Abstract

On September 19, 2017, a major earthquake struck Mexico City, leading to 369 confirmed deaths and over 6,000 injuries. After the collapse of a factory building holding Korean and Taiwanese-owned businesses—one of the deadliest sites during the earthquake—feminist activists led efforts to recover victims and to trace the historical antecedents of earthquake disasters in Mexico City. The earthquake therefore activated existing tensions regarding the social location of racialized migrants in Mexico and led to the enactment of transnational feminist solidarities across gender, class, and nationality. Treating disasters as moments in which the coordinates of belonging are renegotiated, this article examines how Koreans claim belonging in Mexico City despite ongoing processes of racialized exclusion that stereotype them as an exploitative labor force that embodies the worst aspects of global capitalism. Based on ethnographic and interview data, this article suggests that Korean migrants, though often invisible through the dominant lens of participatory citizenship, continue to survive, dwell, and make homes on shifting grounds.

Introduction

“In Mexico, everybody recounted to me his or her earthquake. … The earthquake came first. It became the indispensable condition to resume dialogue. I had to be initiated, informed, involved in what had happened. That’s the way I measured what took place. And I ask myself now, If the earthquake marked Mexicans to such an extent, if it invaded their lives, their memories, their minds, if it shook them up in such a way, and if every once in a while, one way or another, the earthquake comes back, what will its final mark be?”

—Elena Poniatowska, Nada, nadie: Las voces del temblor

On September 7, 2017, a magnitude 8.2 earthquake struck the southern coast of Mexico, killing nearly one hundred people and displacing thousands in the coastal states of Chiapas and Oaxaca. [1] Twelve days later, on September 19, 2017, another major earthquake shook densely populated central Mexico, leading to 369 confirmed deaths, over 6,000 injuries, and over two billion dollars in economic damage. [2] In an uncanny coincidence, the September 19, 2017 earthquake occurred thirty-two years to the day after the devastating Mexico City earthquake of 1985, which led to at least ten thousand deaths and caused severe damage to buildings, roads, and critical infrastructure across the metropolitan area. Indeed, that very morning, all of Mexico City had marched dutifully out of homes and workplaces to the soundtrack of the seismic alarm for the annual evacuation drill, which has the dual functions of emergency preparedness and remembrance of past disasters. I had participated in the evacuation drill with some of the South Korean residents of the hasuk, or boarding house, in which I had recently taken up residence in order to conduct in situ fieldwork with the Korean migrant community in Mexico City. While my primary interest had been in the transnational dimensions of this community—I had in mind the idea of studying Korean re-migration patterns and transborder networks across the Americas—the earthquakes forced me to grapple intimately with the exigencies of belonging, not only across transnational spaces but on the shifting and unstable grounds of Mexico City itself. Occurring early on during my fieldwork in Mexico, the haphazard capriciousness of the earthquakes and their unequally distributed consequences became an unavoidable frame not only for my interlocutors but for my own ethnographic praxis of interaction and reflection.

While this article is informed by eighteen months of extended fieldwork and sixty semi-structured interviews with self-identified Koreans living in Mexico, I focus particularly on the aftermath of the collapse of a factory building in the working-class neighborhood of Obrera, at the corner of Bolívar and Chimalpopoca streets. [3] One of the deadliest sites of the disaster, the building’s dramatic collapse was replayed across major national and international media as evidence of the earthquake’s deadly force. Search and rescue efforts were led by citizen volunteers, who rushed to the building to search for survivors and retrieve bodies in the absence of an effective government response. Among the twenty-one confirmed casualties were one South Korean man, four Taiwanese women, and one Taiwanese man (Armario 2017). The uneven violence of the earthquake brought attention to the labor conditions of migrant workers in the city, whose presence is too often marginalized and ignored. Thus, the building’s collapse and its aftermath converged with the shifting dynamics of international migration in Mexico more broadly, and in Mexico City in particular. As such, while leading to the enactment of transnational solidarities across gender, class, and race, the earthquake also activated existing tensions regarding the social location of racialized migrants in Mexico.

Though the majority of popular and scholarly attention characterizes Mexico as a source country of migrants rather than a recipient, it is nevertheless an increasingly important destination for migrants from Asia, Africa, and elsewhere in the Americas. The registered foreign population in Mexico almost tripled in the first twenty years of this century, from 492,617 in 2000 to 1,212,252 in 2020 (González Ormerod 2023). Net migration from Mexico to the United States fell to zero in 2009, with more migrants leaving than coming to the United States (Gonzalez-Barrera 2021). These shifts have led to the emergence of a binarized public discourse on migrant reception in Mexico. On the one hand, the hostile politics of transborder migration at the US-Mexico border has immobilized millions of migrants and refugees, primarily from Central and South America, who have transited Mexico in the hope of reaching the United States. In this case, Mexico has become an unexpected destination country, reshaping local spaces not only in border towns but in Mexico City as well. [4] On the other hand, Mexico City—especially the central neighborhoods of Condesa, Roma, and Juárez—has increasingly attracted young, affluent, primarily white professionals from Europe, the United States, and South America. These “lifestyle migrants,” to use Matthew Hayes’ (2018) term, have contributed to rising housing and living costs and exacerbated ongoing processes of gentrification in the central zones of Mexico City.

Koreans in Mexico City fit uneasily between the two poles of immobilized, class-disadvantaged, and racially marginalized migrants on the one hand, and privileged, class-advantaged, and primarily white migrants on the other. Indeed, while placing Korean migration within the broader framework of migratory shifts in Mexico, I argue that the 2017 earthquake revealed the instabilities and insufficiencies of this dyadic categorization. Certainly, some Korean migrants—particularly arriving on South Korean passports that afford better access to mobility and residence—are able to access class and capital resources that are unavailable to other migrant groups. At the same time, they are subject to processes of political and social exclusion that are linked specifically to their racialization as foreign threats, perpetually external to the nation. I analyze the controversy regarding the alleged presence of undocumented Central American workers in the basement of the collapsed building on the corner of Bolívar and Chimalpopoca streets. I argue that the linkages between these two migrant figures—the Central American as part of an invisible, abused labor force in the basement and the Asian as a “homo economicus” embodying the worst aspects of global capitalism—reveal the interconnected coordinates of migrant racialization in contemporary Mexico.

In making this claim, I am informed by a growing body of literature that has taken a relational approach to the study of Asian racialization in Mexico as well as in Latin America more broadly. Jason Oliver Chang (2017), for example, has shown how anti-Asian racism was linked to the formation of mestizaje, or racial mixing, as the dominant framework for race-making in Mexico. Chang argues that antichinismo, or the anti-Chinese movement in Mexico of the early twentieth century, was linked to the subsummation of Indigenous peoples under Mexican nationalism in the postrevolutionary era. Similarly, Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada and Federico Navarrete (2021) have pointed to the conditional politics of (un)desirability and the coercive regimes of mestizaje under which Japanese migrants and Mexicans of Japanese descent are uneasily incorporated into the nation. They write, “Mexican Japanese efforts at integration were hampered by the fact that their physical appearance, their surnames, and some of their cultural traditions did not fit into the dominant definition of mestizaje, defined along the narrow and brutally stratified axis that links feminized subjected Indigeneity to masculinized idealized ‘mestizo whiteness’.”

Treating disasters as moments in which the coordinates of belonging are renegotiated, this article examines how Koreans claim belonging in Mexico City despite ongoing processes of racialized exclusion. Writing about the aftermath of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Fukushima, Japan, Vivian Shaw (2017) has argued that “disaster…has historically troubled the boundaries of who is included in or excluded in the nation” (62). Similarly, I analyze the shifting grounds of inclusion/exclusion by considering how representations of Asian migrants become schematically linked to the figure of the Central American migrant, the dominant figure of “new” transit migration to Mexico. Such representations, however, rarely capture the complex claims of belonging enacted by Korean migrants. By centering the voices of “ghostly politics”—Alberto Vanolo’s (2017) term for the marginalized groups concealed by dominant representations of Mexican belonging—this article suggests that Korean migrants, though often invisible through the traditional lens of citizenship, continue to survive, dwell, and make homes on shifting grounds.

Multiple Migrations and Multiple Homes

Korean migrants first arrived in Mexico in 1905, when roughly one thousand laborers were contracted to work on henequén haciendas on the Yucatán Peninsula. The next significant wave of migration did not come until the late twentieth century. According to the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in 1997, only 2,168 South Korean nationals lived in Mexico. That number increased almost tenfold to 20,000 by 2001, before falling again. In 2017, when I began my research, 11,673 South Korean nationals lived in Mexico, approximately six thousand of them in Mexico City. It must be cautioned that the official number of South Korean citizens in Mexico does not necessarily provide an accurate reflection of the total population of ethnic Koreans living in Mexico. Such statistics are difficult to acquire because of the variety of citizenship and visa statuses represented among the community, as well as the prevalence of serial migration to and from Mexico. In a 2005 survey, only 54% of the respondents came directly from South Korea to Mexico—statistics that resonate with formal and informal interviews I conducted among Koreans in Mexico between 2016 and 2019 (Kim 2006). For example, I met and interviewed Korean re-migrants who held Argentine, Brazilian, or Mexican citizenship, as well as those who had entered the country on tourist visas and never regularized their status, which meant that they would not have been included in the official population statistics.

The multiple movements of Koreans in Latin America have led scholars such as Kyeyoung Park (2014) to describe them as a “rhizomatic diaspora,” which “indexes heterogeneous and multidirectional re-migration patterns that emerge across the diaspora, including ‘lateral’ migration (i.e., regional); chaotic and anachronistic migratory movement (i.e., unexpected and unforeseen moves); and return, repeat, and cyclic migration” (511). Such itinerant patterns reflect not only individual migratory decisions but also the broader exigencies of global neoliberal capitalism, which shape both opportunity as well as crisis, loss, and failure. In the case of Mexico, growth in the Korean population was linked not only to the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s that led to the restructuring of the South Korean economy, which precipitated an overall spike in outward migration from the peninsula, but the related economic crises in Argentina (1998-2002) and Brazil (1999), the two Latin American countries with the largest numbers of ethnic Koreans.

These itinerant migration patterns distinguish Koreans in Mexico from Korean migrants elsewhere in North America—namely the United States or Canada, where there are more significant settled communities. Because there are so many re-migrants in Mexico City, it is a common joke that they are not iminja (the Korean word for “immigrant,” which sounds like “two-migrant”) but rather sam-minja(“three-migrant) or sa-minja(“four-migrant”). Even if Mexico City is a relatively recent destination of choice, re-migrants carry the experiences of multiple migrations and, at times, multiple displacements. One interviewee, for example, located his family’s impetus to leave South Korea in the 1970s for South America in their initial dislocation from a hometown located in North Korea. Therefore, re-migrants often distinguish themselves and their journeys from those migrating on a temporary basis directly from South Korea, who tend to be transient white-collar professionals on limited-term job contracts, chujaewŏn(sojourning employees) sponsored by South Korean companies, or factory managers for multinational corporations.

Since the early 2000s, the clustering of Korean residents and businesses in the centrally located neighborhood of Zona Rosa has mapped a visible “Korean community” onto the urban landscape of Mexico City. Zona Rosa, or “The Pink Zone,” is the nation’s most prominent LGBTQ district, and has long been associated with a bohemian, cosmopolitan culture. Korean businessowners noted the benefits of setting up business in Zona Rosa, where leasing agencies were more accustomed to dealing with non-Mexicans, clientele more comfortable with non-Mexican cuisine, and neighbors more accepting of different customs, languages, and cultural practices. At the same time, however, the growing Korean presence in Zona Rosa has not been universally welcomed. For example, Time Out Mexicomagazine’s 2015 guide to the “secrets of the Korean neighborhood in Mexico City” alleged that there was a “red zone inside la Zona Rosa” and accused the “Korean mafia” of running prostitution rings within karaoke bars and controlling the area. Summarizing a prevailing stereotype of Koreans, the writer explains:

The Korean community, unlike the Chinese, is not as integrated into Mexican society. The Chinese have come to assimilate our culture without neglecting theirs; instead, Koreans and their children try not to lose their roots. Many refuse to speak in Spanish and do not have names in our language. [5]

In so doing, the author replicates many of the dominant assumptions about Koreans living in Mexico City. In addition to the association of Korean migrants with organized crime, it is presumed that Korean migrants have no interest in integration and that they keep Mexicans and other non-Koreans out by speaking only in Korean, refusing to translate Korean-language menus and signs into Spanish, and treating non-Koreans with hostility. Koreans, we are told, refuse to assimilate—by prioritizing homeland ties, choosing not to learn Spanish, and by keeping their Korean names.

Despite such stereotypes, I found that many of the ethnic Koreans living in Mexico, especially re-migrants from elsewhere in Latin America, arrived in Mexico already familiar with the Spanish language, had Spanish names, and possessed a desire to successfully integrate in their new homes. Because of the prevalence of small business ownership, my interviewees were particularly attuned to the cultural norms, trends, and interests of the residents of Mexico City. That is, despite popular assumptions of ethnic insularity, I found that many, if not most, Korean business owners targeted Mexican consumers and fretted about how to appeal more broadly to the Mexican public.

Furthermore, while many Korean migrants face significant language and cultural barriers—as they do in nearly every receiving country—they still laid claim to the city and developed a range of home-making practices in order to survive and thrive. To illustrate this, I would like to share the story of a woman that I called Kwŏnsanim, a title used for female church elders, in recognition of her leadership at the local Korean Presbyterian church. [6] I got to know Kwŏnsanim after I took up residence in her boarding house in Zona Rosa soon after my arrival in Mexico. A brisk woman in her mid-sixties, Kwŏnsanim’s route to Mexico City had involved multiple other locations in the Americas. She had left South Korea in the early 1980s with her husband, migrating first to Paraguay and later to multiple cities in Argentina. In 1999, she and her husband came to Mexico City, following her oldest son who had gained employment at a large South Korean company and hoping to take advantage of better opportunities for higher education for their two younger children. When her husband unexpectedly passed away in 2004, she began offering board to travelers and temporary visitors in her three-bedroom apartment in order to pay her rent; the business flourished, and when her next-door neighbors moved out, she rented out that apartment, expanding her business.

Kwŏnsanim was equipped with an extensive knowledge of the city and its many riddles, gained from many years of experience helping newcomers like me adjust to the tempo of life in Mexico City. She taught me how to best hail taxis on the street and navigate the confusing and circuitous routes followed by the peseros, the informal system of microbuses that crisscross Mexico City. She knew which stalls to visit and which to ignore as she haggled for the best prices for garlic, green onions, and dried chiles in the vast informal market of La Lagunilla. Kwŏnsanim was a storyteller: every stall, shop, coffee store, or restaurant contained an acquaintance with a dramatic history, an unexpected connection, or a lurid secret. At night, the boarding house became a space of conviviality, as guests sipped coffee and neighbors stopped by to watch television in the living room, swap stories, and share information—a place that began to feel like home despite the fact that the boarding house, by definition, was a temporary and transitory space for all of us who lived there.

Kwŏnsanim’s boarding house is a site that encapsulates some of the complexities and contradictions of the lives of Koreans in Mexico. A private dwelling turned into a thriving enterprise, the boarding house is an alternative domestic space in which the boundaries between public and private become blurred. For newcomers and guests, the boarding house provides not only shelter, food, and company, but knowledge, connection, and sociality. For one night, several months, or many years, the boarding house can become a home, a place where strangers might start to feel less strange. Importantly, the comforts of home are produced through the labor of women like Kwŏnsanim, who simultaneously played the role of caretaker, networker, cook, housekeeper, and savvy entrepreneur.

For Korean serial migrants, what counts as “home” is enmeshed in a complex set of power relations, cultural assumptions, and ideological fields. However, as this section has tried to show, migrants still express an array of attachments to Mexico City, and the economic and social investments they make have shaped the places in which they reside. In fact, many of my interlocutors described cultural familiarity, opportunity, and a sense of comfort in Mexico that speaks to the ways in which recent migrants claim belonging, even in locations of relatively brief residence. Reckoning with these different tempos and forms of home-making opens broader questions of who belongs to the space of the city—whose claims are made legible, and why.

Disaster and Belonging: Historical Legacies of Earthquakes in Mexico City

Disaster—in particular, earthquakes—has played an important role in twentieth century formations of national belonging in Mexico. In an uncanny coincidence, the September 19, 2017 earthquake occurred thirty-two years to the day after the devastating Mexico City earthquake of 1985. The 1985 earthquake led to at least five thousand deaths, displaced tens of thousands, and caused widespread damage to buildings, roads, and critical infrastructure across the metropolitan area. In the words of celebrated Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska (1988), the earthquake was a “collective epic event” that le[ft] a deep mark in the psychology of all Mexicans” (20) — a disaster that shook the very foundations of Mexico and deepened the cracks in the veneer of the national vision of progress put forth by the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI). The tepid government response to the disaster, characterized by corruption, inefficiency, and confusion, produced a vacuum into which ordinary citizens stepped up to lead rescue efforts, provide mutual aid, and organize responses to basic needs. Writers such as Poniatowska recorded the stories of ordinary Mexicans—the horizontal solidarity of the Mexican people, represented by the spontaneous unity of citizens’ aid—which contrasted starkly with the bumbling ineptitude and callous indifference of President Miguel de la Madrid (1982-1988) and his cadre of technocratic bureaucrats.

In the aftermath of the 1985 earthquake, new and strengthened popular urban movements, led by students, workers, and affected residents, demanded accountability and equitable reconstruction. Such efforts culminated perhaps most memorably in the Renovación Habitacional Popular (Popular Housing Renovation) program, in which President de la Madrid acquiesced to pressure to expropriate rental property damaged in the earthquake and reconstruct popular housing in the central zones of the city (Gilbert and Varley 1991, 47). Other social movements galvanized around rights and protections for laborers who had been disproportionately burdened by the earthquake. Garment workers, primarily women who toiled under hazardous labor conditions in unregistered factories, suffered particularly high death tolls; the collapse of multiple factory buildings, which had been shoddily constructed and maintained, killed over one thousand workers and left forty thousand unemployed. Growing from disaster relief response networks following the earthquake, the Sindicato de Costureras 19 de Septiembre (September 19 th Garment Workers Union)—named after the infamous date of the earthquake—was formed, becoming an important women-led independent union in one of Mexico’s largest industries (see Carrillo 1990).

This legacy of mutual aid, horizontal organization, and citizen action lives on today. As the writer Carlos Monsiváis (2005) argues, the earthquake was a major turning point in the modern history of the city that “pave[d] the way for the mentality that makes believable (sharable) a hitherto distant or unknown idea: that civil society leads, summons, and distributes solidarity.” That is, for Monsiváis and other Mexican intellectuals, the popular urban movements following the earthquake represented the flowering of an independent civil society that challenged the authoritarian structures of the PRI, the entrenched ruling political party. The common view of the 1985 earthquake, as urban scholar Diane Davis (2005) summarizes, is of a natural disaster that was “truly transformative of urban life, politics and society. The massive tremors themselves…empowered urban citizens to mobilize on their own behalf to challenge a corrupt and highly bureaucratized local government.”

Writing about the “mythology” of earthquakes, which links the response to the disasters with the “political arrival of the nation,” anthropologist Rihan Yeh (2018) recounts her memory of readingNothing, Nobody, Poniatowska’s classic account of the 1985 Mexico City earthquakes. She remembers being moved to tears by the story of Gisang Feng, a young Chinese Mexican man who volunteered to enter a collapsed building in search of victims. “It was there among the rubble,” Yeh describes, “that he [Feng] felt, for the first time, Mexican” (514). Yet, as Yeh writes in a footnote, Feng’s identification with Mexicanness was a detail that she herself had invented—a fiction whose resonance was perhaps linked to her own experience growing up Chinese in Mexico. Yeh’s testimony points to the powerful linkages between disaster and belonging in Mexico—in which even historically marginalized groups might imagine belonging via civic action.

Yeh’s account also raises the question of what it means to “feel” Mexican. Feeling, as performance scholar Jose Muñoz (2006) has taught us, is always connected to broader structures of inclusion, exclusion, and power. The earthquake necessitated a response, not only to the immediacy of the disaster itself but also to the urgent question of belonging in Mexico: how to claim the capital city, whose very name is metonymic of the nation, and how to be, one way or another, Mexican (see François 2023). This was a narrative of the nation that set itself against the state. After the 2017 earthquakes, as in 1985, activists and ordinary people rejected the state as a source of authority and aid, relying instead on horizontal bonds between ordinary citizens who had reached out their hands to provide the resources so desperately needed. That is, the common ground and solidarity brought about by the earthquakes became associated with “insurgent citizenship” (Holston 2008) and the full flowering of participatory democracy. But what about those individuals who, for various reasons, cannot access citizenship—for whom feeling Mexican, as in Yeh’s story, is an invented footnote? [7]

The September 19, 2017 Earthquake and Bolívar 168

The memory of 1985—as a turning point for civil society, people’s movements, and democracy—was re-lived, re-embodied, and re-membered simultaneously on September 19, 2017, as another major earthquake shook the city (see Allier Montaño 2018). The shadow of 1985 was inescapable in 2017, even for those who had not directly experienced the earlier earthquake or had arrived in the city decades later. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, amidst the wreckage of collapsed buildings, the city once again experienced a wellspring of mutual solidarity and aid. Thousands of volunteers rushed to the deadliest sites of the earthquake—an apartment complex on Álvaro Obregón Street, a primary school called Colegio Rébsamen, a factory located on Bolívar Street—to rescue victims trapped under the rubble. Armed with shovels, hard hats, and wheelbarrows, volunteers worked through the night to search for bodies. They formed human chains to clear out debris, passing broken pieces of concrete, shattered bricks, and crumpled metal rods away from the collapsed sites. In what would become the iconic symbol of the 2017 earthquake, volunteers would hold up fists to ask for silence—a gestural symbol repeated and replicated down the chain—if they thought they heard a human voice underneath the wreckage. Centros de acopios (collection centers) for damnificados—those affected by the earthquake—popped up on every street corner. I received hourly WhatsApp messages listing new sites that needed volunteers, and neighbors knocked on doors to request donation items urgently required by hospitals, welfare centers, and citizen aid groups.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, the lines between private and public, home and street, quickly became blurred. Tent encampments formed on the streets, as damnificados overflowed out of inadequate shelters. The damage was particularly severe in the central zones of the city located on the soft basin of Lake Texcoco, which had been painstakingly drained over centuries by Spanish colonial administrators. The lakebed is uniquely susceptible to liquefaction, when waterlogged sand is shaken into a fluid mass that cannot support the weight of buildings. A history of colonial exploitation, environmental degradation, and haphazard urbanization had left the metropolitan zone particularly precarious to seismic shaking.

In 2017, as in 1985, the swift action of ordinary citizens contrasted sharply with the government’s bumbling leadership, revealing the incompetence and impunity of the state under the governance of President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018). The political, economic, and social consequences of the earthquake reverberated throughout my time living in Mexico City and afterward, contributing to the defeat of the political dynasty of the PRI and the rise of a newly formed leftist party helmed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2018. For the progressive and activist-minded young people among my friends in Mexico City, a lasting result of the earthquake was a sense of rejuvenated civic duty and national belonging—a feeling of democratic potentiality that lingered long after the putative “end” of disaster and that linked volunteers with the historical legacy of popular sovereignty that had surged after 1985. The earthquake marked not only the “event” of a disaster but also a cyclical return of the people in a broader story of belonging to the city of Mexico and, by extension, to the nation.

But who was included in the imaginary of “the people” following the earthquake? I turn now to a discussion of the collective social response to the collapse of the factory building at Bolívar 168, at the intersection of Bolívar and Chimalpopoca Streets. Led by feminist activists organized as the Brigada Feminista (Feminist Brigade), over two hundred volunteers worked through the night to search for trapped victims. In addition to direct action, the Feminist Brigade made visible sedimented histories of gendered exploitation: between the 2017 earthquake and the devastating earthquake of 1985, when hundreds of female garment workers perished in prison-like sweatshops in the very same neighborhood of Obrera. That is, the collapsed building came to represent not only government inaction in the immediate moments after the earthquake, but a whole system of corruption and exploitative global capitalism in which women bore a heavier burden of risk.

When I visited the site on the afternoon of Sunday, September 24, five days after the earthquake, the rescue volunteers had been disbanded and bulldozers had already removed much of the heavy debris. Over the previous few days, heavy police activity and protests had made it impossible for me to approach the site. But now, the Bolívar 168 had been emptied and transformed into a makeshift memorial, a collectively built site of remembrance for the twenty-one people who had perished there.A remaining wall was emblazoned with the words, “Not one more buried due to corruption.” Torn pieces of fabric, beads, and other remnants were strewn about the lot, covered in the dust of pulverized cement and glass. I spotted a Korean-Spanish dictionary among the debris, its torn pages fluttering in the breeze. An altar had been built in one corner of the site, with candles and pieces of paper bearing the names of the deceased. I saw the names of the three Taiwanese workers. One note, bearing the name of Cinthia Yu Tang, said: “Sister my fight is for you, today I mourn you and I don’t forget you, I won’t allow you to be forgotten, you will be remembered.” As Satizábal and Melo Zurita (2021) propose in their analysis of Bolívar 168, such acts of remembrance link the local site of disaster to a relational and transnational politics of solidarity, as “the Brigada Feminista enacted and embodied territories of care, resistance, and possibilities” (270). That is, their actions demonstrated the power of feminist solidarity to expand the vision of care to include communities often ignored in dominant visions of “the people.”

Figure 1. Altars honoring victims at Bolívar 168. Photo by author.

At the same time, the disaster may have activated existing tensions regarding the social location of newly arrived migrants and the shifting coordinates of race and nation in Mexico. Not long after Korean and Taiwanese victims were located at Bolívar 168, a surprising rumor began to surface: that underneath the debris was a secret basement where undocumented Central American workers had worked and perished. The primary evidence for the existence of the basement was the presence of four Asian bodies that had been removed from the rubble. Expansión MX reported that “21 cadavers were brought out of the building, including Asian women, which has awakened the suspicion among activists that they were employed illegally.” [8] According to another online magazine, “More than a few members of the [Feminist] Brigade commented that Asian women had been rescued and, meanwhile, at least one Spanish-Korean dictionary had been found, which made them think that undocumented people worked in this factory.” [9] The rumors were exacerbated by the response of the government, which deployed police officers and armed soldiers to officially prevent further rescue efforts, claiming that all of the bodies had been removed from the site. After forty-eight hours of ceaseless volunteer search and rescue efforts accompanied by scant state assistance, the sudden appearance of the state was not welcome. Via protests and social media messaging, the Feminist Brigade opposed the local and federal government’s decision to prematurely raze the building site before search efforts had been exhausted.

A few days later, the volunteers of the Feminist Brigade posted a manifesto on their Facebook page condemning the Mexico City government for its inaction and its subsequent eagerness to raze the building despite rumors of the existence of the secret basement. The message concluded, “We recognize the structural violence of this patriarchal system that has resulted in death and impunity, because the deaths at Chimalpopoca and the other collapsed buildings are not a random accident [involving a] ‘natural disaster’; there are perpetrators and they have names and they are legal business entities.” But who were those perpetrators, and what were their names? In the following months, I watched closely as investigative journalists revealed that the building at Chimalpopoca had once been owned by the government, then sold, then rented out—despite its known structural deficiencies. But finding individual perpetrators—and bringing them to justice—proved to be more difficult than pointing out that systemic violence by the state, endemic corruption, and patriarchal oppression were ultimately responsible. Jaime Asquenazi, a Jewish immigrant from Argentina, was named as the landlord of the building. But he himself had perished in the collapse of the building, and it was unclear if he had known that the building was unsafe. Rumors that the bodies of Central Americans had been hidden or buried persisted for weeks, although the consular offices of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras denied that any of their citizens had been affected. [10] Because three companies in the building had been owned by Taiwanese and South Korean individuals, some accounts accused them of being corrupt managers who exploited non-Taiwanese and non-Korean workers. Still others pointed out that the Asian victims had been undocumented migrants with few legal rights. In other words, it was not easy to draw lines between perpetrators and victims. [11]

At Bolívar 168, Asian racial difference contributed to an ambivalent figuration marked by a heightened sense of inscrutability. On the one hand, feminist activists sought to draw transnational lines of solidarity among women garment workers, regardless of race, immigration status, or national origin. On the other hand, television broadcasts, newspaper articles, and social media conversations pointed to the discovery of Asian bodies in the rubble as proof of illicit labor and migration practices, thereby linking the presence of Asian labor to that which could not be seen: the abused Central American migrants in the basement that was never found. The rumors of the collapsed building at Bolívar 168 positioned Central Americans as the invisible, abused labor force in the basement and Koreans and Taiwanese as the owners and managers of the sweatshops that exploited them. That is, the intensifying scrutiny of Asian bodies at Bolívar 168 conjured the specter of Asian labor exploitation, which became linked to parallel anxieties regarding Central American migration to Mexico.

This relational pairing, I suggest, has broader hemispheric antecedents that shape how Korean migrants are understood in Mexico City. Scholars have long characterized Korean immigrants in the United States as an entrepreneurial “middleman minority” who are uniquely responsible for exacerbating interracial tensions, perhaps most infamously in the case of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. [12] Parallel characterizations abound in Latin America as well. For example, in her case study of the Korean garment industry in Argentina, Junyoung Verónica Kim (2017) suggests that Koreans are “singled out as the sole culprit of capitalist exploitation,” with Bolivian and Paraguayan workers seen as the exploited groups. In this racialized framing, “a problem of class or labor relations becomes transformed into an interracial and transcultural problem that lies outside the nation” (108). By inventing a narrative of super-exploitation between Asian capitalists and Central American labor, the case of Bolívar 168 echoes longstanding stereotypical depictions and reflects a hemispheric lexicon of Korean racialization that has taken on new significance in Mexico City.

Furthermore, the relational coordinates of race-making complicate the binary frameworks of “privileged” and “oppressed” migrations onto which the victims of Bolívar 168 were mapped. While scholars such as Aihwa Ong (2003) have contrasted the relative agency of transnational subjects with the exilic, abject subjectivity of diasporic populations, arguing for a “necessary conceptual distinction” (88) between the two, I suggest that the boundaries between transnational agency and diasporic dislocation might be more blurred. This disjuncture between transnational agency and diasporic abjection is echoed in the literature on transnational migration, which likewise often hinges on binaries between receiver and sender, core and periphery, First World and Third World, West and the Rest. In this Manichean transnational framework, Korean and Taiwanese migrants in Mexico become aligned either with the oppressive powers “from above” or the exploited peoples “from below.” However, because transnational migrants rarely fit neatly into such categories, attempts to classify unruly migrant lives can unfortunately reproduce longstanding racial stereotypes and tropes.

The reduction of complex migrant itineraries to legible binaries helps explain how anxieties over the figure of the Asian migrant become recurringly linked to the (de)legitimization of concern for the “problem” of Central American migrants in Mexico. Much as was the case during the 2017 earthquakes, during the global pandemic, whenever the question of anti-Asian racism or Asian Mexican belonging surfaced, I observed that the Central American migrant crisis frequently came up in response. [13] For example, in March 2021, one year after the WHO’s declaration of the global pandemic, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies recognized May 4, the day when the first Koreans set foot on Mexican soil in 1905, as the Day of the Korean Immigrant. [14] The announcement followed a similar recognition by the state of Yucatán, where the first Korean migrants arrived in 1905. The recognition of the figure of the Korean immigrant served primarily to mark the growing bilateral relationship between Mexico and South Korea as economic and political partners. The accompanying press release from the Chamber of Deputies emphasized growing South Korean foreign direct investment in Mexico as well as trading volume rather than the accomplishments and contributions of Korean migrants in Mexico. [15]

Part of a broader series of recognitions pursued by Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s administration—culminating especially in the official apology for the 1911 Torreon Massacre of over three hundred Chinese Mexicans two months later, in May 2021—some news media and opposition leaders interpreted the recognitions as “kowtowing” to the growing economic and political power of Asia, and especially of China. Legislator Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, for example, called the legislation authorizing the Day of the Korean Immigrant “ridiculous,” claiming that it represented AMLO’s capitulation to Asia: “We could also declare the day of soccer, which would be much more popular; the day of leisure, the day of the horse races, the day of the bread roll (bolillo)…” [16] Instead of recognizing Korean immigration, the lawmaker argued that more attention should be paid to the ongoing crisis of Central American migrants transiting Mexico in the hope of reaching the United States, which he characterized as a “true” problem worth combatting.

To be clear, I am not arguing in favor of or against the politics of representation or even disagreeing that the recognitions need to be understood within the broader contexts of transpacific capital. Instead, I am interested in how the apparatus of race becomes linked to who can claim belonging in Mexico. That is, in addition to the exigencies of global capital investment and tightening economic bonds between Asia and Latin America, recognition of Asian migration in Mexico became linked to the hemispheric consequences of United States empire, as Central American migrants fleeing violence and instability transit Mexico in the hope of reaching the United States. Therefore, rather than pitting Central American migrants and Korean migrants against each other—as if recognition of one group must come at the expense of the other—I suggest that examining both groups together reveals the broader logics that animate their differential inclusion and exclusion.

One way to do so, as Nicholas De Genova (2011) has argued, is to look beyond the dichotomization of inclusion and exclusion, focusing instead on the “process of inclusion through exclusion.” Emphasizing the interconnected coordinates of racialization reveals that Asian and Central American migrants might occupy different structural positions in the Mexican national imaginary, but they are simultaneously linked in their externalization from the nation—as exploiting and exploited labor, or as a recurring problem to be solved. Beyond seeing migration simply as an individual strategy of class mobility and reproduction—the quintessential immigrant search for a “better life”— analyzing the racialization of migrations—when, why, and how different migrant groups are subordinated or valorized— helps us understand the shifting boundaries of race, nation, and belonging within national, hemispheric, and global scenes of spectacle.

Conclusion

One of the victims at Bolívar 168 was a forty-one-year-old Korean man named Mr. Lee. The day after the earthquake, at one of many scenes of grieving across the city, I gathered with other members of the Korean community to mourn Mr. Lee’s passing. At his memorial service, after listening to testimonies from family members and friends, the head pastor of a local Korean Christian church gave a short sermon, pointing out that God’s will was often inscrutable from the perspective of human beings. He urged the mourners to trust in God, even in bewildering and painful circumstances, and to accept that all events, human and natural, were under God’s control. In the days following the earthquake, members of the community sprang into action to care for Mr. Lee’s family. A collection drive was started, and meals and childcare were offered to the grieving family. To give back to the broader community, youth groups organized and distributed boxed lunches for earthquake victims, while Korean churches ran donation drives of blankets, clothing, and medical supplies.

But such expressions of solidarity, even within the Korean community, were complicated by the inequalities of class and citizenship. One evening, not long after the earthquake, I found myself sipping instant coffee with a group of women in the boarding house. Unexpectedly, a heated debate arose when one woman commented that, since the earthquake, she had wanted to find an apartment in a neighborhood deemed “safer” from the risk of future quakes. Even if the rent were higher, she argued, Koreans should only occupy buildings that were certain not to be dangerous. Other women took exception to this argument, with one woman pointing out that some new buildings were damaged, while many older buildings were not; therefore, there was no human action capable of mitigating the risk. Natural disaster, this woman argued, affected all—rich and poor, men and women, Koreans and Mexicans—which meant that risk was beyond human control. This opinion was met with derisive laughter from the first woman. “Isn’t it the mother’s responsibility to ensure the safety of their families?” she asked. Her harsh tone was atypical for this gathering, and she quickly changed the subject, perhaps sensing the group’s unease.

In the aftermath of this natural disaster, it was social inequalities—the complex matrices of class, race, gender, and citizenship—that were thrown into sharp relief. Indeed, it became increasingly clear that we were not all equally exposed to the risks posed by natural disasters. Government efforts to reconnect electric lines and clear debris centered on the wealthiest districts, while piles of rubble blocked roads in poorer neighborhoods for months after the September earthquake. For example, in the working-class neighborhood of Iztapalapa, where nearly 35% homes had been damaged, the reconstruction of homes and critical infrastructure continued to be neglected by the government in 2021, four years after the earthquake. [17] In contrast, centrally located and cosmopolitan neighborhoods like Condesa and Roma Norte were cleaned up relatively quickly as Mexico City responded enthusiastically to a boom in international tourism.

Inside the walls of the boarding house where I lived, I watched with concern as a few thin spidery cracks that had appeared after the earthquake grew in size over time and the building’s gas and water were shut on and off for days at a time as they were allegedly being repaired. I watched neighbors begin to move out of the building, claiming that it might be structurally unsound. Almost daily, Kwŏnsanim complained about the emerging cracks in the walls and the dwindling number of guests at the boarding house, while in the same breath continuing to insist that we had nothing to fear if we had faith in God.

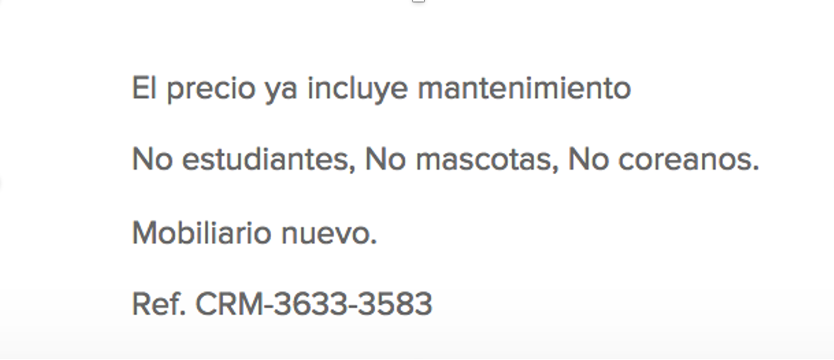

But two earthquakes and their aftershocks had shaken my trust in the building’s capacity to withstand another one. I began to search for alternative housing arrangements, which proved to be more challenging than I had expected. I was shocked to see, in online advertisements, lines that casually read, “We don’t accept students, Koreans, or dogs.”

Figure 2. Online advertisement for housing in Mexico City. “No students, no pets, no Koreans.”

I eventually chose another Korean boarding house in a newer building, this one catering to young professionals, tourists, and international students. I would be paying almost 30% more, but for a certified building with a doorman and other amenities. It was worth it, I reasoned, to be safe, to shield myself from what I saw as unacceptable risk. At the same time, as a Korean American graduate student and a US citizen, I was painfully aware of my own privilege, which had enabled me to quickly move from one boarding house to another, and I began to dread the conversation I would need to have with Kwŏnsanim about moving out of her hasuk.

A few nights later, Kwŏnsanim and I made instant ramen using the portable grill because the gas had once again been shut off. After we finished eating, she began to reminiscence about when she and her husband had bought this apartment, and how he had passed away shortly afterward. She considered it a miracle that the long-time renters next door had moved out just as she was seeking to expand her boarding house, making it possible for her to rent the neighboring apartment and increase her income. Kwŏnsanim complained again about the cracks in the walls, the unresponsive landlord, and the dwindling number of guests at the boarding house. She told me that her son and daughter were urging her to find safer accommodation, but that she did not want to leave her home—the apartment she had rented for over twenty years, the boarding house where she felt a sense of confidence in her ability to provide, and where she was happy and confident in her neighborhood and her lifestyle. This had all been a part of God’s plan, she told me, and as long as she felt the Holy Spirit dwelling in this place, she too would continue to dwell there. Kwŏnsanim’s determination to stay in her apartment suggests how Korean migrants fight to put down roots despite discrimination, marginalization, and other challenges—that is to say, even when thegrounds themselves shift beneath them. Here, at the limits of legibility and risk, belonging and exclusion, Kwŏnsanim told me defiantly that she was not going anywhere.

[1] The author gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Fulbright-García Robles Grant and the Center for Korean Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. This article was adapted from a previously published dissertation. See Lim, “Itinerant Belonging.”

[2] Investigative reporters have drawn attention to multiple omissions in the official statistics concerning casualties and injuries in the aftermath of the earthquake. See Ureste et al 2017.

[3] This article draws from eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork conducted primarily in Mexico City as well as the city of Mérida and its surrounding areas on the Yucatán Peninsula. The majority of the research took place between August 2017 and July 2018, although I also conducted pilot fieldwork activities in the summers of 2015 and 2016 as well as follow-up visits in October 2018, February-March 2019, and October 2019. I have used pseudonyms for the names of my interlocutors, except for individuals who are identified in their roles as public figures. In an effort to preserve anonymity, I have also changed small details—occupations, family relationships, places, or other potentially identifying information—when such details do not impact the argument or the individual’s broader narrative story.

[4] On the challenges faced by international migrants in Mexico City, see Faret et al 2021.

[5] n.a., “El barrio coreano de la Ciudad de Mexico.”

[6] As is the case throughout the Korean diaspora in the Américas, the Protestant Christian church is a significant organizer of community spaces and resources among Koreans in Mexico (Kwon, Kim and Warner 2001).

[7] As non-citizens, most Korean migrants do not have access to the realm of formal politics and are explicitly prohibited by Article 33 of the Mexican Constitution from “participating in any way in political affairs” (“los extranjeros no podrán de ninguna manera inmiscuirse en los asuntos politicos del país”). While written in response to a history of foreign incursion, Article 33 has mostly been deployed against non-Mexican participants in social movements such as the Zapatista insurrections in the 1990s and, more recently, in LGBT rights protests in various cities across the country (See Cieslik 2005). The South Korean government periodically publishes announcements in local Korean-language newspapers and online message boards reminding Koreans without Mexican citizenship to refrain from participating in even widely attended events such as Mexico City’s annual LGBT pride parade.

[8] Sánchez Morales, “Como en el 85, costureras quedaron bajo los escombros.”

[9] n.a. “Las dudas y la frustración que rodearon el caso Chimalpopoca.”

[10] Martínez, “La tragedia en la fábrica textil de Chimalpopoca.”

[11] For an account

of the uncertainties that remain regarding Bolívar 168, see Saldaña,

“Bolívar 168: Epílogo de una trampa mortal.”

[12] Bonacich and Light 1988 characterized Korean American immigrant entrepreneurs as prototypical middleman minorities, a characterization that has been complicated and nuanced by later studies, particularly those that focus on Black-Korean relations (C. Kim 2003; Abelmann and Lie 1997).

[13] For an analysis of Asian racialization in Mexico during the global pandemic, see Lim, “Racial Transmittances.”

[14] Hernández, “México celebrará Día del Inmigrante Coreano cada 4 de mayo.”

[15] See “Aprueba Cámara de Diputados declarar el 4 de mayo ‘Dia del Inmigrante Coreano’.”

[16] Salazar, “Pide Muñoz Ledo a diputados frenar ocurrencias y ridículo.”

[17] See n.a., “Iztapalapa aún sufre efectos del sismo 19-S.”

Bibliography

Abelmann, Nancy, and John Lie. 1997. Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Allier Montaño, Eugenia. 2018. “Memorias Imbricadas: Terremotos en México, 1985 y 2017.” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 80: 9–40.

Armario, Christine. 2017. “Migrant quest for Mexican dream cut short in quake.” https://apnews.com/65306736e3d846929582227596f9c390 .

Chang, Jason Oliver. 2017. Chino: Anti-Chinese Racism in Mexico, 1880-1940 . Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Cieslik, Thomas. 2005. “El problemático artículo 33 de la Constitución mexicana: la participación ciudadana de los extranjeros en los tiempos de la globalización.” In Pulsos de la modernidad: diálogos sobre la democracia actual , edited by Dejan Mihailovic and Marina González Martínez. Monterrey: ITESM, 141-160.

Davis, Diane. 2005. “Reverberations: Mexico City’s 1985 Earthquake and the Transformation of the Capital.” In The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster , edited by Lawrence J. Vale and Thomas J. Campanella, 255–81. New York: Oxford University Press.

De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1180–98.

Faret, Laurent, Andrea Paula González Cornejo, Jéssica Natalia Nájera Aguirre, and Itzel Abril Tinoco González. 2021. “The City under Constraint: International Migrants’ Challenges and Strategies to Access Urban Resources in Mexico City.” Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes 65 (7): 423–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12728 .

Fernández de Lara Harada, Jessica A. and Federico Navarrete. 2021.

“Mexican Japanese as Mestizos.” In “Unstable Identities in Search of

Home,” edited by Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada.

ASAP/J

.

https://asapjournal.com/node/unstable-identities-in-search-of-home-mexican-japanese-as-mestizos-federico-navarrete-and-jessica-a-fernandez-de-lara-harada/

.

François, Liesbeth. 2023. “Shaping the Right to the Megalopolis: Earthquake Crónicasin Mexico City.” In The Routledge Companion to Urban Literary Studies , edited by Lieven Ameel. New York: Routledge.

Gonzalez-Barrera, Amy. 2021. “Before COVID-19, more Mexicans came to the U.S. than left for Mexico for the first time in years.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/07/09/before-covid-19-more-mexicans-came-to-the-u-s-than-left-for-mexico-for-the-first-time-in-years/

González Ormerod, Alex. “A New Wave of Migration is Changing Mexico,” Americas Quarterly, December 7, 2023.

Hayes, Matthew. 2018. Gringolandia: Lifestyle Migration under Late Capitalism . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hernández, Nilsa. “México celebrará Día del Inmigrante Coreano cada 4 de mayo.” Milenio, April 29, 2021, https://www.milenio.com/politica/inmigrante-coreano-celebrara-4-mayo-mexico .

Kim, Claire Jean. 2003. Bitter Fruit: The Politics of Black-Korean Conflict in New York City . New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Kim, Hyong-ju. 2006. “La Experiencia Migratoria de La Nueva Comunidad Coreana En México.” Iberoamerica8(2): 1–25.

Kim, Junyoung Verónica. 2017. “Asia–Latin America as Method: The Global South Project and the Dislocation of the West.” Verge: Studies in Global Asias 3 (2): 97-117.

Kwon, Ho-Young, Kwang Chung Kim, and R. Stephen Warner, eds. 2001. Korean Americans and Their Religions: Pilgrims and Missionaries from a Different Shore . University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Light, Ivan and Edna Bonacich. 1988. Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Koreans in Los Angeles 1965-1982 . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lim, Rachel. 2021. “Itinerant Belonging: Korean Transnational Belonging to and from Mexico.” Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1947t9p8 .

Lim, Rachel. 2020. “Racial Transmittances: Hemispheric Viralities of Anti-Asian Racism and Resistance in Mexico.” Journal of Asian American Studies 23 (3): 441-457.

Martínez, Mercedes. “La tragedia en la fábrica textil de Chimalpopoca: estampa de nuestro México,” Sopitas.com,September 23, 2017, https://www.sopitas.com/noticias/chimalpopoca-fabrica-textileras-sismo/

Monsiváis, Carlos. 2005. No sin nosotros: Los días de terremoto, 1985-2005 . Mexico City: Ediciones Era.

n.a., “Aprueba Cámara de Diputados declarar el 4 de mayo ‘Dia del Inmigrante Coreano’,” Boletín de la Cámara de Diputados no. 611, March 2021. https://comunicacionnoticias.diputados.gob.mx/comunicacion/index.php/boletines/aprueba-camara-de-diputados-declarar-el-4-de-mayo-dia-del-inmigrante-coreano-#gsc.tab=0

n.a., “El barrio coreano de la Ciudad de Mexico,” Time Out Mexico , Jul 15 2015. https://www.timeoutmexico.mx/ciudad-de-mexico/que-hacer/el-barrio-coreano-del-df.

n.a., “Las dudas y la frustración que rodearon el caso Chimalpopoca,” Plumas Atómicas,September 23, 2017. https://plumasatomicas.com/explicandolanoticia/chimalpopoca-sotano-cisterna-trabajadoras/

n.a., “Iztapalapa aún sufre efectos del sismo 19-S,” El Universal , August 10, 2021. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/metropoli/cdmx/iztapalapa-aun-sufre-efectos-del-sismo-19-s/

Park, Kyeyoung. 2014. “A Rhizomatic Diaspora: Transnational Passage and the Sense of Place Among Koreans in Latin America.” Urban Anthropology 43 (4): 481-517.

Poniatowska, Elena. 1988. “The Earthquake: To Carlos Monsivais.” Oral History Review. 16 (1): 7-20.

Poniatowska, Elena. 1995. Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Mexico City Earthquake . Translated by Aurora Camacho de Schmidt and Arthur Schmidt. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Salazar, Claudia. “Pide Muñoz Ledo a diputados frenar ocurrencias y ridículo.” El Reforma, March 18, 2021, https://www.reforma.com/pide-munoz-ledo-a-diputados-frenar-ocurrencias-y-ridiculo/ar2146615?referer=--7d616165662f3a3a6262623b727a7a7279703b767a783a-- .

Saldaña, Nantzin. 2018. “Bolívar 168. Epílogo de una trampa mortal.” In 19 Edificios Como 19 Heridas: Por Qué el Sismo Nos Pegó Tan Fuerte. Edited by Alejandro Sánchez. Mexico City: Grijalbo/Penguin Random House. 227-244.

Satizábal, Paula and María de Lourdes Melo Zurita. 2021. “Bodies-holding bodies: The trembling of women’s territorio-cuerpo-tierra and the feminist responses to the earthquakes in Mexico City.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal . (6) 4-6: 267-289.

Sánchez Morales, Sofia. “Como en el 85, costureras quedaron bajo los escombros,” Expansión MX, September 22, 2017. https://expansion.mx/nacional/2017/09/22/como-en-el-85-costureras-quedaron-bajo-los-escombros .

Shapiro, Michael J. 1994. “Moral Geographies and the Ethics of Post-Sovereignty.” Public Culture6(3): 479–502.

Shaw, Vivian. 2017. “‘We Are Already Living Together’: Race, Collective Struggle, and the Reawakened Nation in Post-3/11 Japan.” In Precarious Belongings: Affect and Nationalism in Asia, edited by Chih-ming Wang, Daniel Pei Siong Goh, and Adrian Vickers. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ureste, Manuel, Tania L. Montalvo, Nadia Roldán and Omar Bobadilla. “#MapaContraelOlvido: ¿En dónde murió cada víctima del 19S en CDMX?” October 5, 2017. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2017/10/mapa-donde-murio-victima-del-19s-autoridades

Vanolo, Alberto. 2017. City Branding: The Ghostly Politics of Representation in Globalising Cities . York, NY: Routledge.

Yeh, Rihan. 2018. “2017: ‘Mexicano, México Te Necesita.’” In 1968-2018: Historia Colectiva de Medio Siglo , edited by Claudio Lomnitz. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2024 Transnational Asia