Abstract

In his book, Mapping China and Managing the World, Richard J. Smith offers an explanation for the “staying power of divination in China,” which “both embodied and reflected many of the most fundamental features of traditional Chinese civilization.” Although it always had a certain heterodox potential, divination “was not fundamentally a countercultural phenomenon.” Rather, enjoying abundant classical sanction and an extremely long history, “Chinese mantic practices followed the main contours of traditional Chinese thought.”

This article aims to add support to Smith’s argument, albeit from a perspective that fluidly trespasses the boundaries between the “heterodox potential” of divination and the “main contours of traditional Chinese thought.” Through examining mantic practices and theories recorded in a specific group of literary texts, this article argues that divination was a significant, if not indispensable, component in the self-fashioning of certain iconoclastic intellectuals, men and women, from the Wei-Jin 魏晉 (220–420) period to the late Qing 清 (1644–1911) dynasty in China, and from the Heian 平安 (794–1185) period to the Edo 江户/Tokugawa 徳川 (1603–1868) period in Japan.

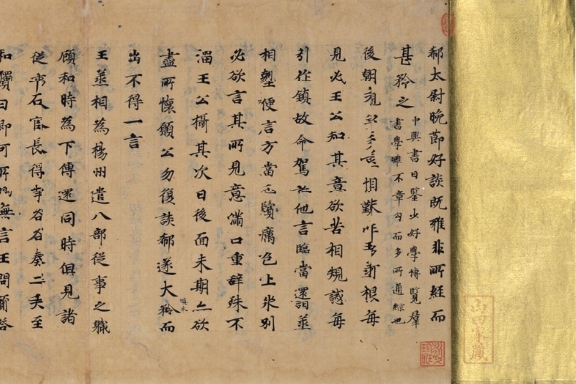

This body of literature includes the famous Chinese literary work known as the Shishuo xinyu 世說新語 (conventionally translated as A New Account of Tales of the World, hereafter Shishuo), compiled by the Liu-Song 劉宋 (420–479) prince Liu Yiqing 劉義慶 (403–444) and his staff, as well as later imitations of the Shishuo in both China and Japan – a total of thirty-seven separate items in my collection. Together they are known as Shishuo ti 世說體 (the Shishuo genre).

My article explores this rich archive of literature, written in classical Chinese (also known as the literary Sinitic), from the following three viewpoints: First, it identifies divination as a coherent and enduring aspect of renlun jianshi 人倫鑑識 (judgment and recognition of human [character] types, more succinctly translated as “character appraisal”), a major Wei-Jin intellectual practice that recognized and evaluated human character types and socio-political situations. Second, it examines the profusion of divinatory methods over time (from the Wei-Jin to the late Qing) and across space (China and Japan) that appear in Shishuoti works, showing how they were configured and reconfigured under certain specific social, political, and intellectual circumstances. Third, taking an explicitly gender-focused approach, this article evaluates women’s roles in mantic practices and the significance of their participation in the divinatory traditions of China and Japan.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.