女篆刻家韓約素小考), in Shufa(書法), 2017(5), pp. 96–100. Zhao discusses this seal on p. 98. See also, Cai Mengchen (蔡孟宸), “Xiri pinlan bo yuanqu, jinzhao fu’an nong jinshi—lun nü zhuankejia Han Yuesu(昔日憑欄撥阮曲,今朝伏案弄金石——論女篆刻家韓約素), in Meixue yu yishu guanli yanjiusuo xuekan (美學與藝術管理研究所學刊), Vol. 7, 2007, pp. 45–66. Cai discusses this seal on pp. 57, 58.

[25] For studies of female artists’ role in Chinese culture, a few crucial books can be suggested. These include: Li Wai-yee, Women and National Trauma in Late Imperial Chinese Literature , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia. Center, 2014; Grace Fong, Nanxiu Qian, and Harriet Zurndorfer, eds., Beyond Tradition and Modernity: Gender, Genre, and Cosmopolitanism in Late Qing China, Brill, 2004; Nanxiu Qian, Grace Fong and Richard Smith, eds.,Different Worlds of Discourse: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China, Brill, 2008; Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-century China (Stanford University Press, 1994).

[26] For a study of Li Qingzhao, see Ronald Egan, The Burden of Female Talent: The Poet Li Qingzhao and Her History in China , Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2014; Ronald Egan, trans., The Works of Li Qingzhao, De Gruyter, 2019.

[27] Fei Zhiyuan, Qingchao sanbainian yanshi yanyi, in Peng Shilang (彭詩琅), ed., Zhongguo gudai yanshi daxi (中国古代艳史大系), Vol. 4, Beijing: Dazhong wenyi chubanshe, 1999, pp. 2389, 2390.

[28] Ko dedicates the fourth chapter of the book, “Beyond Suzhou: Gu Erniang the Super-Brand,” to inkstones made by Gu Erniang as well as others attributed to her. See Dorothy Ko, The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China , Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017.

[29] Fei Zhiyuan, Qingchao sanbainian yanshi yanyi, p. 2389.

[30] Fei Zhiyuan, Qingchao sanbainian yanshi yanyi, p. 2389.

[31] Little Red and White Rock can be understood as generic names for women and men, respectively. However, Fei alluded directly to the Southern Song poet Jiang Kui (姜夔) (1155—1209, his art name being Baishi daoren ) and his concubine Xiaohong in his famous line: “Xiaohong sings in a low voice and I play the flute” (小紅低唱我吹簫).

[32] Fei Zhiyuan, Qingchao sanbainian yanshi yanyi, p. 2389.

[33] It is beyond the scope of this paper, but see, for example, Wang Hongtai (王鸿泰), “Qinglou mingji yu qingyi shenghuo-mingqing jian de jinüyu wenren”(青楼名妓与情艺生活——明清间的妓女与文人), in Xiong Binzhen and Lü Miaofen (熊秉真、吕妙芬), eds., Lijiao yu qingyu: qian jindai zhonghuo wenhua Zhong de hou xiandaixing (礼教与情欲:前近代中国文化中的后/现代性), Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan jindaishi yanjiusuo , 1999, pp. 73—123; Huang Xiaofeng (黄小峰), “Muji fengliu: mingdai qinglou de kongjian yu tuxiang”(目击风流:明代青楼的空间与图像), in Meishu Daguan(美术大观), 2023, Vol. 8, pp. 12—22; Lara Blanchard, “A Scholar in the Company of Female Entertainers: Changing Notions of Integrity in Song to Ming Dynasty Painting,” in Nan Nü, Vol. 9 (2007), pp. 189—246.

[34] Han Tianheng (韓天衡), ed., Lidai yinxue lunwen xuan(歷代印學論文選), Hangzhou: Xiling yinshe chubanshe, 1999, p. 852.

[35] The Palace Museum in Beijing and the Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong, collect some of Cai’s paintings. See Sylvia Lee, ed., Her Distinguished Brushwork: An Exhibition Featuring Paintings by the Seventeenth-Century Artist Li Yin , Hong Kong: Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2017.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2024 Transnational Asia