Abstract

Bruce Lee did not set out to be a hero; he wanted to be an actor, a human being of action. Basically, he wished to be somebody: a human being who genuinely expressed himself in the kinetic language of martial arts, and one who helped others, likewise, to express themselves. And yet, despite his untimely death in 1973 at the age of 32, Bruce Lee posthumously became an international hero, a person who exerted a profound influence on global culture, providing a transcultural model of what it means to be truly human. With his lightning-fast kicks, incredible physique, and almost universally-recognizable kung fu battle cry (“Whoooeeeaaaaah!!!”, variously spelled), Bruce Lee became not just somebody, but rather the body that transformed Asian and American cinema: martial arts, body expression, fitness, masculinity, race, class, and anticolonialism. Mette Hjort wrote that “The transnational is prompted by economic necessities but the overarching goal is to promote values other than the purely economic: the social value of community, belonging, and heritage…and the social value of solidarity in the case of affinitive and milieu-building transnationalism.”[1] Bruce Lee embodied those values and inspired millions around the world of all ages and ethnicities. He was, I would argue, not only the first truly transnational Asian man of his age, but also a fighter for our age.

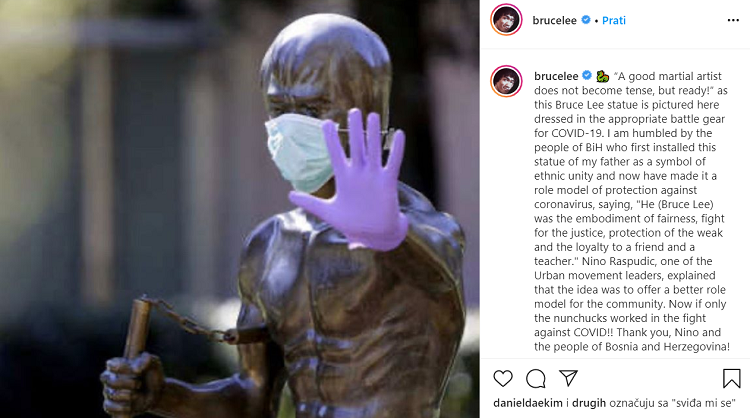

“We will always be Muslims, Serbs, or Croats. But one thing we all have in common is Bruce Lee,” said Veselin Gatalo of Urban Movement Mostar in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a country that was ravaged by civil war and the horrors of attempted genocide in the 1990s. Mostar was a city divided between Catholic Croats and Muslim Bosniaks. After hostilities ended, the people of Mostar chose to erect a peace memorial. Of the nominees, Bruce Lee was chosen even over the Pope and Gandhi, because polls revealed “he was the only person respected by both sides as a symbol of solidarity, justice, and racial harmony.”[2] It was the world’s first Bruce Lee statue. I include a photo of the bronze statue (Figure 1 below; screen-captured from Instagram, 8 April 2020), worth its weight in gold during the current coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic with its noticeable “upgrade,” a thoughtful reminder from the Mostar community that we are all in this together.

Those famous “nunchucks,” plainly visible in Bruce Lee’s right hand, while not exactly medical-grade “personal protective equipment” (PPE), might lift spirits enough to help just a little in fighting the pandemic! Joking aside, however, what does Bruce Lee have to do with coronavirus, cyberpunk, and our collective transnational future?

The year 2020 has been one of widespread economic disruption, sickness, and death. I need only briefly remind readers of the extent of the continuing disaster: in the United States alone, repeated lockdowns, businesses gutted, a peak of forty million jobless claims and a national unemployment rate exceeding fourteen percent, the highest since the Great Depression. At the time of writing (January 2020), American hospitals were overwhelmed, with over twenty-four million cases of infection and over 400,000 deaths having been reported. Globally, the infection toll had exceeded ninety million, while the death toll had passed two-million mark. As numbers continue to rise, the situation is grim. Although currently far less lethal in total mortality than the catastrophic influenza pandemic (commonly referred to as the ‘Spanish Flu’) of 1918-1920, almost exactly a century ago, the coronavirus pandemic has wreaked appalling damage worldwide.[3]

2020, a year that had been “sort of canceled,”[4] and certainly a year of heartbreak, outrage, suicide, street protests, and general despair in America, Asia, and the world, was one of great confusion, fear, hate-mongering, misinformation, and outright lies. The lights on Broadway are out; so are the lights of over 100,000 restaurants, small businesses, schools, and offices across the U.S. Amid this growing compendium of woe, the United States government, led by President Donald Trump, engaged in a trade war and a cyberwar with China, both sides taking actions and manipulating information in ways that have led to serious talk of a new Cold War. Most germane to this essay is the fact that U.S. President Donald Trump chose this moment of crisis to insult Bruce Lee, kung fu, the Chinese, and, by extension, Asian people generally, using much the same strain of mob-rousing racist, xenophobic rhetoric that historically infected America—you guessed it—exactly a century ago.

Calling COVID-19 the “China virus,” the “Chinese virus,” “Wuhan virus” and “kung flu,” Donald Trump loudly and repeatedly blamed China and the Chinese in thinly-disguised racial vitriol for crossing the Pacific bearing the coronavirus. At a political rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma (20 June 2020), he decided to make a “joke” about the deadly pandemic. The “Chinese virus” or coronavirus, he remarked, “has more names than any disease in history. … China sent us the plague . . . [and] I can name [it] ‘kung flu.’” Trump told the audience, “I can name 19 different versions of names,” and the crowd laughed appreciatively.[5] The Asian-American community immediately objected, but Trump uttered the phrase “kung flu” again in Phoenix, Arizona, while his supporters chanted the term as a sort of rallying cry.

Buzz Patterson, a Republican political candidate, supported Trump’s utterance with a shameless rhetorical question: “If ‘kung flu’ is racist, does that make Bruce Lee and ‘kung fu’ movies racist?” This provoked the ire of Bruce Lee’s daughter Shannon Lee, who retorted, “Saying ‘kung flu’ is in some ways similar to someone sticking their fingers in the corners of their eyes and pulling them out to represent an Asian person. It’s a joke at the expense of a culture and of people. It is very much a racist comment...in particular in the context of the times because it is making people unsafe.”[6] Coronavirus-fueled harassment and verbal/physical abuse of Asian-Americans, which were already rising in 2020, were repeatedly stoked by the racist pronouncements of President Trump and many of his followers.[7]

As early as February 2020, a man in New York City hit a woman wearing a face mask, “who appeared to be Asian,” calling her a “diseased bitch,” and in a Los Angeles subway during that same month, a man called the Chinese people “filthy,” claiming that “Every disease has . . . come from China because they’re f****** disgusting.”[8] In March 2020, a near-fatal hate crime took place in Texas, when a man stabbed members of an Asian family (including boys aged two and six, one of whom he wounded in the head) inside a Sam’s Club, believing the family to be Chinese and diseased “carriers” of the coronavirus. Dr. Kevin Nadal, who serves as a national trustee for the Filipino American National Historical Society, said of the incident, “The president’s insistence on referring to COVID-19 as the ‘Chinese Virus’ has emboldened anti-Asian bias. The increase in anti-Asian hate crimes is, without a doubt, a result of the racially charged rhetoric of COVID-19. Words matter.”[9]

A much-acclaimed new documentary on Bruce Lee called “Be Water” (official trailer) was created by Asian-American director Bao Nguyen, airing in June 2020 on the ESPN channel; it could hardly be timelier. Nguyen’s film argues that Bruce Lee is a protest figure whose life and words speak to us directly today in the age of Black Lives Matter—and other movements for racial justice, civil rights, and an end to police brutality—which have exploded onto the streets of America right before our eyes.[10] While the dominant narrative is that Bruce Lee was “this martial arts god, in many ways, and a film icon,” Nguyen stated that he “really wanted to see him through the lens of an immigrant American,” whose life stream coincided with the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s-1970s and the opening of China, and whose life was a constant protest against racism on both sides of the Pacific. “Bruce Lee is not seemingly the prototypical American,” Nguyen said, “But when you dive deeper . . . it’s very much the epitome of an American story.”[11] Nguyen holds that Bruce Lee’s legacy transcends borders, just as his life tied Hong Kong and America together across Pacific waters:

Even though Bruce Lee passed away nearly 50 years ago, his words continue to inspire action against oppression and injustice…protesters in Hong Kong are fighting for their way of life and black protesters in America are literally fighting for their lives—many having adapted Bruce’s ethos in their movement. As he said, “water can flow or it can crash,” and at this moment, our country seems to be crashing against a system and way of thinking that has for too long treated African-Americans as less than human—denying them justice, equity, and tragically, many times their own lives, like in the cases of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, among countless others.[12]Indeed, Bruce Lee’s life and legacy are prismatic lenses that allow us to reexamine our dynamic, transnational, and troubled times, sometimes in surprising ways. Perhaps most readers of this essay will not be martial artists, film buffs, or cyber-navigators; but Lee’s influence extends far beyond the fields of martial arts and so-called chop-socky films. As Paul Bowman wrote, “Bruce Lee has always been construed as a figure who existed at various crossroads—a kind of chiasmatic figure, into which much was condensed, and displaced. His films…have also been regarded as spanning the borders and bridging the gaps not only between East and West, but also between ‘trivial’ popular culture and ‘politicized’ cultural movements.”[13]

It is high time to reconsider the influence of Bruce Lee on our American collective culture (understood as a synthesis of transnational America and transnational Asia), and especially our street culture. Why? Because Black Lives Matter, and, as Lee recognized presciently, Asian lives and Asian culture can help make black and minority lives matter much more. Bruce Lee was literally––biologically and culturally––a transnational figure. His father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was a traditional Cantonese-opera singer, and his mother, Grace Ho, was the mixed-race descendant of a wealthy Eurasian family whose roots dated back to the history of British colonialism and foreign extraterritoriality. Bruce Lee’s lineage was one of migrants, among countless others in Hong Kong, a polyglot entrepôt of immigrant Chinese, British, Indian, and other peoples from across the British Empire.

Lee was born an American citizen in San Francisco, but his parents took him back to Hong Kong, where he was bullied for being a mixed-race “mongrel.” Thanks to his father, Lee had an early movie career as a child actor in Hong Kong cinema, and he was especially good at playing the part of the brash but charming orphan. However, Lee was a troublemaker and prankster who learned Wing Chun Kung Fu so that he could street-fight. When Lee’s Wing Chun classmates discovered that Lee’s mother was half-European and that he was not, therefore, “pure” Chinese, they shunned him.

In 1959, at the age of eighteen, Lee was kicked out of Hong Kong by his own parents after another bad street fight, and he took the slow boat to America with just $100 in his pocket. He worked as a dishwasher and waiter at Ruby Chow’s restaurant in San Francisco’s Chinatown, had his heart broken by his Chinatown-raised proto-feminist Japanese-American girlfriend Amy Sanbo, and became the first Chinese-American to openly break an unwritten Chinese taboo against teaching “non-Chinese” (in this case an Afro-American) the art of Chinese kung fu. He also dabbled in philosophy classes at the University of Washington, where he fell in love with, courted, and married a Caucasian woman, Linda Emery. (The early life of the young couple was dramatized in the Hollywood film Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story [1993], where, in a famous scene, Linda’s mother Mrs. Emery tells Bruce, “You’re an American citizen. You’re not really an American.”) Linda and Bruce had two children, Brandon and Shannon, before Bruce’s unfortunate death on 20 July 1973 in Hong Kong.

Bruce Lee’s race-breaking, no-nonsense attitude led him to teach Chinese Kung Fu to a Filipino-American (Dan Inosanto), a Japanese-American (Taky Kimura), an African-American (Jesse Glover), and many Caucasian-Americans, including boxer Joe Lewis and Hollywood stars such as Steve McQueen and James Coburn, and others. I mention Jesse Glover because when Bruce Lee died, his widow Linda brought his body back from Hong Kong to be buried in Seattle, the city where he had studied, lived, loved, and fought for respect. I once read to my students, and was also myself deeply moved by, the following line from Matthew Polly’s biography of Bruce Lee, which describes Lee’s private funeral: “As the crowd thinned and the mourners returned to their cars, the last person to remain was Jesse Glover. When the workmen came to fill the grave, Jesse took one of the shovels and shooed them away. It was a uniquely American moment—a black man in a suit with tears running down his face filling a Chinese grave in a white cemetery. Jesse says, ‘It didn’t seem right that Bruce should be covered by strange hands.’”[14]

There—I’ve condensed Bruce Lee’s eventful life into a few paragraphs. I offer now a thought piece on Bruce Lee in the time of coronavirus and cyberpunk. We are fighting both battles on- and off-line. We are becoming cybernetic in our work and learning (almost entirely-machine-based and remote due to the “physical distancing” exigencies of the coronavirus pandemic), and in our culture and communication as well, much of which is mediated by ubiquitous mobile devices, social media, and digital information. Donna Haraway famously argued in her 1991 feminist manifesto that the terms cyber and cyborgs empowered her to fashion an “ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism, and materialism,” which allowed her to reject the bright-line identity markers purporting to separate human from animal, and animal from machine, which are products of a “tradition of racist, male-dominant capitalism.” Haraway declared, “We are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.”[15]

Bruce Lee, if he were alive, would likely understand this kind of world, because he was a fighter with a thirst for novelty and knowledge but a deep aversion to mechanical crutches, shackles, and uncritical rules of form. We confront today a reality in which digital technology, automation, machine-learning, and artificial intelligence have intruded into every sector of our lives. In this essay, I suggest that we adapt Bruce Lee’s methodology and examine our own experiences in order to (as Lee once stated) “take what is useful, and develop [it] from there.”[16] Bruce Lee was a transnational, trans-Pacific, and kinetic human being who offers us lessons for studying our own flawed but fertile society—and hopefully mastering it through instinct, control, and compassion. We do not have to go to the extremes indicated in the epigraph above, choosing to be either “unscientific” or “mechanical” men and women who are no longer human beings. Let us, then, engage with Bruce Lee, a transnational fighter for our times.

[1] Mette Hjort, “On the Plurality of Cinematic Transnationalism,” in N. Durovicova & K. Newman, eds., World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives (London: Routledge, 2011), 12-33.

[2] Matthew Polly, Bruce Lee: A Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018), 493.

[3] South Asia specialist David Arnold has recently and importantly noted, however, that this seemingly compelling historical narrative—of “history repeating itself,” along with the expectation of catastrophic mortality in countries like India (where at least twelve million died during the previous century’s influenza pandemic)—is heavily colonial in nature, and must be critically tempered by what he calls an “insurgent” narrative, a careful stress on the specificity of postcolonial states like India in their politics and health systems, rather than easy comparisons with the past. David Arnold, “Pandemic India: Coronavirus and the Uses of History,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 79, No. 3 (August 2020): 569-577.

[4] Katherine Kam, “‘The Year Has Been Sort of Canceled,’” WebMD (Oct. 11, 2020).

[5] Mary Papenfuss, “Trump Uses Racist Terms ‘Kung Flu’ And ‘Chinese Virus’ To Describe COVID-19,” Huffington Post (22 June 2020).

[6] Kimmy Yam, “Bruce Lee's daughter on 'kung flu': 'My father fought against racism in his movies. Literally.’” NBC News (29 June 2020).

[7] For resources, news, and hate crime/abuse reports, see Stop AAPI Hate, and also the website of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, “Stop AAPI Hate”. Also see E. Tendayi Achiume, Felipe González Morales, Elizabeth Broderick, “Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance; the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants; and the Working Group on discrimination against women and girls,” Report to the U.N. Human Rights Council (12 August 2020).

[8] Holly Yan, Natasha Chen and Dushyant Naresh, “What's spreading faster than coronavirus in the US? Racist assaults and ignorant attacks against Asians,” CNN (21 Feb. 2020).

[9] Dorian Geiger, “Stabbing Of Asian-American Family At Texas Grocery Store Being Investigated As Coronavirus-Related Hate Crime,” Oxygen (3 April 2020).

[10] Jian Deleon, “Bruce Lee's Life Was a Form of Protest,” Highsnobiety, June 2020; Eric Francisco, “ESPN 30 For 30 Argues Bruce Lee was a ‘Protest’ Figure—and an ‘Asshole,’” Inverse, 3 June 2020. The “Be Water” documentary is available via streaming online on ESPN+ and Amazon Prime Video.

[11] Des Bieler, “Bruce Lee ‘30 for 30’ director says martial arts star is ‘the epitome of an American story,’” The Washington Post (Online), 7 June 2020.

[12] Bao Nguyen, “The Black Men Who Trained Bruce Lee for the Biggest Fight of His Life,” The Daily Beast (Newsweek), New York, 7 June 2020.

[13] Paul Bowman, “The Fantasy Corpus of Martial Arts, or, The ‘Communication’ of Bruce Lee,” Chapter 3 in Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World, eds. Douglas S. Farrer and John Whalen-Bridge (State University of New York Press, 2011), 64.

[14] Matthew Polly, Bruce Lee: A Life (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2018), 7.

[15] Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs

and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), 149-181. Also see Benjamin Wittes and Jane Chong, "Our Cyborg Future: Law and Policy Implications," The Brookings Institution, Sept. 2014.

[16] Bruce Lee, Tao of Jeet Kune Do (Santa Clarita, CA: Ohara Publications, 1975), dedication on inset page.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2020 Transnational Asia