Abstract

It was in the fall of 1990 that I began my journey as an anthropologist – firstly, of course, as a student. In the half-basement seminar room in Free School Lane, Cambridge, I remember presenting to my cohort class how I planned to approach Koreans in Japan, many among whom identified themselves as overseas nationals of North Korea despite not holding North Korean nationality. Most Koreans living in Japan in 1990 were immigrants from the period of Japan’s colonial rule of Korea between 1910 and 1945 and their descendants, and most of them originally came from the southern provinces of the Korean peninsula. An account of this odd state of affairs – Korea remaining divided into mutually antagonistic regimes after four and a half decades of what was supposed to be a temporary national partition, and Koreans in Japan remaining as disenfranchised non-citizens of Japan after multiple generations of Japan-born Koreans – had to be delivered to my classmates, one half of whom came from the United Kingdom and the other from outside the UK – mainly from the British Commonwealth nations of the South Asian subcontinent, Africa, and Australia. There were a few European students as well, but none from Korea or Japan.

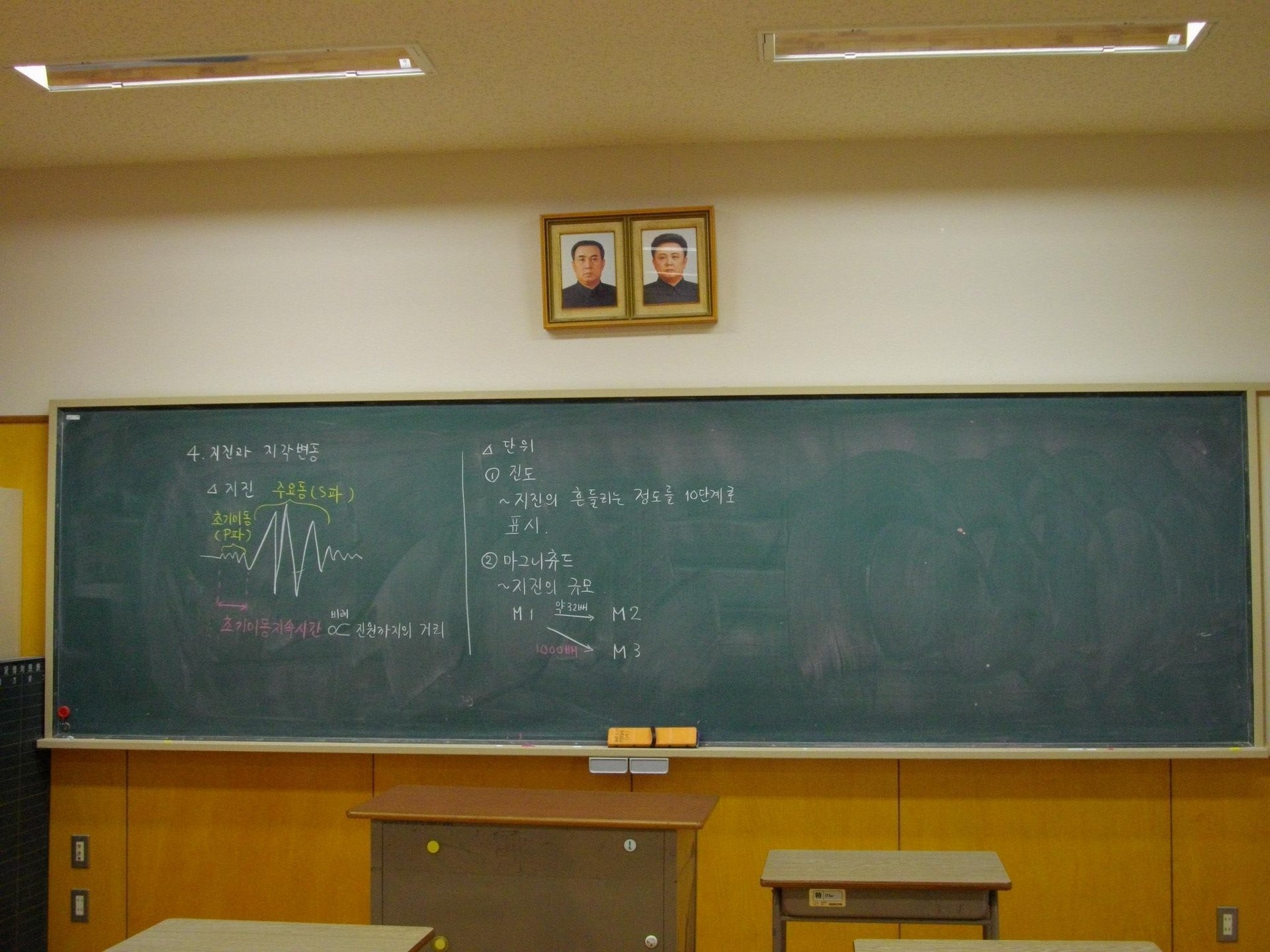

This class, euphemistically referred to as a “conversion” class, had been created for novice students like myself who had not studied anthropology as undergraduates, and had the objective of initiating us into the field of British Structural Functionalism, which was deemed an uncompromising doctrinal pillar of Social (not Cultural, as in the US) Anthropology. After one year’s study toward a Master of Philosophy, about half of us would continue to pursue PhDs there at Cambridge. My audience was international, multi-lingual, multi-cultural, and multi-racial, leading me to approach my topic with a strategy mixing political anthropology (one of the four modules we had to complete) with the anthropology of religion (another of the modules). My key ally in doing this was language: the fact that those Koreans in Japan learned the North Korean version of the Korean language in their independently-operated schools, despite their having been born in Japan and grown up using Japanese as their first language, was one of, if not the most important, pieces of ethnographic data that I was to rely upon. In this environment, children were exposed to formulaic language used to display reverence to the Great Leader Kim Il Sung and were taught to identify themselves as overseas citizens of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Most of these children would verbally identify themselves as “proud overseas citizens of the socialist fatherland.” Once outside the school, however, they would freely blend into the cultural norms of the Japanese society surrounding them, fully immersed in market trends, popular media products, and so on (see Ryang 1997). Being a student at a Korean school in Japan in the early 1990s meant acquiring two sets of behavioral conventions governed by two almost diametrically opposed, or more precisely speaking, mutually denigrating, norms and ideologies. At the forefront of such duality existed language, or rather, languages: the North Korean version of Korean, and Japanese, either the standard form or a regionalized one depending on where in Japan the student lived. These schools were operated by Chongryun, a Korean organization in Japan that holds North Korea to be the genuine homeland of Koreans in Japan and fashions its schools’ curricula after those of North Korea. The language of instruction was Korean and children attending the schools would become bilingual in Korean and Japanese. Yet, their bilingualism would be skewed toward greater proficiency in Japanese. This was because they were immersed in Japanese, their first language, when outside the school, including at home. Today, only an extreme minority of Korean children in Japan attend Chongryun schools, and even the teachers at these schools have a hard time using fluent Korean when instructing the children as they, too, grew up using Japanese as their first language.

Ever since the end of WWII, the Korean population in Japan has faced the following challenge: How to reconcile a desire to self-identify as Korean with a day-to-day existence in which the Korean language is absent. For example, immediately after the end of the war, Korean writers and intellectuals in Japan (self-)criticized the practice of writing in Japanese, the language of the colonizer, despite the fact that many of them were not able to write in Korean (Isogai 2015: 11). This tension derived from multiple sources. Due to national partition, compounded by the effects of Japanese nationality-related law, which remained colonial in nature vis-à-vis Koreans remaining in Japan for some time following the end of the war, Koreans in Japan faced uncertainty in relation to residential security and methods of legal identification. Due to the monocultural nature of the Japanese school system, which does not allow after-school programs for second or home languages, for example, the identity of Korean children attending Japanese schools (who are greater in number than those attending Chongryun schools) has never been given positive enforcement or healthy recognition – needless to say, this reflects deep-seated racial bias toward Koreans in Japanese society. In the case of individuals achieving positive self-identification as Korean after reaching adulthood, many lack the means to enact such an identity as, until recently, opportunities for learning the Korean language were limited (while ample opportunities were available for those interested in learning English, for example). Even in the case of Chongryun Koreans, as the proportion of Japan-born, younger-generation teachers at Chongryun schools continues to increase, Korean language education has become (for want of better word) superficial, with students exhibiting heavily Japanized accents, their speech displaying a (sometimes fascinating) mixing of Japanese and Korean languages. Moreover, for political reasons, Chongryun Koreans tend to skew toward North Korea in their language use, a tendency that is manifested in their choices of vocabulary and inflection, for example.

The practical as well as emotional hurdles to asserting and appropriating one’s Korean identity in Japan are captured in articles contained within this issue of Transnational Asia. Julia Hansell Clark examines a female Korean poet, Sō Shūgetsu, who lived in Osaka, Japan, the region of the country with the largest Korean population. Sō’s work, written in Japanese, yet unapologetically conveying the Korean woman’s struggle, is, interestingly, somewhat removed from the male-dominated diasporic discourse of nationalism and patriotism. Ran Wei’s article sheds light on the possibilities when comparatively reading a story by Yi Yangji, an award-winning female Korean writer in Japan, who, despite the fact that her family had been naturalized as Japanese, continued the difficult journey in search of her truthful self, and work by Nakagami Kenji, an award-winning Japanese writer of burakumin (outcaste) origin, whose story captures the intricate psyche of a Korean boy growing up in Japan in close proximity to a burakumin family. Finally, Shota Ogawa presents a critical reading of the recent multilingual and multi-vocal production of Pachinko (Apple tv, Hugh 2022) based on the eponymous original novel by Korean American writer Min Jin Lee (Lee 2007). Ogawa’s article indicates the global reach of the experience of Koreans in Japan, carefully delineating what is universally common in colonial and postcolonial immigrant life stories and what is uniquely solidified in the experience of Koreans in Japan. All of the articles touch upon, directly or indirectly, the issues of ethnic and host languages, the search for one’s true self, and resistance to multiple layers of power (be it colonialism, sexism, ethnic violence, social discrimination, and poverty) through the assertion of one’s own existence, life, and name. In the remainder of this Introduction, in order to frame these articles together, I shall present a short history of the emergence of what we now call zainichi Koreans as a conceptual object of inquiry in the current Anglophone academic discourse, before examining the term zainichi and the current situation faced by this group.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2023 Transnational Asia